In the Archives | Chicago’s Gay Academic Union

BY John D'Emilio ON March 13, 2017

At the University of Illinois at Chicago, where I taught for fifteen years, there is a Gender & Sexuality Center that provides services, meeting places, and programming for LGBT students; a Chancellor’s Committee on LGBTQ Concerns, which has access to upper-level administrators and makes recommendations about LGBT-related issues; many “out” faculty who do research on LGBT topics; a Gender and Women’s Studies program with courses related to LGBT history, culture, and experience; and an annual Lavender Graduation which is a joyous celebration of student success. UIC admittedly has a reputation as an especially LGBT-friendly campus. But its situation is not unique. LGBT people, issues, and research are very visible on college and university campuses across the United States.

Needless to say, this has not always been the case. A full history of how scholarly research, writing, and teaching developed and how a visible LGBT presence became institutionalized in U.S. higher education has not yet been written. But when that does finally happen, an important early piece of the history will be the story of the Gay Academic Union and the work it did in the 1970s and 1980s.

I was part of the small but steadily growing group that began meeting in New York early in 1973 and eventually formed the GAU. It served as an invaluable networking and support function at a time when most university faculty, graduate students, and staff were still in the closet and very little non-homophobic research was being done. I helped plan the first three national conferences, held in New York over Thanksgiving weekend in 1973, ’74, and ’75. Roughly three hundred people came to the first; by 1975, almost a thousand attended. (The proceedings of that first conference, and an account of how the GAU was formed, can be found here on the Outhistory site.

The Gerber/Hart Library and Archives has a number of collections related to the GAU in its Chicago incarnation – the papers of Randy Grisham, Stan Huntington, and James Manahan. They provide insight into the local workings of the organization and its national structure and activities as well. Reading through them, and especially the Grisham collection which has the most material, I came away with a clearer picture of both the extent of the national network that GAU sustained and the local workings of the Chicago chapter.

Above all, in the context of the 1970s when most LGBT individuals were not open about their identities, the national Gay Academic Union allowed local chapters to feel themselves part of a bigger network. A list of GAU chapters in 1979 included not just obvious places, like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, but also cities like St. Louis, Dallas, and Greensboro, North Carolina. The national GAU, which by the end of the 1970s was based in Los Angeles, maintained a mailing list of 6000, quite impressive for those times. It held national conferences that drew hundreds and allowed attendees to connect with people beyond their own city of residence.

The Chicago chapter formed in 1978. It held its first conference the following year, in May 1979. Only 50 people attended. But, when it organized a second conference in 1980, attendance jumped to 250. The conferences, as well as public lectures that it sponsored, allowed it to bring some of the authors of the first books on LGBT history, culture, and politics to Chicago. Speakers included James Steakley, who did pioneering research on the early gay movement in Germany; Lillian Faderman, whose Surpassing the Love of Men covered several hundred years of women’s intimate relationships with each other; and John Boswell, whose Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality was a publishing sensation when it appeared in 1980. These events gave visibility to the intellectual and cultural work being done as well as helped to build community locally.

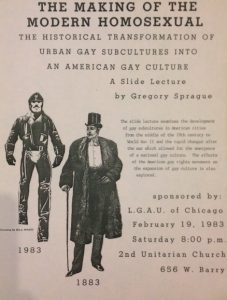

Besides functioning as something of a network node, GAU in Chicago also served as incubator for other projects. One of its members, Gregory Sprague, used GAU as a base from which to launch a Chicago Gay and Lesbian History Project. Sprague went on to do extensive research on Chicago’s pre-Stonewall LGBT history, going back to the early 20th century. He put together an illustrated slide lecture [this was before the days of PowerPoint presentations!] that he not only gave many times to audiences in Chicago, but that he also traveled with. Sprague was also a key player helping to organize historians within the American Historical Association.

Another project that GAU helped launch was a community-based library. It began collecting a wide range of books, both fiction and non-fiction, on LGBT topics. By November 1981 when the library opened as an independent organization at 3245 Sheffield Road, it was named – you guessed it – the Gerber/Hart Library and had a collection of over a thousand books.

Grisham’s papers also reveal the increasing difficulties GAU faced as a national organization. The national seemed to be in trouble as early as 1981, and by 1985 it dissolved, taking many of its local chapters down with it. The material at Gerber/Hart, including in the Huntington and Manahan collections, do not make it absolutely clear why this happened. But my sense, as I read through the materials, is that it was undone by its own successes. As GAU created a safe environment for LGBT faculty in higher education to meet and discuss issues, it made it more likely that these individuals would begin networking and organizing within their own professional associations – with other historians, anthropologists, sociologists, literary scholars, etc.

As a closing note: I’ve suggested in some of the earlier blog posts that one of the great joys of doing archival research is coming upon the unexpected pleasure – not so much something that changes my interpretation of the past, but that brings a big smile to my face. Well, there was one in Grisham’s papers. At the national GAU conference in 1982 that the Chicago chapter hosted at the Conrad Hilton Hotel, the high-profile gay journalist Randy Shilts was one of the plenary session speakers. He was described as delivering a “rambling” address, during which he happened to mention that he had just smoked a marijuana joint.

Comments