In the Archives | A Lesbian Community Center in Chicago

BY John D'Emilio ON July 14, 2017

Sometimes an archival collection can be the centerpiece of a research project. The papers of an individual will serve as the heart of a biography. The history of a key activist group can be reconstructed through the records of an organization. Major events or projects, such as a March on Washington or the Names Project Quilt, can be brought to life through the materials in a core set of papers.

Sometimes an archival collection can be the centerpiece of a research project. The papers of an individual will serve as the heart of a biography. The history of a key activist group can be reconstructed through the records of an organization. Major events or projects, such as a March on Washington or the Names Project Quilt, can be brought to life through the materials in a core set of papers.

More often, an archival collection is likely to be but one element in a larger, more ambitious project. Such was my reaction to exploring the materials in the papers of the Lesbian Community Center that are on deposit at the Gerber/Hart Library in Chicago. A two-box collection, it covers the period from 1980-83.

“Community Centers” have become a staple of LGBT life in larger cities. Today, they typically have paid staff and a large board of directors. They have a significant donor base and apply for government funds and foundation grants. They provide a range of services to youth, elders, and other groups within the LGBT population. The Centers serve as a dependable meeting place for other community organizations and they are a site for major community events. They may be located in buildings with a large array of offices and meeting spaces. They may have budgets in the millions of dollars, and they are likely to be open during the day and the evening, and during the week and on weekends.

Needless to say, this wasn’t always so. Chicago’s earliest community center, created by the Chicago Gay Alliance in 1971, occupied rental space in a house. The organization brought a lot of enthusiasm to the project, but with few financial resources and dependent entirely on volunteer labor, the Center barely lasted a handful of years before it had to close its doors.

Most of these early efforts at establishing community centers were dominated by men, not only numerically, but also in the sense of the kind of activities and interests that the centers supported. In many cities, open conflict developed over the effort of lesbians to have the space be welcoming to them as well. Los Angeles was one of the cities where, in the 1970s, these tensions erupted openly into bitterly fought battles.

In some cities, lesbians attempted to form their own community centers. But the challenges in the 1970s and early 1980s were even greater than those faced by the efforts led by gay men. The deeply structural gender bias in employment and wages made it harder for women who were attracted to women to live as a lesbian. Those who were out were likely to have fewer economic resources to sustain a community center. And, in this era, many lesbians had a primary commitment to a broader feminist activism.

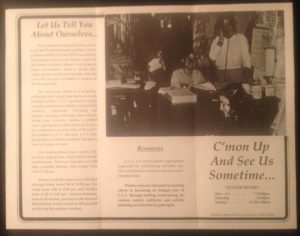

A Lesbian Community Center opened in Chicago in 1979. Located on Sheffield Avenue in Lakeview not far from Wrigley Field, it occupied two rooms on the second floor of a larger building. It maintained evening hours during the week and afternoon hours on Saturday and Sunday, a significant achievement. The Center maintained a lending library at a time when LGBT books were not so easily available. Describing itself as “a referral-information service and drop-in space,” it promised conversation, rap groups, and a wealth of information about resources available to lesbians in particular and women more generally. It also made its space available to other lesbian groups and organized cultural and athletic events.

For those interested in writing a history of the organization, the papers will prove disappointing. There just isn’t enough information to make the Center and its activities come alive. But – and here’s the good news! – for someone wanting to reconstruct a history of lesbian life in Chicago in this era in its social, cultural, and political dimensions, there is material that will prove invaluable. For instance, there is a binder in the collection marked “Resources, A to Z” and dated January 1, 1982. It contains the names of individual organizations as well as organizations grouped by categories ranging from “Bars” to “Third World Women’s Resources.” Imagine how useful that would be for tracing the contours of lesbian community and activism!

There are also three boxes of 3×5 index cards. One is a “Library Users File” with names and addresses. Another is a file of cards of volunteers with their names, what they are able to do and when they are available, and often with addresses as well. And there is a “Library Circulation File” in which each card lists a book and its author, and who has borrowed the book. As I flipped through all these cards, I could readily imagine a researcher constructing a master file of addresses designed to identify residential areas where lesbians were concentrated. The library circulation records would provide insight into the books that were most popular among lesbians in this period. Profiles of activists might emerge in the course of this close examination.

Finally, as almost always seems to be true in my archival explorations at Gerber/Hart, one odd and unexpected item stood out: a set of reel-to- reel tapes from the 1960s labeled “Dr. Goldiamond lectures – Washington School of Psych.” What might these contain, I wondered? Alas, without a reel-to- reel tape recorder, I wasn’t able to answer my question. But they are there for someone who has the interest and the diligence to find out.

Comments