Posts by Chris Gioia

Chris Gioia is currently enrolled at SUNY Empire State College in the Master of Arts in Liberal Studies program focusing on public history. Chris studied fine art and art history at School of the Art Institute of Chicago and has worked for Museum of the Moving Image and Museum of the City of New York in visitor services and retail operations.

Looking back and Listening: Memories of Stonewall

BY Chris Gioia ON June 27, 2017

“Sheridan Square this weekend looked like something from a William Burroughs novel as the sudden specter of ‘gay power’ erected its brazen head and spat out a fairy tale the likes of which the area has never seen.” [1] This is how Lucian Truscott IV rather disparagingly characterized the Stonewall rebellion of 1969 in his eyewitness account published in the Village Voice on July 2nd of that year. The event was indeed something never before seen in New York City’s West Village, but was not the first time LGBT people stood up to police harassment. The Black Cat Tavern raid in Los Angeles and the Compton’s Cafeteria riots in San Francisco a few years prior also saw members of the community fight back against unfair treatment, police brutality and discriminatory laws that targeted the most unambiguous members of the community.

Its hard to imagine that in New York City in 1969, laws prohibited members of the same sex dancing together, restricted the sale of alcohol to homosexuals and penalized those who wore articles of clothing of the opposite sex, but it would take years of activism and action to have these officially taken off the books in the following decades. So, how did the Stonewall Inn become the birthplace of LGBT civil rights? Many details are hard to nail down and many debates have focused on the myths and mysteries of the Stonewall incident, but specific memories and stories help to paint a picture of the place and of the times. Bars like the Stonewall Inn represented a kind of reluctant haven for New York City’s downtown gay scene. Most patrons had a love hate relationship with the bar and its mafia controlled operators. The drinks were weak and over priced, the ambiance was dive bar but the vibe was by most accounts intoxicating if not fully liberating.

Bruce Monroe, who was a college student visiting from Indiana in 1969, describes his memory of Stonewall to me:

I remember … two dance floors and a big long wall down the middle. But I remember it being a very young lively crowd that I could relate to. It was like really exciting to see all these other young men that were around my age. I guess it was one of the most popular places for dancing in NY at that- there weren’t very many places around like that. And I remember having a great time there and I remember having to leave by myself because my friends had found elsewhere to spend the evening.

Historian John D’Emilio’s experience of the West Village as a college student in the late 1960’s is of a “whole gay world.” On two occasions he visited the Stonewall Inn with a friend and remembers the following:

. . . so anyway we go to Stonewall and of course the thing that was immediately apparent to me I mean besides the fact that it was, unlike Julius’ where there were a lot of people but it was conversation, and it was kind of quiet, Stonewall was wildly noisy and what do they have, but go go boys who were dancing you know, up on a platform wearing you know, kinda nothing, like a g-string, or just underpants, and it seemed very exciting to see and experience something like that!

Author Felice Picano has written about Stonewall and been involved in gay literature/publishing since the 1970’s. He wasn’t a fan of Stonewall in 1969, but recalls that it could be useful:

. . . if you found somebody interesting and you sorta wanted to feel them up and feel them out before you took them home you’d take them around the corner to the Stonewall and slow dance in the dark and figure out what you wanted . . . it became by the time the incident happened, a place for trannies and for people who were not quite street people but almost, and sometimes the hustler boys who would hang out in front of it in the park in Sheridan Square would go in too. So it had this very, very mixed vibe and, and I was always hearing that it was closing down, that it was going bankrupt.

Trans activist Miss Majors introduces her story to Felice Picano in a rare correspondence:

Miss Majors: I’d had a tough day, and I heard that that singer Judy Garland had died. I wasn’t a fan of hers, but I didn’t feel like being alone, so I went down to the Stonewall. That was our club, where the other “T’s” and I could hang out and relax and be ourselves. [2]

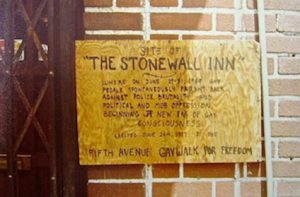

Stonewall Plaque placed in 1977 by the 5th Ave. Gay Walk of Freedom. LGBT Community Center Archives, Grillo Collection.

Pioneering gay journalist Mark Segal provides a first hand account of being inside the bar that night:

I remember the lights flashing. I remember asking somebody …“what does that mean?” And someone said, “Oh we’re just going to be raided!” And everybody who was a regular there took that very nonchalant. They were just used to it cause that was part of what life was like for gay people at that point. Me on the other hand had never been through a raid. I tried to look nonchalant but I gotta tell you its not –[laughs] I was very nervous. … As people were coming out they started forming a semi circle around the door and that eventually – and as the police let out more and more people at one point the only people left in the bar or most of the people left in the bar were the people that worked there and the police. At which point people just started throwing things at the door. Um, [sigh] that’s basically when people started breaking things, running up and down the street. [3]

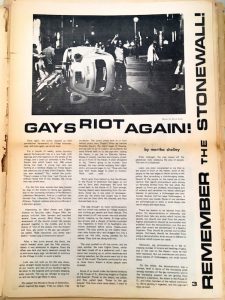

Activist Martha Shelly recalls in my interview with her last year, how the liberation movement was energized by Stonewall:

Monday I read about the riots in the newspaper and I thought that was what it was about! I read about the Stonewall Riot in some small article in the New York Times or the New York Post I don’t remember which and I immediately called . . . Jean Powers and she was the person who was getting out the newsletter and organizing meetings. I called her and said we have to have a protest march. She told me to call the head of the Mattachine Society and she said if they’re interested we could jointly sponsor it. …So I called Dick Leitsch who was the head of the Mattachine Society. He said they were having a meeting at Town Hall to discuss all of these things and what it meant for the gay community and come to the meeting and put my proposal out and that’s what I did.

Craig Rodwell, owner of the Oscar Wilde Memorial bookshop on Mercer St. at the time of the riot, sums up the significance of Stonewall:

Immediately I saw that this was something that was going to have an impact in the future for the movement because I’d been saying for years that something would happen- there would be a spark. I recognized instantly that this was it.[4]

Today the Stonewall Inn is an iconic symbol of the birth of LGBT rights and has secured its place in history by being designated a National Monument. To learn more about the liberation movement and hear more of the interviews I conducted visit www.stonewallhistory.us and for additional first hand testimony about Stonewall listen to a wonderful radio segment from 1989 here: Remembering Stonewall

At a performance upstairs at the Stonewall Inn not too long ago, I was shoulder to shoulder with a truly diverse mix of patrons: trans women and men, lesbians, drag queens, regulars who call the bar a hangout, more than a few allies, and of course tourists checking another landmark off their list. I like to think that the pioneers of the liberation movement who have passed, would be proud of what the reincarnated Stonewall represents, but I’m sure if asked a contentious debate would ensue. After all, if its not worth arguing about, was it worth fighting for?

Gay Power!

[1] Lucian Truscott IV, “Gay Power Comes to Sheridan Square,” Village Voice, July 2, 1969, accessed December 10, 2016, http://www.villagevoice.com/news/stonewall-gay-power-comes-to-sheridan-square-6670443.

[2] Felice Picano, “The Remains of the Night: Six Observers: Felice Picano Talks with Eyewitnesses to the Stonewall Riots,” The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, 2015 (4): 29.

[3] Mark Segal, interview by Christopher L. Gioia, February 7, 2017, interview.

[4] Tina Crosby, “The Stonewall Riot Remembered, Excerpt 2,” Stonewall: Riot, Rebellion, Activism and Identity, accessed April 14, 2017, https://stonewallhistory.omeka.net/items/show/25.

Stonewall: Riot, Rebellion, Activism and Identity

BY Chris Gioia ON April 24, 2017

My objective in creating stonewallhistory.us has been to collect a range of documents, images, texts and testimony about the controversial and crucial Stonewall rebellion. Presenting these items in an online digital database provides an entry point into the complex, tangled, web of stories and memories that construct the Stonewall narrative. Through this engagement with the past, the audience can determine for themselves if answers to the many questions that remain are possible – or even desirable. The accepted Stonewall narrative is that the riots are the spark that ignited the LGBT rights movement. For the most part, the community has embraced this view. Although the collective understanding that Stonewall is significant is not debated, on most other aspects agreement is hard to find: Which segment of the community led the way organizing protest? Did gay male social networks have a profound effect on organizing in the gay rights movement? Was the early homophile movement influential, or even considered by the more radical movement that emerged post-Stonewall? Were trans individuals influential in gay liberation? Were people of color invited to participate in activism? Who was really there that night in June of 1969? Who started the rebellion?

The facts and details of the rebellion are open for interpretation and in my opinion should remain so, for as this project hopes to demonstrate, Stonewall and the resulting birth of the “gay revolution” were very much spontaneous and creative. Barbie Zelizer writes in Remembering to Forget (a study of the impact of images of the Holocaust on collective memory) “…we allow collective memories to fabricate, rearrange, elaborate and omit details about the past, pushing aside accuracy and authenticity so as to accommodate broader issues of identity formation, power and authority, and political affiliation.”[1] Zelizer’s thesis, which could also be considered a warning, helped me to recognize that even the stories that emanate from those with the least power, who exist on the margins of society, are impacted by political and social influences. In the case of the Stonewall narrative the broader social movements of the time, the militant protest culture, the youth-oriented counterculture and consciousness raising all converged to help leaders of the nascent gay rights movement form a concept of identity, affiliation, and authority for the community. In this case, the authority that was exerted was the concept of oppression. Prior to Stonewall, many gays and lesbians existed quietly in the closet but enjoyed a moderate level of comfort and stability within their social lives and to a degree in society at large as long as they were reserved and respectable. The new authority, exercised by the liberation movement, was one that asked for more than tolerance and required acceptance.

I decided early on that recording oral histories would be a crucial part of this public history project. Alessandro Portelli’s examination of the history of the labor movement in Italy through oral histories was an inspiration for this decision. I found some similarities in the blurring of facts and chronology between the story of Stonewall and the narrative he chronicles in The Death of Luigi Trastulli and Other Stories. Nan Alamilla-Boyd notes that when writing his book, Gay New York George Chauncey states, “early in my research it became clear that oral histories would be the single most important source of evidence concerning the internal workings of the gay world.”[2] In my interviews I too became keenly aware of the hierarchies present within gay social circles. The power of listening to the recorded voices of my informants, elder members of the community, provides a uniquely accessible point of entry for those who may not be familiar with the events described. The crucial next step now that the site is built, the data collected and content written, is to disseminate it. Hearing the voices of older members of the community is something that can draw a listener into the rich history of the liberation movement. Alamilla-Boyd talks about the voices heard in oral histories as texts “…open to interpretation and their disclosures should be understood as part of a larger process of reiteration.” She questions whether factual details matter or whether a more romantic story is told through oral history.[3] Certainly the Stonewall story is romanticized as any other “battle” or “revolution” has been throughout history. But for some, it was perceived as a tool in a broader series of actions and reactions. The activist community in New York was clearly media savvy and therefore capitalized on the attention the unrest attracted, even the most disparaging. If it were not for the media coverage and the ensuing controversies, the commemorative potential of Stonewall may not have been realized.

The individual interpretations of participants, witnesses, activists, and authors also provide the means to shape the factors that contributed to Stonewall’s “success” as a catalyst and create a narrative that resonates beyond simple facts and a linear sequence of events. The development of this schematic narrative is echoed in the testimony of those I interviewed and also in the earliest written accounts such as the Rat Subterranean News coverage of the incident: “Soon pandemonium broke loose. Cans, bottles, rocks, trash cans, finally a parking meter crashed the windows and door,” the Rat reporter, known only as “Tom” writes. He concludes, “What was and should have always been theirs, what should have been the free control of the people was dramatized, shown up for what it really was: an instrument of power and exploitation. It was theater, totally spontaneous. There was no bullshit.”[4]

The development of this story into the schematic narrative of Stonewall is set in motion by the grassroots organizing that develops almost immediately after the first night of the rebellion. The narrative that develops represents elements that are derived from the protest movement culture of the late sixties and is tied to notions of identity that envelop the specific narrative (individual components that are arranged and interpreted schematically). [5] Craig Rodwell, Jim Fouratt, Martha Shelley as well as Sylvia Rivera can be seen as shaping this narrative of Stonewall Rebellion, while Dick Leitsch, Vito Russo and others authorize its re-telling. Despite the fact that this was by no means the first violent protest against police harassment, the event is instilled with the significance of the activist’s interpretation within the context of broader social movements of the time.

I hope to continue building the collection of stories, images, and documents contained on Stonewallhistory.us with the goal of bringing in as many voices and interpretations of the past as possible. Contributions of digitized archival material or written testimony and comments are welcome and can be submitted through the “contribute an item” tab on the home page.

__________________________________________________________________

[1] Barbie Zelizer, Remebering to Forget, University of Chicago Press; 1998

[2] Nan Alamilla-Boyd. 2008. “Who is the Subject? Queer Theory Meets Oral History.” Journal of the History of Sexuality (2): 177

[3] Ibid.

[4] Unknown, “The Rat, July 9-23, 1969, pg 6.,” Stonewall: Riot, Rebellion, Activism and Identity, accessed April 7, 2017, https://stonewallhistory.omeka.net/items/show/56.

[5] Knut Lundby. 2008. Digital Storytelling, Mediatized Stories: Self-Representations in New Media Peter Lang.