Posts by John D'Emilio

John D'Emilio has been researching and writing about the history of sexuality and social movements for forty years. His books include Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities, about the pre-Stonewall homophile movement, and Lost Prophet, a biography of Bayard Rustin. He recently retired from his teaching position at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

In the Archives | Running for Office

BY John D'Emilio ON August 21, 2017

Since Trump’s election, protest has become a way of life for many in the U.S. A week doesn’t pass without a flood of emails and posts on social media announcing the next march or rally in cities across the country. But his election also puts front and center the question of how electoral politics needs to figure among the playlist of strategies and tactics that movement activists for social and economic justice deploy. As Bayard Rustin argued in a 1965 appeal to activists in the black freedom struggle, ultimate success requires engagement with the electoral system.

Since Trump’s election, protest has become a way of life for many in the U.S. A week doesn’t pass without a flood of emails and posts on social media announcing the next march or rally in cities across the country. But his election also puts front and center the question of how electoral politics needs to figure among the playlist of strategies and tactics that movement activists for social and economic justice deploy. As Bayard Rustin argued in a 1965 appeal to activists in the black freedom struggle, ultimate success requires engagement with the electoral system.

For identity-based movements, one form that electoral involvement takes is running for public office. The first explicit LGBT electoral campaign that I’m aware of was in 1961 in San Francisco, when Jose Sarria, a well-known and well-loved drag performer at one of the city’s popular bars, ran for the Board of Supervisors in response to intense police harassment of LGBT people. But Sarria’s campaign was an isolated one-of-a-kind effort. Not until the rise of a gay and lesbian liberation movement in the 1970s did running for office become one of the recognized forms of movement activism. Yet, even then, it was still relatively uncommon.

Gary Nepon was the first “out” LGBT candidate to run in Chicago for public office. His papers at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives provide a view of how complex the relationship between a movement and electoral politics can be. In the fall of 1977, Nepon began putting a campaign together to win a place on the ballot as a candidate for the Illinois state assembly from the 13th district on Chicago’s northside lakefront. The district was already in the process of becoming identified as a center of LGBT (or “gay,” as the press referred to it then) life in Chicago.

Interestingly, though there had been a continuous history of organized LGBT activism in Chicago at least since the mid-1960s, Nepon was completely unknown among movement participants. As he admitted to the press in the first round of interviews after he announced his candidacy in October, “I am not a gay activist.” But Anita Bryant’s successful campaign to repeal a gay rights law in Dade County, Florida a few months earlier “hit me like a brick,” according to his Statement of Candidacy. Nepon felt he could no longer remain silent about gay issues, and so he decided to run for public office. He made clear that he was not a “single-issue” candidate. He stood for full access to abortion, including state funding for low-income women; no-fault divorce law; increased funding of public schools; and an expansion of state-supported children and family services. But his identity as a gay man was something that he was choosing to wear openly and proudly, even if he was not emphasizing LGBT issues in the campaign.

Interestingly, though there had been a continuous history of organized LGBT activism in Chicago at least since the mid-1960s, Nepon was completely unknown among movement participants. As he admitted to the press in the first round of interviews after he announced his candidacy in October, “I am not a gay activist.” But Anita Bryant’s successful campaign to repeal a gay rights law in Dade County, Florida a few months earlier “hit me like a brick,” according to his Statement of Candidacy. Nepon felt he could no longer remain silent about gay issues, and so he decided to run for public office. He made clear that he was not a “single-issue” candidate. He stood for full access to abortion, including state funding for low-income women; no-fault divorce law; increased funding of public schools; and an expansion of state-supported children and family services. But his identity as a gay man was something that he was choosing to wear openly and proudly, even if he was not emphasizing LGBT issues in the campaign.

One might assume that the LGBT community in Chicago would have jumped at the chance to rally behind one of its own. But nothing could be further from the truth. Nepon received virtually no endorsements of consequence from the LGBT community. Chuck Renslow, a gay entrepreneur and activist who was a precinct captain on the northside, did not support him. Gay Life, the main community newspaper, did not endorse him. In the view of Grant Ford, its publisher and editor, “the incumbents are our friends.” Nepon was running against incumbents [note: at this time, Illinois had districts that elected multiple candidates to the assembly] who had already shown their support for the community, according to Ford. He was wrong in assuming, as Renslow expressed it, that “the community will vote for him just because he’s gay.” When the votes were counted, Ford and Renslow were proven right. Nepon placed a distant last among the four candidates and, post-primary, was never heard from again in the world of Chicago LGBT activism.

So, what should we make of all this? Was his candidacy of no consequence? Was it nothing but a quirky oddity, a momentary distraction from the growing movement activism of the 1970s? The materials in the Nepon papers suggest otherwise.

What the campaign unquestionably produced was a level of press attention in Chicago that the LGBT movement did not yet commonly receive. The mainstream press seemed fascinated by Chicago’s “first avowed gay candidate,” as more than one newspaper described him. When San Francisco’s Harvey Milk, perhaps the LGBT political celebrity of the era, came to Chicago in a show of support for Nepon, it provided another excuse for journalists to report on what was otherwise a lackluster campaign. The Chicago Reader, a politically progressive weekly that was widely read, started their article about him, which ran for several pages, on its front cover. The headline read “Is Nepon the Great Gay Hope of Chicago?”

As it turned out, he wasn’t. But The Reader closed with a comment that does capture one way in which this was an important moment. “If the Nepon candidacy accomplishes nothing else, it has, for the movement at least, produced a new political phenomenon in Chicago: political candidates battling with each other to be the biggest friend of the gay community.” Sometimes, even a defeat can be a victory.

In the Archives | A Lesbian Community Center in Chicago

BY John D'Emilio ON July 14, 2017

Sometimes an archival collection can be the centerpiece of a research project. The papers of an individual will serve as the heart of a biography. The history of a key activist group can be reconstructed through the records of an organization. Major events or projects, such as a March on Washington or the Names Project Quilt, can be brought to life through the materials in a core set of papers.

Sometimes an archival collection can be the centerpiece of a research project. The papers of an individual will serve as the heart of a biography. The history of a key activist group can be reconstructed through the records of an organization. Major events or projects, such as a March on Washington or the Names Project Quilt, can be brought to life through the materials in a core set of papers.

More often, an archival collection is likely to be but one element in a larger, more ambitious project. Such was my reaction to exploring the materials in the papers of the Lesbian Community Center that are on deposit at the Gerber/Hart Library in Chicago. A two-box collection, it covers the period from 1980-83.

“Community Centers” have become a staple of LGBT life in larger cities. Today, they typically have paid staff and a large board of directors. They have a significant donor base and apply for government funds and foundation grants. They provide a range of services to youth, elders, and other groups within the LGBT population. The Centers serve as a dependable meeting place for other community organizations and they are a site for major community events. They may be located in buildings with a large array of offices and meeting spaces. They may have budgets in the millions of dollars, and they are likely to be open during the day and the evening, and during the week and on weekends.

Needless to say, this wasn’t always so. Chicago’s earliest community center, created by the Chicago Gay Alliance in 1971, occupied rental space in a house. The organization brought a lot of enthusiasm to the project, but with few financial resources and dependent entirely on volunteer labor, the Center barely lasted a handful of years before it had to close its doors.

Most of these early efforts at establishing community centers were dominated by men, not only numerically, but also in the sense of the kind of activities and interests that the centers supported. In many cities, open conflict developed over the effort of lesbians to have the space be welcoming to them as well. Los Angeles was one of the cities where, in the 1970s, these tensions erupted openly into bitterly fought battles.

In some cities, lesbians attempted to form their own community centers. But the challenges in the 1970s and early 1980s were even greater than those faced by the efforts led by gay men. The deeply structural gender bias in employment and wages made it harder for women who were attracted to women to live as a lesbian. Those who were out were likely to have fewer economic resources to sustain a community center. And, in this era, many lesbians had a primary commitment to a broader feminist activism.

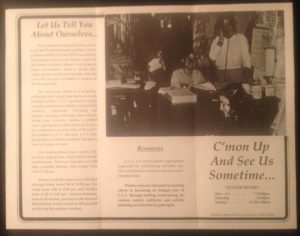

A Lesbian Community Center opened in Chicago in 1979. Located on Sheffield Avenue in Lakeview not far from Wrigley Field, it occupied two rooms on the second floor of a larger building. It maintained evening hours during the week and afternoon hours on Saturday and Sunday, a significant achievement. The Center maintained a lending library at a time when LGBT books were not so easily available. Describing itself as “a referral-information service and drop-in space,” it promised conversation, rap groups, and a wealth of information about resources available to lesbians in particular and women more generally. It also made its space available to other lesbian groups and organized cultural and athletic events.

For those interested in writing a history of the organization, the papers will prove disappointing. There just isn’t enough information to make the Center and its activities come alive. But – and here’s the good news! – for someone wanting to reconstruct a history of lesbian life in Chicago in this era in its social, cultural, and political dimensions, there is material that will prove invaluable. For instance, there is a binder in the collection marked “Resources, A to Z” and dated January 1, 1982. It contains the names of individual organizations as well as organizations grouped by categories ranging from “Bars” to “Third World Women’s Resources.” Imagine how useful that would be for tracing the contours of lesbian community and activism!

There are also three boxes of 3×5 index cards. One is a “Library Users File” with names and addresses. Another is a file of cards of volunteers with their names, what they are able to do and when they are available, and often with addresses as well. And there is a “Library Circulation File” in which each card lists a book and its author, and who has borrowed the book. As I flipped through all these cards, I could readily imagine a researcher constructing a master file of addresses designed to identify residential areas where lesbians were concentrated. The library circulation records would provide insight into the books that were most popular among lesbians in this period. Profiles of activists might emerge in the course of this close examination.

Finally, as almost always seems to be true in my archival explorations at Gerber/Hart, one odd and unexpected item stood out: a set of reel-to- reel tapes from the 1960s labeled “Dr. Goldiamond lectures – Washington School of Psych.” What might these contain, I wondered? Alas, without a reel-to- reel tape recorder, I wasn’t able to answer my question. But they are there for someone who has the interest and the diligence to find out.

In the Archives | Dignity

BY John D'Emilio ON June 23, 2017

James Bussen, 1988. Photo by Lisa Howe-Ebright

I have been thoroughly enjoying my explorations of collections at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives. Depending on the person or the organization, I come away with a deeper or a broader knowledge than I already had of topics in the history of LGBT life and activism since the 1960s. I love encountering the particular personal stories or the forgotten dramatic moments that emerge from individual documents in a collection and that are the stuff that makes history come alive. But, I also have to admit that, with my own history of activism and research, I haven’t found myself dramatically revising what I thought I knew.

Until now, that is. The collection I’ve explored most recently are the papers of James Bussen, a Chicago activist who, in the early 1970s, was a founder of the local Dignity chapter. He remained continuously active in the organization and later served as its national president in the second half of the 1980s. For those who don’t know, Dignity was for decades the primary organization giving voice to LGBT Catholics.

Before the 1960s, the Roman Catholic Church was like every other Christian community of faith. Homosexuality was a sin. Some denominations may have incorporated medical frameworks into their language, but there was little evidence of a significant move toward acceptance and approval. That began to change in the 1960s as some church activists and reformers began to speak out in support of gays and lesbians. This tendency accelerated significantly in the 1970s and 1980s. A number of religious denominations began to revisit official teachings on homosexuality and open themselves up to acceptance of LGBT members.

The Roman Catholic Church, however, stood out as moving distinctly against the grain. In October 1986, with the approval of Pope John Paul II, Cardinal Ratzinger issued a “Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Pastoral Care of Homosexuals.” It took a strong and uncompromising stand against any expression of homosexuality. The document described homosexual behavior as “an intrinsic moral evil” and a homosexual orientation as “an objective disorder.” In posing the question as to whether being a sexually active gay man was “a morally acceptable option,” it offered a categorically unambiguous answer: “It is not.” This 1986 document came to define Roman Catholicism as unremittingly and inflexibly homophobic. There seemed to be no possibility of change. And when Cardinal Ratzinger became Pope Benedict in 2005, it only confirmed this perspective.

After just a bit of reading through the material in the Bussen papers, however, it became abundantly – and surprisingly – clear to me that one of the effects of the 1986 Letter was to erase from my historical memory, and I suspect the memory of many others as well, a rich history of LGBT activism within the Catholic Church in the U.S. in the 1970s and early 1980s. At the simplest level, Dignity grew as an organization with impressive speed. Founded right at the beginning of the 1970s in the wake of the energy released by Stonewall and gay liberation, it expanded from seven chapters in 1973 to 70 by 1977 when it held its 3rd biennial convention in Chicago. 430 people registered for the national gathering of an organization that had grown to 4000 members. There were very few LGBT organizations of that size in the 1970s.

But it wasn’t only about size. Dignity projected a strong message of confidence and militancy. In its May 1973 newsletter, the editor wrote: “A force is growing within the Church. It will not be stopped.” At the end of the decade, the newsletter directed these words to its members: “it will not be theologians sitting in their offices who will one day decide that homosexuality makes sense . . . theologians will come around to thinking that only after a good number of gay people have already made sense of their own lives.” In other words, come out. Show your pride in how you live and what you do.

The Church, too, was responding in encouraging ways. In 1976, the Young Adult Ministry of the U.S. Catholic Conference issued a very positive statement about gay men and lesbians. At the local level, Dignity found itself in dialogue with a number of the more liberal Catholic bishops. Also in 1976, Dignity received an invitation to attend the “Call to Action” Conference of the Catholic Church in the U.S. The Conference passed the following resolution: “That the Church actively seek to serve the pastoral needs of those persons with a homosexual orientation; to root out those structures and attitudes which discriminate against homosexuals as persons; and to join the struggle by homosexual men and women for their basic constitutional rights to employment, housing, and immigration.”

The statement took me by surprise. It was far more positive than anything I might have imagined coming from the Catholic Church. It also provides context for the 1986 Letter of Cardinal Ratzinger. Rather than a simple articulation of the standard teachings of Catholicism, it represented an aggressive assault upon serious grassroots efforts that were stirring things up and provoking progressive change.

I came away from Jim Bussen’s papers with a very strong sense that there’s much to be learned by researching the history of Catholic LGBT activism and the Church’s response in the 1970s and 1980s. Bussen’s papers, other relevant collections at Gerber/Hart, and many that I’m certain exist in archives around the country will provide the materials. Without doubt, there’s a book waiting to be written. I hope someone seizes the opportunity – unless I beat you to it!

In the Archives | Artemis Singers

BY John D'Emilio ON June 7, 2017

As someone who is not particularly musical, thinking about the place of music and performance in history poses challenges. Certainly music has played an important role at various moments. No one would dispute, for instance, the importance of music in the civil rights movement and in white youth culture and protest in the 1960s. But, how does one evaluate its impact? How does it fit into the chronicle of a movement? How does it foster change in other spheres of society?

As someone who is not particularly musical, thinking about the place of music and performance in history poses challenges. Certainly music has played an important role at various moments. No one would dispute, for instance, the importance of music in the civil rights movement and in white youth culture and protest in the 1960s. But, how does one evaluate its impact? How does it fit into the chronicle of a movement? How does it foster change in other spheres of society?

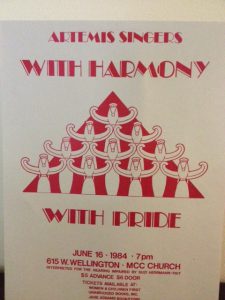

If you are interested in music and the place it deserves in writing history, then the papers of the Artemis Singers at the Gerber/Hart Library offer opportunities to explore this topic. Artemis was a self-consciously lesbian chorus. It saw itself as “an educational political vehicle for changing negative stereotypes about lesbians.” At the time when it formed in the summer of 1980, a world of women’s music was growing rapidly. Women’s music festivals were sprouting up around the country and there were at least a couple of dozen all women and openly feminist choral groups. Yet, as Susan Schleef, the founding director of Artemis, noted, among these groups in the early 1980s there was only one other self-declared lesbian chorus. Schleef and the members of Artemis intended to create more visibility for lesbians in this cultural environment, especially because music events across the United States were becoming public spaces of feminist solidarity. Artemis jumped right into this world, joining the recently founded Sister Singers Network, which kept these choruses in communication with each other and coordinated the planning of major events. Schleef and other Artemis members participated in the first Midwest Women’s Music Festival, held in the Ozarks in 1982, and helped make it into an annual event in the 1980s.

Besides its work in the thriving milieu of women’s music, Artemis also thrust itself into the newly emerging world of gay choral performance. In Chicago in 1979, two musical groups had formed, the Windy City Gay Chorus and the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Community Band, and they were beginning to perform at major events like the annual Pride March and Festival. An umbrella group, Toddlin’ Town Performing Arts, was created to provide nonprofit status and allow money to be raised to support the groups. Artemis became the third member of Toddlin’ Town and provided a lesbian presence at its meetings, where performances and other events were planned. At the time Artemis joined, the board of directors was entirely male and there was, in the words of one Artemis member, a “tendency towards mutual suspicion between lesbians and gay men.”

In 1983, the relatively young network of LGBT choral societies took a big leap forward into visibility. The first “National Gay Choral Festival” was scheduled for September, to be held in Manhattan at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, as prestigious a cultural venue as existed in the U.S. Almost 700 singers from 11 choruses performed at the Festival. Artemis was the only group of women. “Come Out and Sing Together,” as the festival was titled, stretched out over three days. At a time when AIDS was beginning to ravage the world of gay and bisexual men in large American cities, and when media coverage strengthened the most negative stereotypes of homosexuality, the choral festival provided a much-needed counterpoint. By 1986, when a second national choral festival was held, “women’s participation had increased five-fold,” according to a report in the Artemis Papers.

In 1983, the relatively young network of LGBT choral societies took a big leap forward into visibility. The first “National Gay Choral Festival” was scheduled for September, to be held in Manhattan at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, as prestigious a cultural venue as existed in the U.S. Almost 700 singers from 11 choruses performed at the Festival. Artemis was the only group of women. “Come Out and Sing Together,” as the festival was titled, stretched out over three days. At a time when AIDS was beginning to ravage the world of gay and bisexual men in large American cities, and when media coverage strengthened the most negative stereotypes of homosexuality, the choral festival provided a much-needed counterpoint. By 1986, when a second national choral festival was held, “women’s participation had increased five-fold,” according to a report in the Artemis Papers.

The work of Artemis, as well as that of other lesbian choruses that sprang up in these years, did have an impact on the gender dynamics of these musical networks. Testimonials from a national conference of GALA (the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses) held in Minneapolis in 1986 document the progress. “I went to Minneapolis with more than a slight case of negativity,” one lesbian wrote afterward. “I had prepared myself to grin and bear it . . . Never did I dream that I would come to feel such a close and compassionate bond with 1200 other singers, most of them men.” Another woman wrote, “while the membership and leadership are overwhelmingly male, most seem supportive or even enthusiastic about recruiting women’s choruses . . . Anything is possible.”

Besides the documentation that allows a researcher to construct the changing gender dynamics and composition of this musical world, the papers also are suggestive of the way that a group like Artemis helped build a sense of community and shared identity. Artemis Singers performed several times a year in Chicago. Sometimes the events were consciously political, as when they did a benefit concert to raise money for Gay Community News, a Boston-based LGBT weekly with very progressive politics. Sometimes the events were benefits to support Artemis, none of whose members were paid, but for whom the expense of traveling to festivals and purchasing music could be costly.

I’m not sure how one measures the impact of a group like Artemis. But, coming across comments like the concert was “a smashing success” or an event was filled with “magical moments” certainly suggests a collective power to the experience. It was not uncommon for 200- 300 people to attend these musical events in various community venues. One measure of the appeal of Artemis, perhaps, is the fact that in 2017, thirty-seven years after its founding, the Artemis Singers are still performing!

In the Archives | Black and White Men Together

BY John D'Emilio ON May 8, 2017

When historians do their research, many of us often operate with a set of categories that help to sort and divide the past into neatly organized separate boxes. There are histories of politics and movement activism; of social life and community; of culture and artistic production. But, alas, life is not always so neatly segmented. Political activism can be a force for building community. Socializing in bars sometimes became the setting for mobilizing people, most famously at the Stonewall Inn in 1969. And cultural creativity can help articulate political grievances and rouse people to action.

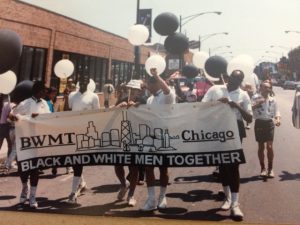

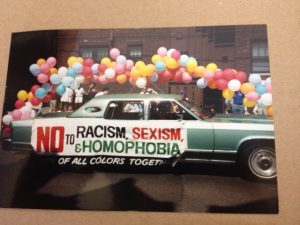

The haziness of history’s boundaries came home to me as I worked my way through two small, but related, collections at Gerber/Hart: the papers of Ken Allen and Wendell Reid. Their materials stretch across the 1980s and 1990s. Each of them was active in the Chicago chapter of Black and White Men Together (BWMT) which, in some cities, morphed over time into Men of All Colors Together.

Black and White Men Together formed in San Francisco in the spring of 1980. By the time it held its first conference in San Francisco during Pride Month in 1981, there already were ten chapters, stretching from cities in California to Arizona, Missouri, Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. Three hundred men attended that first national convention. By 1987, based on the holdings in these collections, at least 17 chapters were regularly producing newsletters, some of which were quite substantial. In 1991, on the 10th anniversary of its first convention, there were at least 25 chapters, including in cities not generally thought of as hubs of gay male life – among them, Hartford, Connecticut; Youngstown, Ohio; and Louisville, Kentucky.

From the outside, BWMT was often perceived as what today one might describe as a “meet-up” group for gay men whose sexual attractions crossed a color line. And, undoubtedly, it did serve that purpose, filling a need that was all the more pressing because evidence abounds that in the 1970s many gay bars implemented policies of excluding African American men by demanding extra pieces of identification. BWMT provided safe spaces for interracial socializing. That socializing in turn helped build broad social networks that facilitated organization building.

Even a quick look through the papers of Allen and Reid shows how strong the activist motivations were in BWMT. For instance, the programs of the 1991 and 1992 national conventions, held in Detroit and Dallas respectively, provide ample evidence of political consciousness and intentions. Keynote speakers included Perry Watkins, an African-American soldier who was challenging the military’s LGBT exclusion policy; Keith St. John, a member of the Albany, New York city council and the first openly gay black man elected to public office; Mandy Carter one of the most politically progressive grassroots community organizers in the U.S; and Marjorie Hill, the director of New York City’s Office for Lesbian and Gay Community Concerns. Many of the workshops at these conferences were unmistakably activist in their focus: “You Can’t Fight AIDS from the Closet”: “Lesbians and Gays of Color as a Political Force in the ’92 Elections”; “A History of Gay Rights”; and “Establishing Your Own HIV/AIDS Agency.”

This orientation toward movement activism also shows up at the local level. Box Six of Ken Allen’s papers is filled with newsletters from local chapters. Those from 1987 are overtly recruiting and encouraging readers to come to the 1987 March on Washington. Many newsletters were important sources of information on the growing AIDS epidemic, at a time when mainstream media coverage was still inadequate. The Los Angeles chapter successfully applied for a grant to engage in community-based AIDS education.

Of all the materials I found in these collections, the piece that most caught my attention and that serves as powerful evidence of the activist intentions of BWMT’s leadership was a 150-page publication, Resisting Racism: An Action Guide. It included outlines and resource materials for twenty different workshops intended to equip participants with tools and knowledge to counter racism. There was material from lesbian writers like Audre Lorde and Cherrie Moraga. There were articles on “Racism in the Movement” and “What Black History Month Should Mean to White Gays.”

Taken together, these collections provide a glimpse into the kind of organizing that was being done by gay men in the 1980s and 1990s to challenge racism both within and beyond the gay community in many cities across the U.S.

In the Archives | Chicago’s Gay Academic Union

BY John D'Emilio ON March 13, 2017

At the University of Illinois at Chicago, where I taught for fifteen years, there is a Gender & Sexuality Center that provides services, meeting places, and programming for LGBT students; a Chancellor’s Committee on LGBTQ Concerns, which has access to upper-level administrators and makes recommendations about LGBT-related issues; many “out” faculty who do research on LGBT topics; a Gender and Women’s Studies program with courses related to LGBT history, culture, and experience; and an annual Lavender Graduation which is a joyous celebration of student success. UIC admittedly has a reputation as an especially LGBT-friendly campus. But its situation is not unique. LGBT people, issues, and research are very visible on college and university campuses across the United States.

Needless to say, this has not always been the case. A full history of how scholarly research, writing, and teaching developed and how a visible LGBT presence became institutionalized in U.S. higher education has not yet been written. But when that does finally happen, an important early piece of the history will be the story of the Gay Academic Union and the work it did in the 1970s and 1980s.

I was part of the small but steadily growing group that began meeting in New York early in 1973 and eventually formed the GAU. It served as an invaluable networking and support function at a time when most university faculty, graduate students, and staff were still in the closet and very little non-homophobic research was being done. I helped plan the first three national conferences, held in New York over Thanksgiving weekend in 1973, ’74, and ’75. Roughly three hundred people came to the first; by 1975, almost a thousand attended. (The proceedings of that first conference, and an account of how the GAU was formed, can be found here on the Outhistory site.

The Gerber/Hart Library and Archives has a number of collections related to the GAU in its Chicago incarnation – the papers of Randy Grisham, Stan Huntington, and James Manahan. They provide insight into the local workings of the organization and its national structure and activities as well. Reading through them, and especially the Grisham collection which has the most material, I came away with a clearer picture of both the extent of the national network that GAU sustained and the local workings of the Chicago chapter.

Above all, in the context of the 1970s when most LGBT individuals were not open about their identities, the national Gay Academic Union allowed local chapters to feel themselves part of a bigger network. A list of GAU chapters in 1979 included not just obvious places, like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, but also cities like St. Louis, Dallas, and Greensboro, North Carolina. The national GAU, which by the end of the 1970s was based in Los Angeles, maintained a mailing list of 6000, quite impressive for those times. It held national conferences that drew hundreds and allowed attendees to connect with people beyond their own city of residence.

The Chicago chapter formed in 1978. It held its first conference the following year, in May 1979. Only 50 people attended. But, when it organized a second conference in 1980, attendance jumped to 250. The conferences, as well as public lectures that it sponsored, allowed it to bring some of the authors of the first books on LGBT history, culture, and politics to Chicago. Speakers included James Steakley, who did pioneering research on the early gay movement in Germany; Lillian Faderman, whose Surpassing the Love of Men covered several hundred years of women’s intimate relationships with each other; and John Boswell, whose Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality was a publishing sensation when it appeared in 1980. These events gave visibility to the intellectual and cultural work being done as well as helped to build community locally.

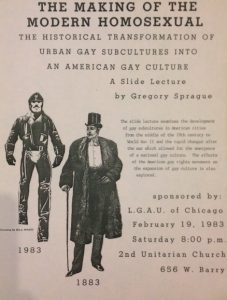

Besides functioning as something of a network node, GAU in Chicago also served as incubator for other projects. One of its members, Gregory Sprague, used GAU as a base from which to launch a Chicago Gay and Lesbian History Project. Sprague went on to do extensive research on Chicago’s pre-Stonewall LGBT history, going back to the early 20th century. He put together an illustrated slide lecture [this was before the days of PowerPoint presentations!] that he not only gave many times to audiences in Chicago, but that he also traveled with. Sprague was also a key player helping to organize historians within the American Historical Association.

Another project that GAU helped launch was a community-based library. It began collecting a wide range of books, both fiction and non-fiction, on LGBT topics. By November 1981 when the library opened as an independent organization at 3245 Sheffield Road, it was named – you guessed it – the Gerber/Hart Library and had a collection of over a thousand books.

Grisham’s papers also reveal the increasing difficulties GAU faced as a national organization. The national seemed to be in trouble as early as 1981, and by 1985 it dissolved, taking many of its local chapters down with it. The material at Gerber/Hart, including in the Huntington and Manahan collections, do not make it absolutely clear why this happened. But my sense, as I read through the materials, is that it was undone by its own successes. As GAU created a safe environment for LGBT faculty in higher education to meet and discuss issues, it made it more likely that these individuals would begin networking and organizing within their own professional associations – with other historians, anthropologists, sociologists, literary scholars, etc.

As a closing note: I’ve suggested in some of the earlier blog posts that one of the great joys of doing archival research is coming upon the unexpected pleasure – not so much something that changes my interpretation of the past, but that brings a big smile to my face. Well, there was one in Grisham’s papers. At the national GAU conference in 1982 that the Chicago chapter hosted at the Conrad Hilton Hotel, the high-profile gay journalist Randy Shilts was one of the plenary session speakers. He was described as delivering a “rambling” address, during which he happened to mention that he had just smoked a marijuana joint.

In the Archives | Gay Liberation

BY John D'Emilio ON February 7, 2017

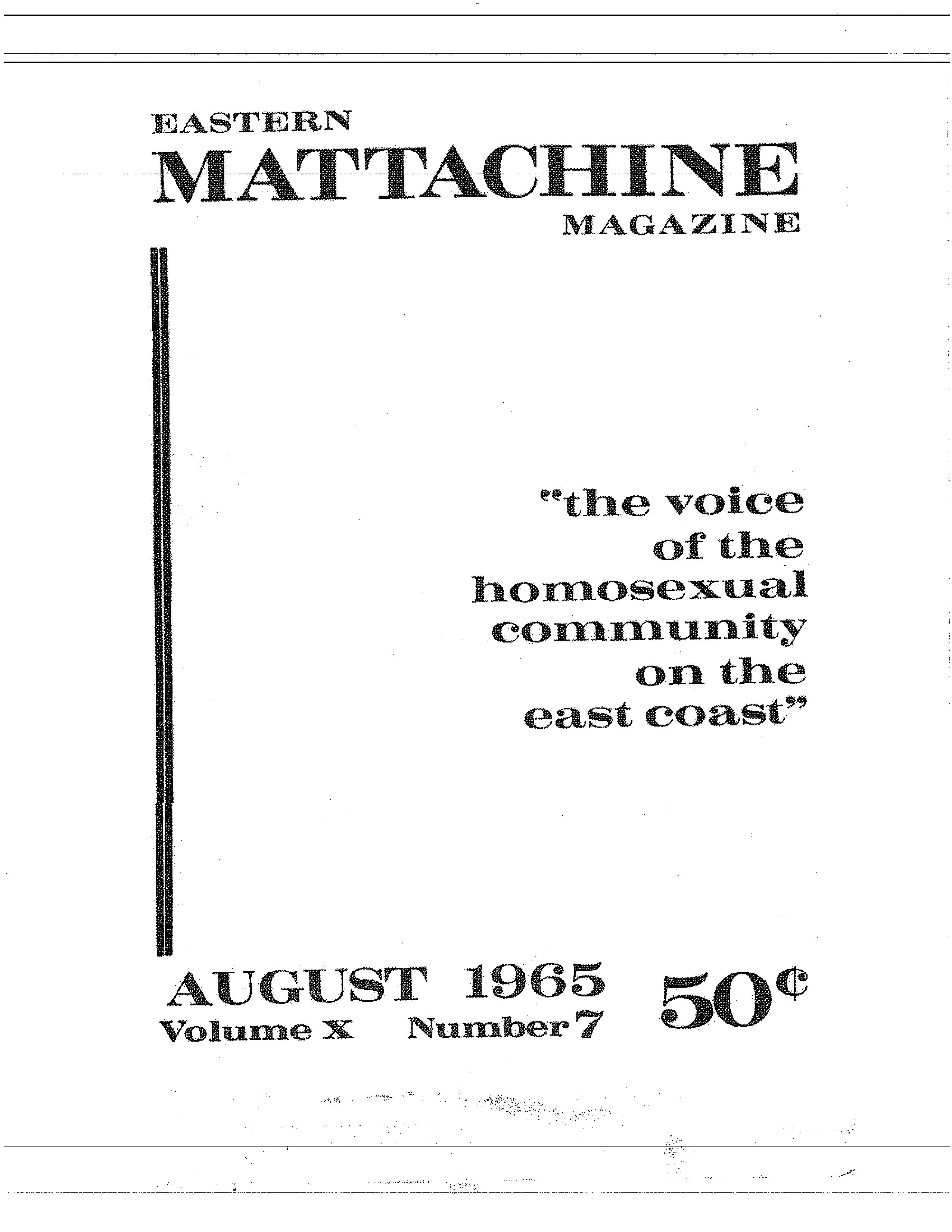

August 1965 Cover of Mattachine Magazine, from OutHistory.org

Besides the papers of individuals and organizations, an archive like the Gerber/Hart Library in Chicago also contains LGBT periodicals. This can be especially important when the periodicals are the newsletters of local organizations. Most of these did not have massive circulation or long runs. Yet they do often provide thorough and detailed reports on local events and the work of the organization. They also frequently contain opinion pieces and commentary written by local activists that give a vivid sense of the times.

Two such periodical collections are the newsletters of Chicago Gay Liberation and the Chicago Gay Alliance. These were two of the very earliest post-Stonewall organizations to form in Chicago, and the newsletters at Gerber/Hart stretch from 1970 to 1972. They report on the broad range of activities that the groups engaged in, the demonstrations they organized, and the tensions and challenges they each confronted.

At first glance, the story that unfolds in Chicago seems to parallel the narrative that historians have constructed of early post-Stonewall activism in New York. In the wake of Stonewall, a group calling itself the Gay Liberation Front quickly formed in New York. Self-declared militant revolutionaries, they conducted sassy public actions, urged people to come out, declared solidarity with other radical movements of the day, and displayed that solidarity by participating as openly queer contingents in marches against the Vietnam War and at rallies in support of the Black Panther Party. Within months, a group of white gay men split from the GLF and formed the Gay Activists Alliance. It, too, was committed to militant public action, but it broke with the multi-issue coalition politics of the Gay Liberation Front and declared itself solely focused on gay issues.

Reading the Chicago Gay Liberation Newsletter, one immediately encounters its multi-issue orientation. Besides organizing a Pride March and Rally in June 1970, and conducting demonstrations at restaurants that refused to serve gay customers, it also sent a contingent to participate in the march commemorating those who died in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and it organized support for the Venceremos Brigade, a group of young radicals who were supporting the Cuban revolution and defying the U.S. boycott of the island nation. One of its issues contained a report on the Revolutionary People’s Party Convention, held in Philadelphia in September 1970 and organized by the Black Panther Party. Chicago Gay Liberation included both a women’s caucus and a black caucus, which worked to keep issues of sexism and racism in the vision of the organization while also remaining active in the organization as a whole.

The October 1970 issue of the newsletter reports that Chicago Gay Liberation is experiencing a “schism.” A large group of white gay men decided to secede from the organization because it was “too political, too radical” and was “allying itself too closely to Movement groups.” They formed a new group, Chicago Gay Activists. The first issue of its newsletter, published in November 1970, announced that “our politics are that of homosexuality.” Another article declared that “the most important part of liberation is personal.” CGA definitely remained a militant organization. It planned and conducted public demonstrations that could be rowdy and disruptive. But it continued to proclaim that CGA “is devoted solely [emphasis in original] to the politics of homosexuality.”

Although this seems to mirror what had happened a few months earlier in New York, a closer reading of the newsletters leads to a more complicated and nuanced analysis. Chicago Gay Liberation, for instance, might declare itself a revolutionary organization, but a surprisingly large number of its demonstrations were focused on obtaining the right to dance. The famous retort by Emma Goldman notwithstanding (“If I can’t dance, it’s not my revolution”), one could reasonably argue that the right to dance was not the cutting edge of revolutionary change for LGBT people. Meanwhile, though CGA stated that its only focus was on homosexuality, its newsletter reported on gay contingents at antiwar marches, provided its readers with information about the Hiroshima Day rally, and joined in a broad coalition action to protest President Richard Nixon’s appearance in Chicago. At least in Chicago, the divide between revolutionary and reformist, between multi-issue and single-issue politics, was a good deal hazier than it might seem upon first analysis.

What I found most exciting about reading these newsletters was encountering the intensity and extent of activism in this three-year period. Especially when one considers that both organizations were run entirely on volunteer labor and had almost no budget to consider, the amount of work they did in the three years covered by these newsletters was huge. Between them, they organized protests against police harassment and violence. They demonstrated against gay bars that discriminated to keep women and people of color out, and against other commercial establishments that discriminated against LGBT people. They appeared on radio and TV shows, at a time when a visible queer presence was still extremely rare. They maintained a speakers bureau and sent speakers to high schools in the greater Chicago area. They polled candidates for Chicago’s city council, and they testified at city council hearings about the need to enact laws banning discrimination. They helped organize student groups on campuses around the state. CGA opened Chicago’s first community center for LGBT people, located in a house at 171 Elm Street. CGA maintained a mailing list of 1300, at a time when doing a hard-copy mailing was the main way to communicate to people en masse, and that involved a lot of work. CGA likewise produced 3,000 copies of its newsletter, and distributed it in many venues in the city.

Today, when so many LGBT organizations have paid staff, when many elected officials seek out LGBT endorsements, and when there is so much cultural visibility and attention by news media, it can be hard to appreciate just how cutting edge the work of these two early post-Stonewall organizations in Chicago was. It made a difference. It created a beginning foundation upon which later organizations and activists built. And the work of Chicago Gay Liberation and Chicago Gay Alliance comes down to us today in part because an archive like the Gerber/Hart Library contains precious copies of many of the newsletters of these organizations.

In the Archives | The Irwin Keller Papers: 1987 Sexual Orientation and the Law Conference

BY John D'Emilio ON January 9, 2017

To research and write about Chicago’s LGBT history is to engage in a form of what’s often described as “local” history, writing about a particular place within a larger nation. Yet local history also reaches beyond the place it describes. The “local” can be used to illustrate broader historical patterns and to make generalizations about an era or a topic. And, sometimes, a place like Chicago can be the setting for events that might be considered national in their reach and consequence.

To research and write about Chicago’s LGBT history is to engage in a form of what’s often described as “local” history, writing about a particular place within a larger nation. Yet local history also reaches beyond the place it describes. The “local” can be used to illustrate broader historical patterns and to make generalizations about an era or a topic. And, sometimes, a place like Chicago can be the setting for events that might be considered national in their reach and consequence.

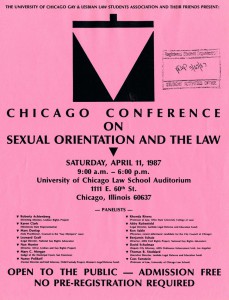

Such was the case in April 1987 when Chicago hosted a conference on “Sexual Orientation and the Law.” Held at the University of Chicago, it was organized by the Gay and Lesbian Law Students Association at the University. Twenty years later, Irwin Keller, who was one of the key organizers of the Conference and a student in the Law School, donated the papers related to the conference to the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives. The Keller Papers provide great insight into the state of the law in the mid-1980s and the strategic thinking of key LGBT legal activists.

Think about the moment. It was several years into the AIDS epidemic, with caseloads and deaths growing in number exponentially. The Reagan presidency was unrelentingly hostile to anything gay, completely ignored the AIDS crisis, and welcomed the religious right into the center of the Republican Party. And, as all this was going on, in June 1986 a 5-to-4 Supreme Court decision in the Bowers v. Hardwick case upheld the constitutionality of state sodomy laws. Bad as the decision waBowers v. Hardwick cases, the language used by the justices in the majority was hostile and derogatory. It described the claims made by those challenging the constitutionality of sodomy statutes as “facetious.” The laws, it said, were rooted in “millennia of moral teaching.” The Constitution offered “no such thing as a fundamental right to commit homosexual sodomy.”

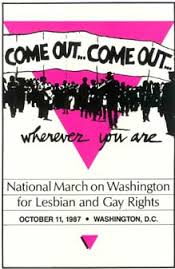

But sometimes defeats can have benefits. Hardwick was a spur to action. It helped to create the demand for a national March on Washington, scheduled for October 1987, a march that would prove to be a demonstration of staggeringly large numbers. And it provided the impetus for members of the Gay and Lesbian Law Students Association at the University of Chicago to propose and organize the first national conference on “Sexual Orientation and the Law,” scheduled for April 11, 1987.

Organizers of the conference cast a wide net. They sent mailings announcing the conference to every law school in the country, hoping not only to reach law students everywhere but also, perhaps, to spur LGBT law students to organize. Estimates of the number who attended the conference that day ranged from five to six hundred. The conference planners also sent invitations to participate to a broad range of legal activists and constitutional lawyers.

The list of those who spoke at the conference reads like a roll call of the pioneers in LGBT legal activism: Thomas Stoddard, Executive Director of Lambda Legal Defense, the first national LGBT legal organization, and Abby Rubenfeld, who was Lambda’s legal director; Nan Hunter, the founding director of the ACLU’s Lesbian and Gay Rights Project; Mary Dunlap, a lawyer who just a few weeks before had argued the “Gay Olympics” case before the Supreme Court and was awaiting the Court’s decision in the case; Roberta Achtenberg, the chief attorney for the National Lesbian Rights Project; and Nancy Polikoff, who had been an attorney for the Women’s Legal Defense Fund and helped cut a path for feminist and LGBT family law.

At times the tone of the sessions was somber. On the opening panel, Tom Stoddard commented on the impact of Hardwick. Looking back on some earlier lower court victories, he said that Hardwick “erases that progress in the federal courts to a very strong degree . . . [and] makes it harder to win on state issues as well.” Evaluating the state of immigration law as it related to lesbians and gays, another panelist frankly said “it is a mess.” Panelists debated whether it made more sense in the future to argue cases on the basis of equal protection principles or from the perspective of the right to privacy. A theme that surfaced repeatedly was the impact that the AIDS epidemic was having. It was stoking deeply irrational fear and prejudice, encouraging more overt discrimination, and justifying that discrimination because of the threat to public health.

Yet there was also a fighting tone to many of the presentations and discussions. Despite the loss in Hardwick, speakers agreed that it was “a risk we had to take.” The loss in the Supreme Court would encourage activists to work for state repeal and lawyers to explore whether some state constitutions might provide grounds for court challenges. Discussions of family law seemed to produce a great deal of energy. In 1987, no state sanctioned same-sex intimate relationships, and state cases about child custody for lesbian mothers were mixed in their outcome. Anticipating the intensifying focus that the 1990s and beyond would bring to marriage and other forms of family law, Abby Rubenfeld stated unambiguously that “we need the sanction of the state” and Nan Hunter declared “we should have it all.” Hunter explained her support of a fight for access to marriage in terms of “the power of marriage as a symbol.”

Most of all, perhaps, the conference was valuable because of the power of bringing so many legal activists together to discuss what the future might bring. As Keller described it in a letter he wrote when he donated the papers to Gerber/Hart, “it was a hugely exciting event – the air was alive with crisis and possibility.”

In the Archives | The 1987 March on Washington Committee: The Chicago Chapter

BY John D'Emilio ON December 21, 2016

While the archival collections at Gerber/Hart are grounded in the history of Chicago, inevitably some of the papers reach beyond the city to illuminate national events. They reveal connections between the local and the national and the impact of each on the other. The papers of the Chicago chapter of the 1987 March on Washington Committee are a case in point.

While the archival collections at Gerber/Hart are grounded in the history of Chicago, inevitably some of the papers reach beyond the city to illuminate national events. They reveal connections between the local and the national and the impact of each on the other. The papers of the Chicago chapter of the 1987 March on Washington Committee are a case in point.

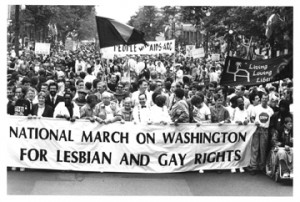

The importance of the 1987 March on Washington cannot be overstated. It put the organized LGBT community on the national stage as never before. There had been a first lesbian and gay national march in 1979, but it drew fewer than 100,000 people to Washington. By the standards of the time, that marked it as decidedly unimpressive. By 1987, just eight years later, much had changed. The AIDS epidemic was raging across America, killing men who had sex with men in staggering numbers. The Reagan administration was disgracefully ignoring it. In 1986, in Bowers v. Hardwick, the Supreme Court added to the fury by upholding the constitutionality of state sodomy laws, with language that was gratuitously contemptuous of same-sex love and relationships. Put all this together, and the result was a march of 500,000 people in October 1987, perhaps the largest protest march to ever assemble in the nation’s capital.

But there was more. There was also mass civil disobedience and arrests in front of the Supreme Court, a mass wedding of same-sex couples to protest the absence of family recognition, and the powerful display, for the first time, of the Names Project Memorial Quilt on the Washington Mall. Key speakers at the rally were the Reverend Jesse Jackson, long-time African-American civil rights leader and a candidate in 1984 for the Democratic presidential nomination; Cesar Chavez, head of the United Farmworkers Union and perhaps the most visible Chicano leader in the U.S.; and Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization for Women, the largest feminist organization in the United States. Their participation was a dramatic sign that the LGBT movement had come of age and was recognized as a component of the broad struggle for social and economic justice in the United States.

Materials in the papers of the Chicago’s MOW Chapter provide a glimpse into just how wide and deep the organizing for the March was. The national steering committee had representatives from 18 states, and there were local committees in 43 states. For instance, three cities in Alabama, six in Georgia, and three in Maine had an organizing structure to get people to Washington. The Chicago chapter papers contain a list of endorsers of the March that filled several pages. It included labor unions, religious groups, and women’s organizations, as well as national, state, and local elected officials. It is worth remembering that every one of those endorsements came because an LGBT activist reached out to key figures in those groups, talked about the March and the issues, and persuaded them to lobby within their organization for an endorsement.

The papers also contain extensive materials about civil disobedience and the kind of training that was provided to individuals. A condition of joining in the civil disobedience outside the Supreme Court was that participants belong to a local affinity group. This meant that, in the summer and early fall of 1987, deep and trusting relationships were forming among groups of activists in cities across the country. As I looked through this material I could not help but wonder how much this contributed to the explosion of local direct action protests by ACT UP and other AIDS-activist groups in the months after the March on Washington, both in Chicago and around the country.

Besides the window that this collection opens into the scope and reach of national preparation, it also naturally gives a close sense of what the organizing looked like and accomplished in Chicago. Julie Valloni and Victor Salvo were the co-chairs of the Committee. In the course of organizing Chicagoans to go to Washington, they and other committee members sought local endorsements, a process that undoubtedly built support for a city non-discrimination ordinance which still hadn’t passed in 1986-87. They also worked closely with media in Chicago; one result was front-page coverage of the March by the Chicago Sun-Times. Perhaps the most visible local achievement was the endorsement letter the Committee received from Mayor Harold Washington. “It is with enthusiasm that I endorse the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights,” he wrote in his letter of September 17. “The breadth of the issues highlighted by the March – against racism and apartheid, as well as for civil rights – is consistent with the historic thrust of struggles for civil rights in this country.” Working hard to get a civil rights ordinance passed in Chicago, Mayor Washington also wrote: “The March will in turn support passage of a comprehensive Human Rights Ordinance here in Chicago.” Such a law was finally enacted a year after the March on Washington.

Besides the window that this collection opens into the scope and reach of national preparation, it also naturally gives a close sense of what the organizing looked like and accomplished in Chicago. Julie Valloni and Victor Salvo were the co-chairs of the Committee. In the course of organizing Chicagoans to go to Washington, they and other committee members sought local endorsements, a process that undoubtedly built support for a city non-discrimination ordinance which still hadn’t passed in 1986-87. They also worked closely with media in Chicago; one result was front-page coverage of the March by the Chicago Sun-Times. Perhaps the most visible local achievement was the endorsement letter the Committee received from Mayor Harold Washington. “It is with enthusiasm that I endorse the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights,” he wrote in his letter of September 17. “The breadth of the issues highlighted by the March – against racism and apartheid, as well as for civil rights – is consistent with the historic thrust of struggles for civil rights in this country.” Working hard to get a civil rights ordinance passed in Chicago, Mayor Washington also wrote: “The March will in turn support passage of a comprehensive Human Rights Ordinance here in Chicago.” Such a law was finally enacted a year after the March on Washington.

The last thing I’ll mention about this collection is a laugh that it elicited. In October 1986, the Vatican issued a major document on homosexuality that provoked a great deal of criticism and outrage, since it supported a theology that defined homosexual behavior as criminal. But one result was that, in Chicago, it led to the formation of a new group called “P.O.P.E.” The letters stood for “Pissed-Off Pansies Energized.” You’ve got to love our sense of humor!

In the Archives | Go Out and Interview Someone! The Robinn Dupree Papers

BY John D'Emilio ON November 30, 2016

Our life stories are the core content of LGBT history. Yes, our organizations and businesses produce records that detail important work. And mainstream institutions and social structures affect us deeply. But the texture and the challenges of what it means to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender at different times and in different places will only fully emerge if we make an effort to collect a broad range of our life stories. Reading – or hearing – the life story of an individual is not only compelling and absorbing in its own right. It can also open doors of understanding and offer revealing insights into what it was like to be . . . well, whatever combination of identities the individual brings to the interview. Each of our life stories will have something to tell us beyond the L,G,B, or T. We are also the products of regional culture, of racial and ethnic identity, of religious upbringing, of our particular family life, of class background, of work environments, and other matters as well.

The truth of this was brought home to me when I stumbled upon the small box of papers at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives labeled “Robinn Dupree.” In November 1996, a professor in folk studies at Western Kentucky University took his class of graduate students to Nashville to see a performance of female impersonators at a bar, The Connection. One of those students, Erin Roth, was so impressed by the event and by the lead performer, Robinn Dupree, that she asked for permission not to do her seminar paper on the assigned project – interviews/studies of “riverboat captains and old-time musicians” – but instead be allowed to interview Dupree and write about the art of female impersonation. The professor said yes, and so Roth conducted two interviews with Dupree, in March and April 1997. Fortunately for everyone else, she donated the tapes, a typed transcript, and her seminar paper to Gerber/Hart, so that Dupree’s account of her life is now available for study and inclusion in our collective history.

To summarize her story briefly: Dupree was born in 1952 in Chicago, her mother of Sicilian background and her father a Puerto Rican of African heritage. When she was in the 8th grade, she told her mother she was gay. As a teenager, she discovered the Baton Show Lounge, run by Jim Flint and already well-known for its performances by female impersonators. Soon she was sneaking out of the house to go there regularly. “It’s like I found what I wanted to do,” she told Roth, and soon Flint was coaching her and she began performing regularly.

Dupree performed at the Baton for almost a decade, and then moved on to another club, La Cage. In 1982, her boyfriend of ten years, who had connections to the Mafia, was killed in a car bombing outside their apartment building. Dupree realized it would be best to leave Chicago quickly, and she resettled in Louisville, Kentucky, where she rapidly made her way into the local female impersonator scene. Over the next decades, she performed for long stretches in Louisville, Nashville, and Indianapolis. According to online sources, her last show before retiring as a performer was just a few months ago, on February 13, 2016.

Reading the transcript of the interviews as well as Roth’s paper, I was struck by certain themes, some of which likely have broad applicability and some of which might be particular to Dupree. One involves economics. For those like Dupree who take the work of impersonation seriously as an art form and devote themselves to it, the economic realities can be harsh. On one hand, costs are high: the dresses, the jewelry, and everything else associated with the glamor of their performance are expensive, and new apparel has to be bought regularly for new shows. On the other hand, wages are low. Performers depend on tips, but these are unpredictable and often will not support them sufficiently. Thus, most impersonators need to have a day job, but that brings them up against the gender boundaries of the culture.

Another theme is family. As Dupree became a well-known, successful, and seasoned performer, younger impersonators-to-be came to her for advice, tutoring, and support, just as she had received from Jim Flint when she was starting and barely out of her teens. To many, she was their “mother,” and to Dupree, they were her “daughters.” The terms conjure up images of a warm and intimate family of choice, which it is. But behind the pull to use those terms is a harsh reality. After Dupree started performing, her biological mother broke off contact with her, and they remained separated for ten years. “Most people who do drag or want to become women, their family totally disowns them,” Dupree told Roth in their interview. Although Dupree acknowledged that much had changed in the 25-plus years since she had started performing, the loss of connection to families of origin remains true for many. Thus the relationships that were established had significant emotional and practical meaning. Dupree’s daughters often lived with her for long stretches as they worked to establish a life for themselves. Yes, it was a chosen family, but it was also a deeply needed family.

A third issue emerged in reading the interview with Dupree: the complexities and shadings of identity. At the time of the interview, in 1997, transgender had just recently established itself as a term of preference in the LGBT movement and in activist circles. Dupree described herself as “a pre-operative transsexual . . . I live every day of my life as a woman.” She had had surgeries done on her face to accentuate a kind of feminine beauty. She had also done hormone treatments in order to increase her believability as a performer in the world of female impersonation. “That’s why I actually ended up taking hormones and becoming a pre-op,” she told Roth. “Not to become a woman, but to look as much like a woman on stage as possible.” And within this world of stage performance, at least in the decades in which Dupree was an important presence, a range of self-understandings existed. “I have some daughters who want to be just entertainers. Then I have other daughters who want to go all the way through and become a woman.”

The Dupree oral history at Gerber/Hart is a treasure. We need more of them. Go out and interview someone – now!