Posts by Eric Gonzaba

Eric Gonzaba is currently a PhD candidate in American history at George Mason University. He is currently working on his dissertation, “Because the Night: Nightlife and Remaking the Gay Male World, 1970-2000,” which examines resistance to racial discrimination at gay nightlife in Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and Philadelphia.

Look to the Past: Our Military Grows With Inclusion

BY Eric Gonzaba ON August 28, 2017

In this post, historian Beth Wolny explores US military integration in the wake of trans service ban.

In this post, historian Beth Wolny explores US military integration in the wake of trans service ban.

She is introduced by Eric Gonzaba.

A few weeks ago, President Trump announced his intention to ban transgender people from United States military service. This move reverses the Obama Defense Department’s policy push to allow transgender people to serve openly. Since the sudden announcement, I’ve been happy to read some incredible response pieces on trans military service, including Landon Marchant for the Point Foundation and two great stories from OutHistory.

To make even more sense of this nonsensical action, I reached out to a historian friend of mine who graciously offered some different historical perspective. Lt Col.

Beth Wolny not only has an insanely impressive title I’ll never hold, but she is also a doctoral candidate in the history department at George Mason University specializing in military women’s history. She recently published “Female Marines Guard the Embassies: An Experiment in Social Progress and Cultural Change” in the International Journal of Naval History.

Beth is not an LGBT historian (sigh…), but her research on military integration and her own military service offers a great perspective on military and civilian politics regarding transgender ban.

Our Military Grows With Inclusion

By Beth Wolny

The military rarely, if ever, accepts change easily. The service protested against racial integration, gender integration and homosexual individuals serving openly. In each instance, senior leaders argued changes were unnecessary; that they would threaten cohesion and morale (and thus, it was assumed, combat effectiveness). In sum, it wasn’t worth it. But what is “it”, exactly? When President Trump tweeted that he has consulted with his “admirals and generals” and decided that transgender individuals cannot serve “in any capacity”, he acceded to the military’s desires but not necessarily to the nation’s best interests or even its military’s combat effectiveness.

During and after World War II, the services fought having African Americans in the ranks. U.S. Marine Corps Commandant Thomas Holcomb stated that given the choice between 5,000 white Marines or 250,000 black Marines, “I would rather have the whites.”[1] Despite the need for additional manpower, General Holcomb would have preferred to risk combat lethality than to accept African Americans. The U.S. Navy made African Americans cooks. The U.S. Army created separate ranks, away from the fighting, for African Americans. Yet how combat effective would the U.S. military have been in that war without its African Americans?

Women have faced similar challenges. Marginalized as mostly secretaries until the mid-1970s, women fought for equal pay, recognition and treatment at each step. In 1979, Marine Corps Commandant Robert Barrow stated,

The simple facts are we don’t need them. We can get all the males to do whatever needs to be done . . . so why experiment . . . because someone can make a boast or a claim that you have broadened the opportunity for women.[2]

General Barrow is speaking directly to the military’s constant concern – that politicians may prioritize inclusion to the detriment of combat effectiveness. When a traditional culture – such as the military – experiences any kind of cultural change, there will be pain. There may be violence. It may take a generation for cultural changes to solidify. Then there is growth and actually – a more combat effective military. Women’s roles in Iraq and Afghanistan, especially as Lionesses and as Female Engagement Team (FET) members, demonstrate how much our military benefits from the inclusion of all. Or do we currently not have the most powerful and lethal military in the world?

Almost a generation ago, Congress passed Don’t Ask Don’t Tell (DADT), which permitted homosexual members to serve, but in secret. The military moved forward under the auspices that if no one knew the sexual orientation of the other person in the fighting hole, then it did not matter. Did it really matter at all? Or did what matter was whether or not a person could do the job?

The repeal of DADT proved what the military had already learned through racial and gender integration. The most important aspect of any individual serving in any capacity in the armed forces of the United States is whether or not they can do the job – and that means whether or not service members trust that each member of the team is able to do the job. Cohesion and morale grow when individuals trust each other, through tests of capability and endurance. This is task cohesion, and this is what really matters to combat effectiveness. Military leaders more often worry about social cohesion – whether or not members of a group get along or like each other – and assume that social cohesion is necessary for task cohesion.

Marine Corps Commandant Amos went on record about the threats to cohesion and morale, DADT and combat effectiveness. In December 2010 he stated that on the battlefield, “you don’t want anything distracting. . . . Mistakes and inattention or distractions cost Marines’ lives.”[3] Today, service members of any sexual orientation are serving openly and with acceptance. The concerns over “distractions” and cohesion proved unfounded.

All of these concerns are the real reasons behind the reluctance to admit openly serving transgender service members – the desire for the known versus the new; the concern over politicians prioritizing inclusion over combat effectiveness and threats to cohesion and morale (and thus combat effectiveness). While these concerns will certainly require strong departmental policies, solid guidance and strong leadership to implement those policies, they are not reasons to restrict transgender members. Our military grows with inclusion. The integration of transgender individuals will proceed along similar lines to every other instance of integration. The process will be difficult. There may be protest. There may be violence. It may require a generation. Let’s hope it doesn’t, because in the end, it will be worth “it” because it will result in a stronger, more combat effective military.

[1] Nalty, Bernard G., “The Right to Fight: African-American Marines in World War II”, Marines in WWII Commemorative Series, Marine Corps History and Museums Division, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extcontent/usmc/pcn-190-003132-00/sec1.htm, accessed 7 August 2017.

[2] Robert General Barrow, Session XV, Transcript, December 20, 1991, 8, Archives and Special Collections Branch, Library of the Marine Corps.

[3] Whitlock, Craig. “Marine general suggests repeal of ‘don’t ask’ could result in casualties”, The Washington Post, 15 December 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/12/14/AR2010121404985.html, accessed 8 August 2017.

Emerging LGBTQ Scholars Reflect on Dawn of Trump Presidency

BY Eric Gonzaba ON January 2, 2017

I like to think of OutHistory as a sort of historical queer think tank, allowing scholars and the wider public alike to engage with LGBTQ studies and to ponder difficult questions about sexuality and gender. The OutHistory team graciously lets me muse about various topics from time to time, and America’s fractured political atmosphere seemed an obvious angle on which to write. However, with a Trump presidency just on the horizon, collaboration with various colleagues seemed more fitting a means of contemplation.

Below, I’ve invited a group of emerging LGBTQ scholars to reflect on the era of Trump, curious of what they think led to this man’s ascendency to the highest political office in the land, how they believe his administration will affect current LGBTQ movements, and in what way their own work in LGBTQ studies reflects the current political atmosphere. These individuals represent the future of LGBTQ scholarship. If their words indicate anything, it’s that the vigorous study of the queer past and present appears in good hands.

Best,

Eric Nolan Gonzaba

——————————————————————

Harrison Apple, Our Situation is White Supremacy and Mass Incarceration

Rachel Gelfand, Surveillance Constancy: Trump on the Threshold

Eric Nolan Gonzaba, The Queer Arc of Justice

Daniel Manuel, Complexity Can Give Us Hope

Sarah Montoya, We Stand On the Backs of Many

Chris Parkes, Reflecting From Across the Pond

Kristyn Scorsone, Oral Histories Speak Truth to Power

Terrance Wooten, Against the Romance of Futurity

.jpg) Our Situation is White Supremacy and Mass Incarceration

Our Situation is White Supremacy and Mass Incarceration

Harrison Apple

PhD Student, Gender & Women’s Studies, University of Arizona

Co-Director, Pittsburgh Queer History Project

In the summer of 2016, I was interviewing a woman as a part of my research on working class LGBT history in Pittsburgh, PA. Speaking about her feelings of contradiction she said, “for being gay, I have liberal policies on some things, but very conservative on others…” She then asked me, “Who do you like for President?” I had never been asked that question in an interview before, and I quickly began to ramble before settling on, “I just don’t know.” Mirroring her, I asked who she liked and she said, “I’m leaning towards Trump.”

I reflect on that conversation often, and the way she phrased it. “Who do you like?” sounded as much like a bet as a preference. Perhaps interpreting it as a bet was a form of disavowal. Rather than believe someone when they tell you that their imagined future is anchored in your own oppression, I pretended she was making due with her options, in the same ways he described her distaste for political correctness and our waning ability to take a joke.

Moments like these – of which there are plenty, believe me – demonstrate what I believe Teresa de Lauretis meant when she said, “the time for theory is always now.” Regardless of who is elected, in the next four years we are all going to be asked to make decisions that we will want to believe are unmotivated, objective, or neutral when they are not. We will be asked to preserve our own sense of security-futurity through the punishment-death of others.

This is by no means a new phenomenon. For many, the reality of a Trump presidency may mean little substantial shift in their everyday lives. The white supremacy that was eluded to by the woman I spoke with, saying that political correctness has hindered out ability to effectively enact racially profiling and support homeland security, is only one manifestation of anti-blackness that subtends LGBT U.S. history as a frequently deracialized field of study.

Rejecting the reality that a rights-based political platform is made possible with the same apparatus that has subtended white supremacy and cishetero-patriarchy (such as the prison industrial complex, overreaching surveillance, and dubious hate-crime legislation) is another form of disavowal. I’m reminded of Jonathan Ned Katz’s introduction to Gay American History in which he says, “all homosexuality is situational.” A political climate of white supremacy and mass incarceration is our situation. It is our responsibility to think through it.

——————————————————————

Surveillance Constancy: Trump on the Threshold

Rachel Gelfand

PhD Student, American Studies, University of North Carolina

Outhistory is a space, digitally housed, for historicizing queer movements. It holds what Ann Cvetkovich termed “archives of feeling,” an attention to the loves, losses, and liminalities of queer historical subjects. My research for the last few years has attended to questions of intergenerational history-making, the transmission of gay and lesbian activist strategies, and the passing along of experiences of surveillance. I am interested in how archives and oral history offer forms of time travel that transgress while simultaneously being institutionally bound, preserved by universities, libraries, government bureaus.

Living in North Carolina, I have focused on the Atlanta Lesbian/Feminist Alliance and traced how founding members “came out” of left movements. Many Atlanta feminists were on Cuba’s Second Venceremos Brigade, a part of Civil Rights activism, and key organizers working against the Vietnam War. For these actions, surveillance followed. While FBI agents struggled to find information about lesbian feminists, their presence was soon felt. In Atlanta, the FBI arrested an ALFA member in her lesbian collective house for antiwar activities. In Lexington Kentucky, a grand jury probed local lesbian connections to Susan Saxe, an underground lesbian activist.

With Donald Trump’s impending inauguration, my thoughts have been on his connections to this lineage of surveillance. I have been reading Simone Browne’s Dark Matters, in which she historicizes surveillance and its counterpart sousveillance, the people’s capacity to record state mechanisms. Surveillance systems grew out of histories of colonization and enslavement, a centuries-long process of biometrics. In my own research, I see cyclical fears of FBI presences. COINTELPRO and the anxiety it mustered echoed the McCarthy era of ALFA activists’ childhoods. Grand juries mirrored the House Un-American Activities Committee. Trump’s ideologies resound those of his mentor Roy Cohn, Joseph McCarthy’s star litigator (famously depicted in Angels in America). J. Edgar Hoover’s wiretap methods have played out on a digital scale in my lifetime and it seems the NSA’s role will only intensify. Reflecting on these connections, I think of my grandparents and great-grandparents living in Trump’s Brooklyn tenements. I think of my lesbian mother’s red-diaper-baby childhood and the fear she carries today.

Last Friday, I went to a protest here in Raleigh. Republican state legislators were in the process of passing bills to strip the incumbent Democrat governor of that post’s customary powers. Protests were loud and coalition-based, but Republicans did not bat an eye. With both press and police filming protestors, state legislators voted unviewed.

My time in North Carolina has made me acutely aware of legislative violence. Trump is one thing—something quite scary. His presidency emboldens patriarchy. The bullying culture he incites inherently hurts minoritarian communities, hurts queer people. But the racism of federal and state legislatures works on the level of the everyday. While Trump stokes white fears of a demographic shift toward black and brown political power, Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell stall on passing an updated Voting Rights Act. The lack of preclearance, or federal oversight of voting law, is felt in quotidian life. The Supreme Court’s 2013 decision to gut the Voting Rights Act has led to violence that cuts across identity categories. In North Carolina, legislative gerrymandering has precipitated HB2, no Medicaid expansion, ransacked public education, voter suppression, and measures against police transparency. At Friday’s protest it was clear: the same politicians who are transphobic, are racist, sexist, anti-worker, xenophobic, islamophobic, and are swiftly moving on legislation in line with those ideologies. As a queer Jewish historian, I hope the Trump years increase solidarity and the fusion politics North Carolinians utilize. I hope, for example, Jewish communities will ally with Muslim communities.

Surveillance for my generation has been a constant. But for me it has been helpful to understand the racist historical underpinnings that produced the data-driven system we live within. My study of lesbian activism has been grounded in ALFA’s grassroots archives and FBI archival materials. I encourage historians thinking about this historical moment to look to both those archives for insight into creative resistance (radical softball teams, newsletters, bar life) and surveillance’s stumbling blocks. For historians of queer life, this work must continue to be framed by intergenerational dialogue. Outhistory can be a great resource toward these ends!

——————————————————————

The Queer Arc of Justice

Eric Nolan Gonzaba

PhD Candidate, History, George Mason University

Director, Wearing Gay History

Echoing the words of 19th century abolitionist clergyman, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. proclaimed many times throughout his life “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Assuming King is right (and that’s a big assumption) after the recent election, it’s really hard to see that bend, especially if you’re a person with a disability, someone of Latino heritage, a Muslim seeking asylum in the “land of the free,” or anyone who understands that grabbing anyone by their private parts without consent constitutes sexual assault.

And yet, Donald Trump won a majority of votes in the Electoral College, and will become the 45th US President. President Obama’s departure from the White House seems so devastating to so many LGBTQ people because the Obama years felt like an era of change. Certainly there were big victories—marriage equality, the end of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, the election of the first openly lesbian woman to the US Senate and the first openly bisexual person to become a governor. President Obama’s Attorney General Loretta Lynch even launched a suit against North Carolina and it’s anti-trans bathroom law. On behalf of the administration she served in, Lynch told trans communities that “we see you; we stand with you; and we will do everything we can to protect you going forward.”

There were also setbacks—the continuing attacks on trans people, especially trans women of color, persistent bullying in schools, the passage of so called “religious freedom bills” in GOP controlled statehouses, and the fact that LGBTQ people made up the vast majority of victims at the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil since 9/11.

As historians, Trump’s victory is a call for us rethink how we teach history. The cliché answer students give me when I ask “why do we study history,” is some variation of the famous Santayana quote “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” I mean . . . I guess? Though, I know lots of historians and we aren’t an army of modern Nostradamuses over here. Historians can certainly inform the present and give us tools to shape our futures, but I often respond to this answer by asking my students why they assume we’re living in some utopia compared to the past? Maybe those who cannot remember the past are condemned not to repeat it. Imagine for a moment future Attorney General Jefferson Beauregard Sessions ever telling transgender Americans that they have a friend in the Trump administration. While we all may be guilty—at times—of interpreting the past through rose colored glasses, it is clear that our future is no safe haven.

The Obama years were—by no means—Camelot, but the social progress during those eight years for some queer people was laid brick by brick by those who fought decades and centuries earlier. Our queer past isn’t something we study to pat ourselves on the back; rather, these requisite recounts of past tragedies and achievements give us necessary perspective to celebrate change and acceptance. More importantly, this history should embolden us all to fight injustices that some continue to overlook—and many continue to endure. The comfort of a supportive president is gone, and along with him should go our complacency to challenge and fight inequalities.

King may have been right; the arc may bend toward justice, but let’s not wait around to find out. We ought to bend it ourselves.

——————————————————————

Complexity Can Give Us Hope

Daniel Manuel

PhD Student, History, Rutgers University

I am a historian of the AIDS crisis in Louisiana in the 1980s and 1990s. I spent the first twenty-four years of my life in Louisiana, and my research is as much an effort to understand the world in which I came of age as it is an effort to historicize why Louisiana is at the forefront of the contemporary HIV epidemic.

Yet, my work also recognizes possibilities for resistance, even in hostile times and places. In recent days I have conceived of my work, and the work of historians, as arguing for the complexity of the past. Under an administration whose campaign suppressed narratives it found troublesome and rejected complexity in favor of simplistic mantras, historians are truly obligated to uphold complicated truths. In this disempowering post-election moment, a complicated past is a powerful past. I would like to explain by offering a few takeaways from the history of AIDS activism:

The Right is not monolithic. Historians, including Jennifer Brier in Infectious Ideas, have highlighted Republicans’ fault lines during the Reagan administration, as multiple issues divided the Right in the 1980s. Gary Bauer and other members of Reagan’s cabinet sharply conflicted with Reagan’s own Surgeon General, C. Everett Coop, over the administration’s approach to preventing HIV transmission. Similarly, we witnessed Trump’s difficult relations with the Republican establishment during the primaries, and, while many establishment figures have attempted to atone for earlier disagreements, the Right remains visibly fragmented. We should recognize that Trump’s administration comprises cabinet members and advisers with competing interests and outlooks. Despite the wishes and pronouncements of Trump and others, the Right is not unified, and its internal disagreements are potential sites of challenge and contest.

The Left lives on. Particularly when riven by internal conflict, the Right cannot quash all opposition. Populations and people marginalized by Trump’s victory are not powerless. Even in moments when conservative social and political messages predominate, they do not stymie the vital and ongoing work of the Left. Our organizing efforts endure, perhaps with renewed vigor and inspiration in the face of a hostile political administration and social climate. What we have to recognize is that the Left is alive in ways that are often ignored. In the 1980s everyday actions, like grocery shopping for a person with AIDS or writing a letter to a newspaper editor about living with HIV, were profoundly powerful. We can remember that in uncertain times, as the AIDS epidemic began to rage in the early 1980s, marginalized populations banded together to care for one another. These simple acts disrupted and displaced, even if temporarily, public rhetoric and attitudes that were heterosexist, racist, misogynistic, and classist. These simple acts asserted the value of lives deemed worthless by mainstream conservative attitudes. Many disregarded the social stigma attached to AIDS to care for friends, family members, lovers, and strangers. These practices were never perfect, and we should keep in mind the need for intersectional organizing, as we simultaneously reject limited conceptions of community. Nonetheless, the Left is alive and powerful.

Accordingly, we should recognize local and everyday politics as sites to challenge oppression. National elections and legislation are not the only measures of power. As HB2, the transphobic bathroom bill, in North Carolina and the recent rash of legislation restricting abortion access in Ohio and Texas have shown, we will be fighting for bodily autonomy and personal dignity at the state and local levels, too. Moreover, we have to remember that political power also lies beyond legislation. Local organizations provided the first care for people with AIDS, and I think often of what it meant to care for a person with AIDS before the advent of life-sustaining drugs. By refusing to let lives slip away and refusing to let people die in degrading circumstances, AIDS activists sent a political, life-affirming message. Caring for one another is a potent and meaningful political and human victory.

All this to say, historians are obligated to challenge narratives that claim the Right is all-powerful, that the Left is utterly lost, or that national electoral and legislative victories are all that matter. The present, like the past, is more complicated. That complexity can give us hope to carry on.

——————————————————————

We Stand On the Backs of Many

Sarah Montoya

PhD Student, Gender Studies, University of California, Los Angeles

In the days after the election, I found myself profoundly numb. The stillness was only periodically punctured by waves of fear and anger. As a victim and survivor of domestic violence and sexual assault, I wept. As a queer woman of color, I wept. For two weeks, I recoiled into myself and did not write. But I knew better than to ask the question, how could this happen?

The ideology and political, imperialist practices of this country are deeply invested in a white supremacist capitalist heteropatriarchy. The creation of this country was and remains contingent upon the dispossession of Native peoples and the systematic denial of their sovereignty. The American economy was built upon the backs of Black slave labor. It remains contingent upon the exploitation of people of color both here and abroad. This was never a place that offered recognition or protection to Black folks, Native folks, or queer folks of color. The promises of citizenship and legal recognition or protection have largely been illusory. Today, we see this legacy of violence at Standing Rock, in the state-sanctioned murders of men and women of color in our streets, in the brutality visited upon transwomen of color, and the rampant xenophobia aimed at Muslim communities and the undocumented.

For many of these communities, life will continue to be as precarious as it has always been. Perhaps we can begin the necessary work by holding ourselves accountable. I am a Ph.D. student at a Tier-One University on what was once Tongva territory. I value my work as an educator, but I am not naïve to its context. The university is, first and foremost, a business. The work I do is only valuable if it is accompanied by daily practice and I am willing to put my energy into the community outside the university grounds. We must continually ask ourselves, how can I be of service to the community? How is the work that I am doing helping to redistribute resources to those most vulnerable?

We cannot build radical communities or movements if we do not grapple with these realities. Many of us were not afforded the luxury and privilege of “shock” at this election’s outcome. We cannot afford to confuse progress towards social justice with neoliberal progressive politics. Here, we see the failure of single-issue politics and the need for intersectional analysis and political practice. Our political agendas should advocate for those continually and repeatedly rendered most vulnerable. To celebrate our existence is not enough, and our mobilization in the wake of a Trump regime means that coalition building is crucial.

In “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” Audre Lorde writes, “For to survive in the mouth of this dragon we call america, we have had to learn this first and most vital lesson – that we were never meant to survive. Not as human beings. And neither were most of you here today, Black or not. And that visibility which makes us most vulnerable is that which also is the source of our greatest strength.” Lorde delivered this paper in 1977, and, nearly forty years later, the sentiment rings true. There is a long and storied history of survival and resilience around us – in the faces and stories of our elders and in the literature of women and queers of color. This is not the first time that we are struggling against domination and injustice. We are not doing this alone; we stand on the backs of so many.

——————————————————————

Reflecting From Across the Pond

Chris Parkes

Graduate Teaching Assistant, International History, London School of Economics and Political Science

More than once in the past month I have encountered historians here in the UK contemplate refusing to return to the United States because of the election of Donald Trump. There is something about the prospect of his presidency that fills some Americanists in this country with a palpable sense of revulsion. Much of it is distaste at the xenophobia, racism, sexism, homophobia, and a litany of other obloquies that can be rightly leveled at the candidate and his campaign. But there is something deeper, too. Perhaps it is the inevitability of having to see Mr. Trump’s incandescent mug displayed in the entryways to the National Archives and the Presidential Libraries in which we conduct much of our research. More likely it is a sense of anguish, despair, or even betrayal that the United States – a beacon of hope amid the gloominess of Britain’s Brexit winter – would succumb to the same populist backlash that has roiled this country. Best to turn our back, impose a personal embargo on the Yanks, and hope things turn around in four years time.

Those of us outside the US have the luxury of being able contemplate such remedies. But how much comfort does distance really provide given the enormity of recent events? For LGBT historians in particular the populist revolt of recent years portends a deeper crisis. The rise of the far right in France, the Netherlands, and other European countries, the clampdown on academic and press freedom in Turkey, the spike in hate crimes in the UK following the victory of the Leave campaign in the EU referendum, and, of course, Mr. Trump’s election represent not only a rejection of ‘elites’ but also a repudiation of the pluralist ethos that has underwritten the study of sexuality as a historical subject. For a (sub)discipline built on the recognition of the lives of the powerless, the nonconforming, and the despised, validation of casual bigotry and alt-right authoritarianism by the imprimatur of electoral success poses an existential threat.

If this sounds alarmist, it should. LGBT historians have a particular incentive to speak out in times of rising intolerance to dissent. Our subjects and their stories are salient because, more often than not, they concern those who occupied the margins of society. They were the first targets of oppression by the state, the mob, and civil society when demagogues fanned populist anger or induced people to look for scapegoats. Sexologists in Weimar Germany, gay and lesbian civil servants in the Federal Government during the Lavender Scare, and radical AIDS activists during the 1980s, to name but three examples, all endured official opprobrium in a political climate that deemed sexual diversity to be dangerous. Studying their successes and failures reminds us of how tenuous gains in civil rights can be and how intolerance of one minority group is rarely an isolated lapse in a society’s treatment of its most vulnerable citizens.

Bearing this in mind, LGBT historians in the coming years can reassure themselves that they have more resources, colleagues, and platforms to draw on than preceding generations did. The interconnectedness of contemporary scholarship – spanning continents and crossing disciplines – provides an armature to withstand the coming trials, provided we keep speaking out and do not stay home hoping it will all pass.

——————————————————————

Oral Histories Speak Truth to Power

Kristyn Scorsone

MA Student, History, Rutgers University – Newark

Team Member, Queer Newark Oral History Project

In the short time we have before the President-elect takes office, scientists are pushing to archive as much U.S. government data on climate change as possible. According to a recent article from the Washington Post, the scientific community is highly concerned about the new administration’s bent towards scientific suppression. Although the inauguration is still a few weeks away, there has already been an insidious request by Trump’s transition team for lists of Energy Department employees and contractors who have taken part in climate change talks. To date, the Energy Department is resisting and in Toronto, climate change data from the Environmental Protection Agency will be mass copied as part of a “guerrilla archiving” hackathon event.

As these storm clouds continue to gather over our political landscape and the word of the year is “post-truth,” the work of the Queer Newark Oral History Project feels more crucial than ever. Writer and activist Darnell Moore, who was also the first chair of the City of Newark’s Advisory Commission on LGBTQ Concerns, Rutgers-Newark history professor Beryl Satter, and Rutgers-Newark Department Administrator for History and African American and African Studies Christina Strasburger started the project in 2011 as a community-based and community-driven endeavor. Queer Newark’s focus is to document Newark’s urban communities of color in an effort to expand the dominant historical narrative, which largely ignores the contributions of queer people of color. In Trump’s Amerikkka, lies made up of 140 characters are eaten up by far too many people convinced a billionaire has their best interest at heart, while in depth political analysis and fact-finding by reputable journalists gets dismissed as “butthurt” rants. It is hard to say where the obfuscation of truth will extend its reach next. Therefore Queer Newark, and public history projects like it, are more than a repository of human experience, they become an important part of the defense against authoritarian influence.

While Tony Perkins, Trump ally and head of hate group, Family Research Council, calls for a “purge” of pro-LGBTQ employees from the State Department, Queer Newark provides a counter-narrative to the spread of hate speech and misinformation dangerously hostile to queer individuals and families. On our website, black lesbian narrators like Renata Hill and Venice Brown—two of four friends who were characterized by the news as a “Gang of Killer Lesbians” and sent to prison for defending themselves against a man who violently attacked them because of their sexuality—expose the intersections of racism and homophobia in our court system and media. You can also listen to Alicia Heath-Toby describe what it was like for her and her partner to be the only African American lesbian couple in the 2006 legal battle for marriage equality in New Jersey. Without the preservation of stories like these, the new administration’s vision for our nation gains another foothold.

Michel-Rolph Trouillot in his book, Silencing the Past: Power and Production in History, writes, “History is the fruit of power, but power itself is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous. The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.” (xix) We must question what truths are lost from our historical records in order to dismantle dangerous ideologies of hegemonic forces. If you allow silences in the archive to persist, you allow power to exist unquestioned. The oral histories of Queer Newark speak truth to power. They disrupt the dominant paradigm and disseminate knowledge as a powerful act of resistance.

——————————————————————

Against the Romance of Futurity

Terrance Wooten

PhD Candidate, American Studies, University of Maryland

A little over a month ago I sat with a group of [predominantly liberal, white] coworkers processing various reactions to the outcome of the recent election. During our conversation, they almost uniformly expressed their genuine disappointment in the election results as well as their overall surprise at the increasing intensity with which acts of violence are happening against black and brown people—often queer and women of color—“in 2016.” Their surprise combined with the assumption that these issues should not be prevalent at this particular moment in our history suggests a progressive teleology wherein we should have arrived at a type of multicultural liberalism by now. We should be beyond sexism. And homophobia. And racism. The conversation sounded just like the ones I had with my [predominantly liberal, white] colleagues almost a decade ago during my undergraduate career while recounting childhood experiences growing up in a small rural town in central West Virginia.

My family moved from Sandusky, Ohio to West Virginia the summer before I started the seventh grade. At the time, the only cultural context through which I understood WV was the 1999 horror film The Blair Witch Project, which had just debuted. Needless to say, I was adamantly resistant to transplanting from a place where I had thriving friendships, familial relationships, and “a life” to one where an unidentifiable witch might lurk through the forest to claim my soul. On the first day of school, I found out how wrong I was; besides the fact that I had since dispelled all the myths presented to me in the film, I was confronted with the real threat lurking in the background.

It wasn’t witchcraft; it was racism. Interpersonal. Structural. Systemic. Racism. The stories are endless. Ask me.

That is to say, when I was just twelve-years-old I was forced to think deeply about how race, geography, and sexuality intersected. It was then that I started to realize the tapestry of American empire was sewn together through, against, and on the backs of black and brown folks, that there was no progress narrative to which I could cling, despite my colleagues’ desires, as the only progress I could ever measure was in my own change in height. And yet, every time I retell stories of my childhood, there is inevitably one—or four—person(s) who seems surprised, who is genuinely taken aback by how such racism could exist in 2000 (or 2005 or 2011 or 2016). What this tells me is people are profoundly committed to seeing this moment right now as one that is better than the moment preceding, as understanding the present as much better than the past and the future as always having the capacity to be even better than the now. And yet, there has been a cultural shift (at least amongst many liberals, perhaps exacerbated by Trump’s own campaign refrain to make American great “again,” which is to say to return to the past) since the election wherein the representations of the future have been fraught with a type of nihilistic, post-apocalyptic skepticism that suggests there is nothing forward to which we can look (presuming there ever was). While I want to otherwise resist this impulse, I think this is a productive place to sit for a while—a place of discomfort, a place that queer men and women of color often sit. Not to empathize. Not to know or consume the Other’s pain and trauma and trepidation. To strategize. To rethink time and the value of futurity. To reassess our relationship to the state and to think more critically and creatively about how to engage the state and state agents such that we account for the many people who cannot altogether afford to disavow it—people receiving housing subsidies, affordable healthcare, public assistance, and other forms of social welfare—while simultaneously not reinvesting in it as a site or recovery and retribution. It is a time to not only listen to but also center the voices and experiences of queer people of color. We have to work across and through difference, creating safety networks for when the state works—and it assuredly will—against us.

The day after the election, I did not mourn or cry or panic. Instead, I curled up and reread Wahneema Lubiano’s edited collection The House That Race Built. Not because I am better than or built differently from others but because being a black queer man in America has taught me that Trump is simply an embodiment of all of the intersecting modalities of oppression I—and many others before and with me—have encountered and been fighting against. I hope this moment encourages others to join. Right now. For now. Against the future.

Don’t Get Cozy, Queer Millennials

BY Eric Gonzaba ON November 20, 2015

I’m one of those few people who still reads Time magazine. I know . . . I’m ancient. What’s worse? I still read the paper version of the weekly newsmagazine, and I receive it from a member of the United States Postal Service. Look, I’m working on joining the rest of my digitally savvy generation. I’m proud to announce, for instance, that I recently became a member of the cool kids club and used my iPhone as a boarding pass for a cross-country flight. When my face lit up after the scanner successfully read the phone code, the TSA agent just glared at me all confused. Baby steps. . .

I’m one of those few people who still reads Time magazine. I know . . . I’m ancient. What’s worse? I still read the paper version of the weekly newsmagazine, and I receive it from a member of the United States Postal Service. Look, I’m working on joining the rest of my digitally savvy generation. I’m proud to announce, for instance, that I recently became a member of the cool kids club and used my iPhone as a boarding pass for a cross-country flight. When my face lit up after the scanner successfully read the phone code, the TSA agent just glared at me all confused. Baby steps. . .

As you probably know, cover stories for the American Time usually prove to be nothing more than attention grabbing nonsense. I had little hope for a recent cover story entitled “Help! My Parents Are Millennials,” accompanied by an image of a baby riding in a fancy stroller and accosted by numerous smartphones pointed at his adorable face. I reckoned I was in for another essay of millennial bashing, a now popular activity among hip baby boomer intellectuals. I get the thrust of the concern for my generation; we’re sometimes entitled, self centered, lazy activists, ready to add a filter to our Facebook profile pictures to support marriage equality or show solidarity with the victims of the Paris atrocities, but not that into getting off our couches to do much more than that. It’s certainly easy to broad stroke an entire generation but I’m starting to find it a little lackluster. Why does everything have to result in some kind of generational fight?

Much to my surprise, Katy Steinmetz’s article proved more informative than condescending. Yes, she laid out the quirkiness of the smartphone society, our odd name selections for children, for example, and our exploding “vast archives of selfies.” Still, perhaps it’s the cultural historian in me, but I appreciated the fact that she let millennial parents actually speak for themselves, and the results proved illuminating. Some 50% of millennial parents consciously purchased gender-neutral toys for their children, compared to only 34% of Generation X or baby boomer parents. Millennials, not that surprisingly, overwhelming support same-sex marriage. They tend to care more about issues of sex, sexuality, and gender, and largely want to promote a more equal society for themselves and their kids. Sure, some of the carnivores among us might be alarmed that the occasional millennial parent trains his or her kid to be (gasp!) a vegan from an early age, but no one said the current generation has to be anything like the last one. Let’s remember that, as historians like Elaine Tyler May have argued, even the baby boomer generation fundamentally upended their approaches to issues of sex and sexuality and challenged notions of “normality.”

We ought to be critical of millennial culture but not because of the typical skepticism aimed at the selfie generation. For our queer cultures and communities, the millennial challenge is to not get cozy in the world that’s forming around us. We should combat the comfort that comes with living in a seemingly more inclusive society, because that inclusivity is a mirage to many in our diverse queer communities. That comfort can breed indifference, and with that we forget the immense struggles that queer people continue to face. Look no further than places like Houston, where a group of misinformed Americans convinced an electorate that trans people are mentally disturbed perverts lurking in public bathrooms ready to prey on children. Sure, there was some outrage, but too many of us let the day pass without anymore than a sigh. Imagine the prolonged outcry if, this past June, Justice Kennedy had written that marriage was not a fundamental right.

And then, there is racism. It’s our duty to stop treating non-white gay men in our communities as some sort of tangential concern. People of color and transgender communities are not allies in our collective struggle for acceptance. They are, in fact, the struggle. They face widespread stigmatization, violence, and homelessness, and yet we continue to convince ourselves that we have championed a more tolerant America.

As millennials, we ought to note the lessons of generations before us not to settle within the comfort of apathy and instead make our legacy one of an unrelenting push for an egalitarian world. We’ve already begun building a culture where children aren’t confined to pre-determined dreams based on the baby blue and girly pink toy lines, and it’s heartening that those children will be more able to accept cultural differences because of how the law treats same-sex couples and military service people. However, if that’s our millennial legacy, I’m unimpressed. You’re reading this rambling post on a device that has more technological power and with that more opportunities for learning and engagement than anything known in human history. Yet, we’re living in a world where members of our queer communities face bigotry on a deadly scale.

Let’s end the sighing. Time to get uncomfortable.

Pride (TM)

BY Eric Gonzaba ON June 15, 2015

I couldn’t let June pass without some kind of comment about perhaps the most recognizable LGBT event on the annual calendar, but Pride is a tricky subject to handle. On the one hand, it’s all too easy to make cliché observations about how emancipating it is that our communities can come together nearly a half century after Stonewall and celebrate the enormous progress queer people have made in their search for acceptance and liberation.

I couldn’t let June pass without some kind of comment about perhaps the most recognizable LGBT event on the annual calendar, but Pride is a tricky subject to handle. On the one hand, it’s all too easy to make cliché observations about how emancipating it is that our communities can come together nearly a half century after Stonewall and celebrate the enormous progress queer people have made in their search for acceptance and liberation.

On the other hand, Pride has definitely strayed from its roots. Not that corporate backing is necessarily a bad thing, but the gargantuan presence of corporate sponsorships at many of these parades (Chiptole’s float, for instance, showed pictures of rainbow burritos with clever taglines like “¿Homo Estás?”) sometimes makes the parades feel like pep rallies for our roles as mere consumers rather than fierce, proud members of a subculture. Sure, that subculture status is probably fading as we find more and more allies, but as our Twitter feeds and Facebook walls showed after the Caitlyn Jenner story broke, we still have a long way to go teaching ourselves and others about the complexities of our communities.

For those privileged enough to attend one of the many parades and festivals this month, the concept of Pride serves a reminder that, despite our oft-immense feelings of isolation, we aren’t alone in our experiences. Even though we were born into a world not quite made for us, we queer people have carved out a place in it for ourselves. That place isn’t a utopia; the issues of gay men still dominate the movement’s attention at the expense of our greatly diverse queer communities. Furthermore, Pride should also be about more than our gay dance parties, no matter how great the playlists we create for them. The feel-good notion of Pride is tampered by the growing violence against trans bodies and our communities’ collective neglect of LGBT homeless and seniors. (See DarkMatter’s #NotProud conversation on twitter).

As our concept of Pride changes, so should our priorities. We can welcome Chipotle, but Pride also comes with a responsibility to better our communities, to educate, and to help others. The rainbows on vodka bottles and burrito wrappers are signs of our greater acceptance, but they are the result of the tireless work of homophile activists and liberationists, people who braved jail and shed blood so that we might be able to fight about what the heck pride is all about generations later. We owe it to them and to ourselves to make Pride both a party and a time to reexamine our queer sensibilities.

Happy Pride.

Gay Pride “Kings and Queens 3,” 1989. Photograph by Joyce Culver. Photo courtesy The Museum at FIT

Queering the Indy 500

BY Eric Gonzaba ON May 24, 2015

That’s right. I’m attempting the impossible. I’m going to suggest that there is something queer about the Indy 500. Any event that brings in a viewership of nearly six million people is bound to be a little gay, right?

That’s right. I’m attempting the impossible. I’m going to suggest that there is something queer about the Indy 500. Any event that brings in a viewership of nearly six million people is bound to be a little gay, right?

If you’re not familiar, the Indianapolis 500 is a car race that takes place every May in Speedway, Indiana, just outside the state capital of Indianapolis. The speedway itself is arguably the largest arena in the world, with a seating capacity of more than 400,000. To give you some perspective, that’s five times the seating capacity of the Dallas Cowboys’ stadium. Point being: the 500 is a big deal, not just for Hoosiers, but to lots of racing fans.

But is there really anything gay about the Indy 500? After all, the race has no halftime show like during the Superbowl to relieve gay men from the boredom of football with the likes of Beyonce or Katy Perry, even if just for a painfully short ten minute set. Ok, I’m being extremely stereotypical, but people buy into these stereotypes, that all queer people live by a set standard of likes and dislikes, that we all bow to the gods of urbanism, pop, and liberalism.

As important as it is to find and identify the unique sites of our LGBT communities (the underground urban discos, the disappearing feminist bookstores, the black fraternities, the vogue balls etc.), it’s quite extraordinary to discover the ways queer communities in the past sought to both integrate and remake mainstream cultural events and sites like the Indy 500.

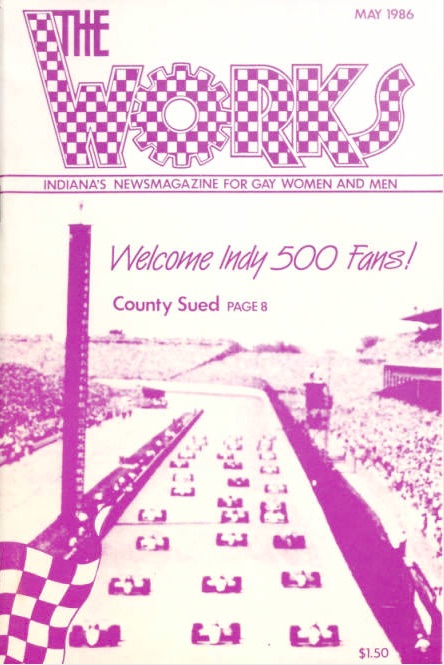

Looking through Indianapolis gay magazines of the past 30 years, it’s incredible to see the warm welcome of gay fans to the racing capital. The entire cover of the May 1986 issue of Indiana’s gay newsmagazine The Works was a greeting message to out of town gay racing fans. As one queer commentator put it, “Hope to see all you fags up in Indy this month to ‘see’ the 500 race,” probably in reference to either the quickness of the Indy racecars or perhaps the draw of gay men to other, non race events in May. Either way, the race meant at least something to Indy’s gay community.

Throughout the 1980s, Indianapolis’ queer community used the race and its out of town gay fans as a reason to congregate and party. Indianapolis’ gay bars hosted race-themed disco dances, complete with drag queen contests like the “Club 500 Queen” or the “Speedway Housewives” as well as the “500 Follies.” Disco divas like Linda Clifford were brought in to entertain fans over the qualification weekends and the famous race day.

Hardcore race fans could watch the races and local bars and clubs during special barbecue cookouts. A 1984 gay writer suggested that though latecomer gay race fans probably couldn’t get grandstand seats on the last weekend before race day, infield tickets were still on sale. “If you thought the Romans had orgies,” the columnists wrote, “try the infield!”

Even the race’s longtime traditions have a queer angle. For over forty years, Jim Nabors of Gomer Pyle fame sang “Back Home Again in Indiana” just before the race to the delight of adoring race fans. In 2013, Nabors married his longtime partner of nearly forty years, Stan Cadwallader. Granted, Nabors’ sexuality remains largely unknown to many Speedway fans but this didn’t stop the infamous Westboro Baptist Church from protesting the event in 2014 (Nabors’ last singing appearance), with the hate group citing Nabors’ homosexuality as one of their main grievances. Regardless of the Westboro morons, I cannot help to think how ironic it is that a state marred in scandal the past few months over allegations of anti-gay discrimination and religious freedom could let a gay man become so attached to a time honored Hoosier tradition.

Today’s racing fans don’t have to look very far to find likeminded compadres. In recent years, a dedicated queer racing community has sprung up online. Sites like Queers4Gears serve as resources for dedicated gay Indy and NASCAR racing fans, offering visitors “gaynalyses” as opposed to traditional, yawn-inducing coverage on conventional news platforms. Queers4Gears founder Michael Myers presents balanced reporting on races, but his queer perspective means a new vocabulary fit for his gay audience, sometimes, for example, referring to drivers as “divas.”

Maybe it’s not important whether or not there is a queer history of the Indy 500. Maybe we should just leave the pit stop and investigate how LGBT people are not always separatists but sometimes active definers of wider, normative culture. The 500 is one reminder that our unique queer perspectives can penetrate even the most “redneck” of institutions.

Indiana: A Pizza Work

BY Eric Gonzaba ON April 13, 2015

First off, I’m a Hoosier. Sure, an adopted one (my last name is Gonzaba, after all), but a Hoosier nonetheless. I lived in Indiana for a decade beginning in 2003 and true to form, I’ve eaten my share of popcorn, attended my county fair’s demolition derbies, marched in my small town high school’s marching band, and graduated from the largest public university in the state; Go IU.

First off, I’m a Hoosier. Sure, an adopted one (my last name is Gonzaba, after all), but a Hoosier nonetheless. I lived in Indiana for a decade beginning in 2003 and true to form, I’ve eaten my share of popcorn, attended my county fair’s demolition derbies, marched in my small town high school’s marching band, and graduated from the largest public university in the state; Go IU.

I’ve never eaten at Memories Pizza, though. This is partly because the restaurant is in Walkerton, Indiana, and even as a Hoosier, I had never heard of Walkerton, Indiana. There exists this cultural divide among southern and northern Hoosiers and Walkerton is “way up north” as my southern Corydon brethren would say. I’m not kidding about folks from Indiana taking serious pride in their northern or southern status. When I first moved to the state, a gas station attendant asked where my family was from, to which I replied “Texas.” “Ah,” she exclaimed, “you’re in the REAL South now.” I was, and remain, confused.

If you’re not familiar, Memories is a small pizza parlor that became famous a few weeks ago during the national outrage that erupted after Indiana’s passage of the so-called Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). One of the owners of Memories Pizza told a local reporter that her business would not cater a gay wedding if it ever came to it, though gays and lesbians were still welcome to dine in her establishment. Enter the Internet and what it does best—the restaurant was lambasted on Yelp by fake reviews, one who noted that “the food tastes like hate.” Supporters rushed to Memories’ defense and raised over $800,000 in donations to the small business.

There are so many ways to parse the situation in Indiana last month, and being a Hoosier only complicates the matter. On one hand, it’s easy to see how one could be ashamed of their state. How is it that a people could be so intolerant? On another, Hoosiers aren’t New Yorkers, and they pride themselves as such. They are products of outsiders seeing them as backwards and simple people. Even if you thought Indiana’s RFRA was despicable (and you really should, by the way), comments from pop cultural icons like George Takei seemed misplaced. Boycott Indiana? Sure, I understand and appreciate strategies of slash and burn, but were you ever really going to come to Indiana in the first place, much less care about its people? If the answer was yes, does your notion of Indiana reach past the ten-block radius of progressive, urban downtown Indianapolis?

The Memories Pizza incident is another battle of America’s ongoing culture war. No, not the one Bill O’Reilly tries to convince his viewers is about life and death or liberty and tyranny. I like to think of the culture war as a series of contestations between differing values. These incidents are heightened by the fact that America is a diverse place. Her people are divided along religious, generational, racial, gendered, and, most prominently here, geographic lines. For LGBT Americans, these battles are all too familiar: the campaigns of Anita Bryant, a children’s book about gay penguins, the battered controversy over Chick-fil-A. These matters often appear trivial, but they irk so many because they appear to threaten the most matter-of-fact aspects of our lives (the restaurants where we eat, the books our children read).

I don’t want to suggest that our LGBT communities shouldn’t be outraged at Memories. Our communities should fight discrimination wherever they see it, but in the digital age, I’m starting to think that these battles in the culture wars are becoming too easy. It’s too easy to be appalled from behind the safety of our computer screens, to share one’s shame of being from backwards Indiana or to rally behind a homophobic business with your credit card.

We ought not be discouraged that a million dollars can be raised for some business that doesn’t want to cater gay weddings. Rather, like so many opponents of RFRA did in the last few weeks, we need to remain vigilant of laws that only serve to oppress. Furthermore, it’s on us to not always be reactionaries. LGBT and allied communities should meet these challenges before they come to fruition. If there is a silver lining in any of this, it’s that democracy worked in Indiana. National outcry led to a change in the law, and Hoosier businesses cannot use RFRA as a defense for refusing to serve gay people pizza. Granted, it’s not enough (Indiana needs an anti-discrimination law that protects sexual orientation and gender identity), but it’s a start. We can relax tonight and have a slice, just not at Memories.

The Coming Gay Conservative Revolution

BY Eric Gonzaba ON March 23, 2015

Photo by Mario Piperni

I joke with some of my friends that soon, especially with what seems like the inevitable embrace nationwide of same-sex marriage, gay men will be flocking to the Republican Party, eager to distance themselves from gay activism or stereotypes as lefties, eager to act like their gay identity doesn’t tie themselves to a certain political ideology. I say joke, but I do think there’s something to be said that the end of the gay marriage debate might bring about an end to bringing national attention to LGBT issues, and with that, reassurance within our own queer communities that we have attained equality and are now living in a just society.

Gay marriage is a partisan issue and with that, LGBT people have largely united as a voting bloc against the conservative American political party. Self-identified LGBT Americans overwhelmingly voted for the reelection of Barack Obama (some 77% in support). That’s about 7% more than gay support to McCain, who, unlike Romney, did NOT support a federal amendment banning gay marriage. So why do I suspect there’ll be a conservative resurgence in our communities (but, most especially, among gay men)? Am I just some crazy skeptic, like Republicans who think global warming isn’t real because it snowed this winter?

No, I say this because advocating for marriage is, lest I sound like a “Mean Girl,” so0o0o0o0o conservative. Ask them yourselves—conservative gay columnists like Andrew Sullivan have argued as early as the 1980s that the Right should embrace gay marriage. They say, despite our communities’ transgressive roots, “a need to rebel has quietly ceded to a desire to belong. To be gay and to be bourgeois no longer seems such an absurd proposition.”

That, in fact, is part of the problem. Is our community really challenging “common assumptions and core institutions,” as John D’Emilio put it in a recent OutHistory post? This conflation of marriage equality as the main indication of LGBT progress has remade gay politics from being about class, gender, racial, and sexual liberation to one about money and societal comfort.

In Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (Duke, 2007), Jasbir Puar discusses how the American gay community has sought integration and political rights through consumerism, exuding patriotism by doing what Americans do best—spending! Take, for instance, how the gay community is targeted by the tourism industry. After all, who better to target for travel to than the gay male, who, as the stereotypes tell us, is rich, educated, and without pesky children. In other words, they are prime consumers. As Alexandra Chasin suggests, gays and lesbians are bombarded by advertising that suggests their spending would eventually bring about their “full inclusion in the national community of Americans.”

This is nothing new for a social movement. In the past century, several disenfranchised groups, especially African Americans, sought progress not just by appealing to morality or political rights (the right to vote, hold office, etc.), but through consumption. They found a route to political success by appealing to economic freedom, the right to sit at a lunch counter or to buy a new washing machine at a segregated store. However, there is something extremely insidious about our embrace of a gay politics centered on spending and the conservative message that “we are just like everyone else.” If we are to believe the tourism industry, gay politics is all about being white and rich, which in turn means there is little demand to address the needs of racial minorities or those with lower socioeconomic status. It also produces an excuse for normative society to exclude sexual orientation as a suspect class in need of protection.

I’m not saying that you LGBT Americans can’t be conservatives. Everyone is allowed to believe what he or she wants (Senator Inhofe and his snowball on the Senate floor trying to debunk immense scientific consensus on climate change, is a great example that Americans really do have that freedom.) I also think you’re allowed to “care more about the economy and our nation’s security more than [you] do the government recognizing [your] relationship with someone,” as one young gay conservative told the Blaze last year.

While this divide is certainly problematic (I feel like Democrats probably care about national security too), LGBT communities certainly can turn Right if it aligns with their interests, though we should probably ask ourselves why so many don’t. Look at those enlightening (if not tangential) roundtables with black conservatives on Sean Hannity’s Fox show. While it’s great to give a forum to people with different viewpoints, one has to wonder why 90% of African Americans vote Democratic. It’s certainly not, as conservatives say, just that they’re pawns of the Democratic party; after all, Democrats have lost 3 of the last 4 midterm elections, certainly not indicative of a superb mind-control operation.

So yes: perhaps the emergence of a society okay with gay marriage will mean an end to an LGBT coalition. However, as a wider community, we ought to consider whether queer factions should want to leave such a political union. Even if we don’t want to be the radicals we once were (and we certainly should rethink that), we owe it to our progressive allies in any political party (Democrat, Republican, Green, Libertarian, or gasp!—Communist) to continue our aim at a more egalitarian society.

Defiance in Dixie

BY Eric Gonzaba ON March 9, 2015

I wanted to spare readers yet another post on gay marriage, perhaps the most exhausted of topics written by and about LGBT communities. I figure we will all get our fill about the issue in the next few months as the U.S. Supreme Court is finally set to hear oral arguments on April 28th. I’m also fully aware about how problematic it is to focus on the issue of gay marriage (see Dan Royles excellent discussion about queer politics and Ferguson) That said, with all the mess same-sex marriage has caused in Alabama over the last few weeks, I couldn’t resist.

I wanted to spare readers yet another post on gay marriage, perhaps the most exhausted of topics written by and about LGBT communities. I figure we will all get our fill about the issue in the next few months as the U.S. Supreme Court is finally set to hear oral arguments on April 28th. I’m also fully aware about how problematic it is to focus on the issue of gay marriage (see Dan Royles excellent discussion about queer politics and Ferguson) That said, with all the mess same-sex marriage has caused in Alabama over the last few weeks, I couldn’t resist.

No, this won’t be a post where I try to convince you that gay marriage should be legalized. There are far too many eloquent writers who’ve already done that, and more importantly, far too many anti-gay marriage folk who’ve made it easier for those writers. (I’m looking at you, Dr. Ben Carson, who said this week that prison makes you gay.)

I wanted to focus on Alabama, which was ordered to begin granting marriage licenses to same-sex couples early last month following a ruling by a Federal District court judge. Unlike most states in similar situations that complied with federal rulings, Alabama’s deeply religious Chief Justice Roy Moore ordered probate judges to not grant marriage licenses. Probate judges split on the matter; some stood by their Chief Justice while others bowed to federal authority. All this became moot just a few days ago, however, after the Alabama Supreme Court (headed by Chief Justice Moore) halted all same-sex marriages in the state. Despite a tide of same-sex marriage acceptance nationwide, Moore and Alabama are prepared to take a stand.

It might be expected that same-sex marriage wasn’t going to go as smoothly in the state as it had in other parts of the country. After all, only 1 in 5 Alabamians approve of same-sex marriage (the state ranks 49th in the country. Your guess for #50 is probably correct). But the fight for marriage rights in Alabama was surprisingly civil. Despite some rare testy exchanges with protesters outside of county courthouses, news footage documented long waits for couples who waited to hear if their local probate judge would offer them a marriage application. Some were sustained, they said, by the kindness of strangers who brought them fast food during their day-long waits at the county offices, unwilling to miss being present in case any news trickled in. When Etowah County, far from the urban centers of Montgomery or Birmingham, opened their marriage windows, a lesbian couple remarked that the clerks were professional and courteous and “on their game.”

As of now, though, those windows remain closed to same-sex couples. The most frustrating thing about this whole fiasco is Chief Justice Moore himself. For over a generation now, the Deep South has been fighting the legacy of Jim Crow and segregation. Alabama and Mississippi (your guess as to #50) were the heart of white southern resistance during the black freedom struggle, and since then, outsiders have viewed them as the true racists of American society. Places like Alabama and Mississippi became what historian Joseph Crespino call “metaphor states,” sites the nation as a whole can point to as the genuine holders of racial and discriminatory animus, as if the rest of the nation is innocent of gross civil rights issues. For example, why does New York City, a beacon of gay tolerance we’re told, refuse to address rising LGBT homelessness. In terms of homophobia, the south is by no means exceptional.

To be sure, this doesn’t mean Alabama is off the hook. Alabama deserves our national anger. The legacy of lynching, voting disenfranchisement, peonage, slavery, and unethical medical experiments, to name just a few, is still very much real.

But Chief Justice Moore’s actions is so vividly reminiscent of Alabama Governor George Wallace’s famous stand in the schoolhouse door at the University of Alabama to protest desegregation in 1963. What’s mind boggling is that Moore is no dummy; he attended the U.S Military Academy and the prestigious, highly ranked law school at the University of Alabama. He’s fully aware of his home state’s tarnished racial legacy and yet still felt compelled to defy federal rulings on a monumental civil rights issue, which he opposed largely on religious grounds.

Now, I’m somewhat uncomfortable with the conflation of the black civil rights movement and the LGBT rights movement (the “new civil rights movement,” as some call themselves). Yet, Moore’s actions more easily merge the movements in the minds of the public. By doing so, it’s another anchor to pull down Alabama’s chances of ever really not being one of the focal points of national disgrace.

Maybe Alabama wasn’t going to be able to shed it’s racist label anytime soon, but Chief Justice Moore, a man overwhelming supported by his constituents, single handedly contributed to the state’s intolerant image. Like Wallace, I doubt history will be kind to him. Hopefully though, future historians will even care more about the clerks who opened their windows, the eager couples in line, and the vibrant queer communities of the South than they do about a cowardly Chief Justice.

Homophobia Isn’t Black

BY Eric Gonzaba ON February 23, 2015

I remember being in college when, at 11pm on November 4, 2008, news networks announced the election of the first Black American president. The new president-elect even gave the LGBT community a shout-out in his acceptance speech that night, which was fitting since 70% of the gay community had supported him in that election.

I remember being in college when, at 11pm on November 4, 2008, news networks announced the election of the first Black American president. The new president-elect even gave the LGBT community a shout-out in his acceptance speech that night, which was fitting since 70% of the gay community had supported him in that election.

Not too long after that, however, those same news outlets reported that Proposition 8 passed in California, barring same-sex marriage in the nation’s most populous state. It was stunning to many LGBT activists, since polls looked good going into Election Day. What went wrong? Pundits pointed to the immense turnout of black voters in California. 70% of African Americans helped land the first black president into the Oval Office and simultaneously voted to keep gay people away from the wedding chapels. See, the blacks are to blame! Sigh…the downfalls of supporting a coalition party.

It didn’t take long for more reasoned minds to explain that African Americans weren’t solely to blame for Proposition 8’s passage. As statistician Holy One Nate Silver pointed out, “ Prop 8’s passage was more a generational matter than a racial one.” Ta-Nehisi Coates was rightly more angered, lambasting political pundits and news outlets for citing overblown statistics; the 70% of African Americans number was probably closer to 58%.

I use this Prop 8 story because I think it suggests that liberal Americans are often too ready to attack black communities as anti-gay. We need to be much more conscious about how diverse communities confront LGBT experiences before we so-readily judge the gay-friendliness of certain groups. Our biases toward/against black culture can often shield us from understanding how diverse queer culture is in the African American community.

We’re told that black gay men, for instance, stay on the down low, afraid to embrace the rapidly changing, queer accepting, modern culture. Recently, however, excellent works have been produced that show that this stereotypical portrait of an exclusively heterosexual-affirming black culture is a fantasy at best. Take Terrance Dean’s 2008 memoir Hiding in Hip Hop: On the Down Low in the Entertainment Industry. The book’s cover photo depicts an African American artist holding his finger to his lips, insinuating the man is trying to keep something quiet. But Dean doesn’t suggest black American communities are terrifying places for LGBT people. In a discussion of his book with TIME magazine, Dean talked about down low culture for black men where there exist three identifications: down-low, down-low gay, and gay.

“What I consider to be in the closet is someone who I would call a down-low gay man. A down-low man is a man who considers himself a bisexual. He has relationships with both men and women but he would never identify his sexuality as that of a gay man because he doesn’t see the act of what he’s doing as that of being gay. Most times he is the penetrator or he’s the receiver in oral sex. So he doesn’t see himself as being gay. If you ask him, he would never admit to being gay.”

Of course, this is Dean’s assessment of his gay world, but the diversity of the identities he describes is a far cry from how many Americans think of sexual orientations, where we all fit neatly into predefined categories of gay or straight. Bisexuals, we hear all the time, just need to pick a team. (Tell this to Oregon’s new governor).

Dean’s discussion reminds me of historian George Chauncey’s work on early 20th century gay male culture. Chauncey argued that working class men in the early 20th century could engage in diverse sexual practices, including with other men, without necessarily being considered queer. Men who assumed the traditional sex role for men, even if their partner was another man, were not necessarily considered homosexuals by the wider society. In fact, such an act might enhance a man’s masculinity. “Sexual penetration,” Chauncey wrote, “symbolized one man’s power over another.”

Dean’s take on black sexual identities brings Chauncey’s discoveries into the 21st century and complicates our collective understanding of the homosexual/heterosexual binary. To be sure, the down low culture can breed social stigma of queer people in the black community and be cause for deep anxiety for LGBT black people. There’s no denying that homophobia exists in the African American community, but it’s not simply a problem that is inherently tied to black identity; homophobia is systemic, reaching beyond class, race, gender, and national boundaries.

So tying blackness to homophobia is too reductive, but we also need to stop thinking of LGBT life as uniform among diverse communities. Historians have shed light on how gay identity hasn’t always been a central feature of African American lives. Take the American South, a place I’m sure many Americans would be surprised to know does actually have an LGBT history (and quite a rich one at that.) Historian John Howard, for instance, argued that black men in the south often viewed 20th century LGBT activism with suspicion, part of yet another “white-controlled, white dominated institution.” Terms like gay don’t always sum up the diverse experiences of Southern queer people. Read any of the incredible oral histories in E. Patrick Johnson’s Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South and you’ll discover that black queer life has flourished even in what we sometimes target as the most hostile of places to LGBT African Americans—the black church. To the contrary, the church sometimes has served as a site of negotiation for African Americans, a place where spirituality and sexual desire can be explored and where black gay men can search for affirmation.

All this is to say, I think it’s imperative for us not to simply jump on the bandwagon of saying African American culture is homophobic by nature. Instead, we ought to be understanding of the diverse ways queerness is expressed in the black community and acknowledge that perhaps these practices can’t be readily understood through societal lenses that, more often than not, are heteronormative and white. The queer culture of people of color may not look like what’s shown in HRC commercials or on mainstream television sitcoms, but it’s a more dynamic culture that it is given credit for.

A Presidential Drag Race

BY Eric Gonzaba ON February 11, 2015

Going through the over 200 t-shirts I recently digitized at Chicago’s Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, I came across a t-shirt that pictured a drag queen recruiting supporters for a presidential campaign in the style of Uncle Sam: “I Want You, Honey.” I had to look into this woman.

Going through the over 200 t-shirts I recently digitized at Chicago’s Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, I came across a t-shirt that pictured a drag queen recruiting supporters for a presidential campaign in the style of Uncle Sam: “I Want You, Honey.” I had to look into this woman.

Joan Jett Blakk, a Detroit-born Chicago drag performer, made quite a stir in the early 1990s running both for Mayor of Chicago and President of the United States. Blakk helped found the Chicago chapter of Queer Nation, a political group aimed at educating the public on queer issues at the height of the AIDS crisis. Blakk’s outlandish style and eagerness to throw herself into mainstream political campaigns raised eyebrows and brought attention to queer issues, even if more conservative, accommodationist gay circles thought Queer Nation too militant and “in your face.”