In the Archives | Go Out and Interview Someone! The Robinn Dupree Papers

BY John D'Emilio ON November 30, 2016

Our life stories are the core content of LGBT history. Yes, our organizations and businesses produce records that detail important work. And mainstream institutions and social structures affect us deeply. But the texture and the challenges of what it means to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender at different times and in different places will only fully emerge if we make an effort to collect a broad range of our life stories. Reading – or hearing – the life story of an individual is not only compelling and absorbing in its own right. It can also open doors of understanding and offer revealing insights into what it was like to be . . . well, whatever combination of identities the individual brings to the interview. Each of our life stories will have something to tell us beyond the L,G,B, or T. We are also the products of regional culture, of racial and ethnic identity, of religious upbringing, of our particular family life, of class background, of work environments, and other matters as well.

The truth of this was brought home to me when I stumbled upon the small box of papers at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives labeled “Robinn Dupree.” In November 1996, a professor in folk studies at Western Kentucky University took his class of graduate students to Nashville to see a performance of female impersonators at a bar, The Connection. One of those students, Erin Roth, was so impressed by the event and by the lead performer, Robinn Dupree, that she asked for permission not to do her seminar paper on the assigned project – interviews/studies of “riverboat captains and old-time musicians” – but instead be allowed to interview Dupree and write about the art of female impersonation. The professor said yes, and so Roth conducted two interviews with Dupree, in March and April 1997. Fortunately for everyone else, she donated the tapes, a typed transcript, and her seminar paper to Gerber/Hart, so that Dupree’s account of her life is now available for study and inclusion in our collective history.

To summarize her story briefly: Dupree was born in 1952 in Chicago, her mother of Sicilian background and her father a Puerto Rican of African heritage. When she was in the 8th grade, she told her mother she was gay. As a teenager, she discovered the Baton Show Lounge, run by Jim Flint and already well-known for its performances by female impersonators. Soon she was sneaking out of the house to go there regularly. “It’s like I found what I wanted to do,” she told Roth, and soon Flint was coaching her and she began performing regularly.

Dupree performed at the Baton for almost a decade, and then moved on to another club, La Cage. In 1982, her boyfriend of ten years, who had connections to the Mafia, was killed in a car bombing outside their apartment building. Dupree realized it would be best to leave Chicago quickly, and she resettled in Louisville, Kentucky, where she rapidly made her way into the local female impersonator scene. Over the next decades, she performed for long stretches in Louisville, Nashville, and Indianapolis. According to online sources, her last show before retiring as a performer was just a few months ago, on February 13, 2016.

Reading the transcript of the interviews as well as Roth’s paper, I was struck by certain themes, some of which likely have broad applicability and some of which might be particular to Dupree. One involves economics. For those like Dupree who take the work of impersonation seriously as an art form and devote themselves to it, the economic realities can be harsh. On one hand, costs are high: the dresses, the jewelry, and everything else associated with the glamor of their performance are expensive, and new apparel has to be bought regularly for new shows. On the other hand, wages are low. Performers depend on tips, but these are unpredictable and often will not support them sufficiently. Thus, most impersonators need to have a day job, but that brings them up against the gender boundaries of the culture.

Another theme is family. As Dupree became a well-known, successful, and seasoned performer, younger impersonators-to-be came to her for advice, tutoring, and support, just as she had received from Jim Flint when she was starting and barely out of her teens. To many, she was their “mother,” and to Dupree, they were her “daughters.” The terms conjure up images of a warm and intimate family of choice, which it is. But behind the pull to use those terms is a harsh reality. After Dupree started performing, her biological mother broke off contact with her, and they remained separated for ten years. “Most people who do drag or want to become women, their family totally disowns them,” Dupree told Roth in their interview. Although Dupree acknowledged that much had changed in the 25-plus years since she had started performing, the loss of connection to families of origin remains true for many. Thus the relationships that were established had significant emotional and practical meaning. Dupree’s daughters often lived with her for long stretches as they worked to establish a life for themselves. Yes, it was a chosen family, but it was also a deeply needed family.

A third issue emerged in reading the interview with Dupree: the complexities and shadings of identity. At the time of the interview, in 1997, transgender had just recently established itself as a term of preference in the LGBT movement and in activist circles. Dupree described herself as “a pre-operative transsexual . . . I live every day of my life as a woman.” She had had surgeries done on her face to accentuate a kind of feminine beauty. She had also done hormone treatments in order to increase her believability as a performer in the world of female impersonation. “That’s why I actually ended up taking hormones and becoming a pre-op,” she told Roth. “Not to become a woman, but to look as much like a woman on stage as possible.” And within this world of stage performance, at least in the decades in which Dupree was an important presence, a range of self-understandings existed. “I have some daughters who want to be just entertainers. Then I have other daughters who want to go all the way through and become a woman.”

The Dupree oral history at Gerber/Hart is a treasure. We need more of them. Go out and interview someone – now!

LGBT History: Dramatically Expanding

BY James Waller ON November 25, 2014

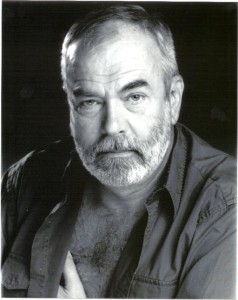

Arch Brown, who established a foundation in honor of his partner Bruce. to fund queer history through theater

When my friend Arch Brown established the Arch and Bruce Brown Foundation some 20 years ago, I was delighted to be asked to serve on the organization’s board, but I’ve got to admit I was a little concerned about its mission. I thought that by focusing on literary and performing arts work “based on, or inspired by” LGBT history, Arch might be drawing too tight a boundary around the kinds of things the foundation could fund. It wasn’t that I wasn’t interested in queer history—I shared that enthusiasm with Arch and his then recently deceased partner, Bruce Brown, to whose memory the foundation was dedicated. I was just afraid that the literary competition and play production grant program Arch envisioned wouldn’t draw enough submissions, because of that “historical” restriction.

Our early literary competitions—back then, we alternated yearly between plays, novels, and short stories—drew 20 or 30 or 40-some entries, and, frankly, I kept expecting this stream to run dry. I just couldn’t imagine that there were all that many fiction writers and playwrights “out there” who were (1) writing about LGBT people and (2) basing their work on historical sources. What a failure of imagination on my part. Over two decades, the stream has turned into a torrent. The foundation’s 2014 playwriting competition (our annual contest is now restricted to plays) drew a whopping 254 entries. Now, granted, some of the plays submitted were ineligible for consideration because they made only glancing reference to history (if any reference at all)—but there were relatively few of those. This flood of competition submissions—combined with all the grant proposals we’re getting that seek support for new performing-arts works based on LGBT history—convinces me that a formidable, and growing, number of LGBT artists are looking to history for inspiration.

And to judge from our competition and grant-program submissions, the parameters of LGBT history also seem to be expanding dramatically (pun intended). Sure, we still receive plays (and requests to fund plays) about notable historical personages. Michelangelo is a perennial favorite, unsurprisingly, and this has been a bumper year for works about Alan Turing. Nothing wrong with that, and, in fact, some of these works are quite good: Among the runners-up in our 2014 play contest was Michelangelo and Tommaso, by Sacramento-based writer James Rosenfield, which centers on the young Roman nobleman with whom the artist was reportedly infatuated. And a highly inventive, intellectually dense theatrical work about Alan Turing, called Pure and written by Queens, New York–based writer A. Rey Pamatmat, won one of our honorable mention awards this year. (We’ve also recently helped fund a new opera based on Turing’s life being produced by the American Lyric Theater, as well as a documentary film about controversy over the posthumous royal pardon Queen Elizabeth granted Turing a year ago.)

But alongside works like these come entries set in unexpected locales with casts of characters very unlike those we used to see. This year’s competition winner, The Dangerous House of Pretty Mbane, by another Queens-based writer, Jen Silverman, is set largely in South Africa against the backdrop of the 2010 World Cup; its characters, with one exception, are black South Africans. Centering on a young woman’s search for her vanished former lover, a lesbian activist fighting the heinous practice of “corrective rape,” the play is rooted squarely in recent South African history. About its genesis, Silverman told me, “My inspiration was an actual petition circulated by a woman named Ndumie Funda, of the activist organization Luleke Sizwe. The petition called for corrective rape to be recognized as a hate crime, [and] I was captivated by the idea of someone putting herself in the national eye, putting herself at such risk at home.” An emotionally devastating, morally complex work that even dares explore the all-too-human motivations of one hate-crime accomplice, Dangerous House will have its premiere production at Philadelphia’s InterAct Theatre in January.

Nearly contemporaneous but worlds away from Dangerous House are the setting and characters of one of this year’s second-prize winners (two plays tied for second place this year). That play, Average American, by Manhattan-based writer Susan Miller, is a behind-the-scenes, often comic look at the development of the first-ever American TV program about lesbian women. A fictional account based loosely on the making of the pilot for Showtime’s The L Word, on which Miller worked, Average American serves up a very different but undeniably important slice of LGBT history. As Miller told me, “People are hungry to see themselves. Shining a mainstream light on the lives of gay people, women especially, marked a turning point in the public exploration of LGBT identity and representation. We made history.”

Our other second prize went to the play Mr. and Mister, by Robert Matson, who lives in Edmond, Oklahoma, and who, with his partner, has run a gay community theater in Oklahoma City for the past 15 years. Its setting is more formulaically “historical”: the action takes place on the Great Plains during the post–Civil War years. But it, too, breaks new ground in the exploration of the LGBT past by powerfully depicting the intersection of multiple histories of oppression in the United States—of gay people, African Americans, Native Americans, and those who seek love or employment outside a socially accepted norm.

So I’m very happy to report that I was very wrong, 20 years ago, to be worried about our little foundation’s mission. The bounds of LGBT history are just as wide, its complexities just as deep, as those of human history itself—and the possible uses of that history are, for creative artists, apparently inexhaustible.

James Waller is a writer and editor and a regular blogger and contributor to mediander.com. Since 2012, he has served as president of the Arch and Bruce Brown Foundation.

News and Announcements

BY Claire Potter ON November 2, 2014

- The LGBT Resource Center at the University of California-San Diego is celebrating its 15 year anniversary with a November 7 symposium, “We Cannot Live Without Our Lives: A Conversation on Anti-blackness, Trans Resistance and Prison Abolition.” Go here for more information, as well as a list of other exciting events and conferences being held throughout the state in 2014-2015.

- The Committee on Lesbian and Gay Studies (CLAGS) at the City University of New York presents Rough Around the Edges: Peggy Shaw in Conversation, Tuesday, November 4th 2014, 7.00-9.00pm, at Segal Theatre, The Graduate Center, CUNY. Shaw, a founder of Split Britches, a downtown New York lesbian theater troupe, will expand upon how her past inflects her current performance work, both solo and collaborative, and will reflect upon her four decade career on the experimental stage. Go here to make a reservation.

And have you seen….

- Black & Gay in Black and White, one of the first exhibits to document the contributions of Boston’s African American GLBT community, created at Northeastern University in October of 1997?

- The Dykes on Bikes Exhibit Tour with Glenne McElhinney, courtesy of San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society? Enjoy!