In the Archives | Artemis Singers

BY John D'Emilio ON June 7, 2017

As someone who is not particularly musical, thinking about the place of music and performance in history poses challenges. Certainly music has played an important role at various moments. No one would dispute, for instance, the importance of music in the civil rights movement and in white youth culture and protest in the 1960s. But, how does one evaluate its impact? How does it fit into the chronicle of a movement? How does it foster change in other spheres of society?

As someone who is not particularly musical, thinking about the place of music and performance in history poses challenges. Certainly music has played an important role at various moments. No one would dispute, for instance, the importance of music in the civil rights movement and in white youth culture and protest in the 1960s. But, how does one evaluate its impact? How does it fit into the chronicle of a movement? How does it foster change in other spheres of society?

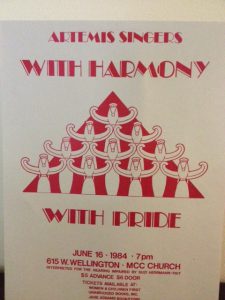

If you are interested in music and the place it deserves in writing history, then the papers of the Artemis Singers at the Gerber/Hart Library offer opportunities to explore this topic. Artemis was a self-consciously lesbian chorus. It saw itself as “an educational political vehicle for changing negative stereotypes about lesbians.” At the time when it formed in the summer of 1980, a world of women’s music was growing rapidly. Women’s music festivals were sprouting up around the country and there were at least a couple of dozen all women and openly feminist choral groups. Yet, as Susan Schleef, the founding director of Artemis, noted, among these groups in the early 1980s there was only one other self-declared lesbian chorus. Schleef and the members of Artemis intended to create more visibility for lesbians in this cultural environment, especially because music events across the United States were becoming public spaces of feminist solidarity. Artemis jumped right into this world, joining the recently founded Sister Singers Network, which kept these choruses in communication with each other and coordinated the planning of major events. Schleef and other Artemis members participated in the first Midwest Women’s Music Festival, held in the Ozarks in 1982, and helped make it into an annual event in the 1980s.

Besides its work in the thriving milieu of women’s music, Artemis also thrust itself into the newly emerging world of gay choral performance. In Chicago in 1979, two musical groups had formed, the Windy City Gay Chorus and the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Community Band, and they were beginning to perform at major events like the annual Pride March and Festival. An umbrella group, Toddlin’ Town Performing Arts, was created to provide nonprofit status and allow money to be raised to support the groups. Artemis became the third member of Toddlin’ Town and provided a lesbian presence at its meetings, where performances and other events were planned. At the time Artemis joined, the board of directors was entirely male and there was, in the words of one Artemis member, a “tendency towards mutual suspicion between lesbians and gay men.”

In 1983, the relatively young network of LGBT choral societies took a big leap forward into visibility. The first “National Gay Choral Festival” was scheduled for September, to be held in Manhattan at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, as prestigious a cultural venue as existed in the U.S. Almost 700 singers from 11 choruses performed at the Festival. Artemis was the only group of women. “Come Out and Sing Together,” as the festival was titled, stretched out over three days. At a time when AIDS was beginning to ravage the world of gay and bisexual men in large American cities, and when media coverage strengthened the most negative stereotypes of homosexuality, the choral festival provided a much-needed counterpoint. By 1986, when a second national choral festival was held, “women’s participation had increased five-fold,” according to a report in the Artemis Papers.

In 1983, the relatively young network of LGBT choral societies took a big leap forward into visibility. The first “National Gay Choral Festival” was scheduled for September, to be held in Manhattan at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, as prestigious a cultural venue as existed in the U.S. Almost 700 singers from 11 choruses performed at the Festival. Artemis was the only group of women. “Come Out and Sing Together,” as the festival was titled, stretched out over three days. At a time when AIDS was beginning to ravage the world of gay and bisexual men in large American cities, and when media coverage strengthened the most negative stereotypes of homosexuality, the choral festival provided a much-needed counterpoint. By 1986, when a second national choral festival was held, “women’s participation had increased five-fold,” according to a report in the Artemis Papers.

The work of Artemis, as well as that of other lesbian choruses that sprang up in these years, did have an impact on the gender dynamics of these musical networks. Testimonials from a national conference of GALA (the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses) held in Minneapolis in 1986 document the progress. “I went to Minneapolis with more than a slight case of negativity,” one lesbian wrote afterward. “I had prepared myself to grin and bear it . . . Never did I dream that I would come to feel such a close and compassionate bond with 1200 other singers, most of them men.” Another woman wrote, “while the membership and leadership are overwhelmingly male, most seem supportive or even enthusiastic about recruiting women’s choruses . . . Anything is possible.”

Besides the documentation that allows a researcher to construct the changing gender dynamics and composition of this musical world, the papers also are suggestive of the way that a group like Artemis helped build a sense of community and shared identity. Artemis Singers performed several times a year in Chicago. Sometimes the events were consciously political, as when they did a benefit concert to raise money for Gay Community News, a Boston-based LGBT weekly with very progressive politics. Sometimes the events were benefits to support Artemis, none of whose members were paid, but for whom the expense of traveling to festivals and purchasing music could be costly.

I’m not sure how one measures the impact of a group like Artemis. But, coming across comments like the concert was “a smashing success” or an event was filled with “magical moments” certainly suggests a collective power to the experience. It was not uncommon for 200- 300 people to attend these musical events in various community venues. One measure of the appeal of Artemis, perhaps, is the fact that in 2017, thirty-seven years after its founding, the Artemis Singers are still performing!

Comments