In the Archives | The 1987 March on Washington Committee: The Chicago Chapter

BY John D'Emilio ON December 21, 2016

While the archival collections at Gerber/Hart are grounded in the history of Chicago, inevitably some of the papers reach beyond the city to illuminate national events. They reveal connections between the local and the national and the impact of each on the other. The papers of the Chicago chapter of the 1987 March on Washington Committee are a case in point.

While the archival collections at Gerber/Hart are grounded in the history of Chicago, inevitably some of the papers reach beyond the city to illuminate national events. They reveal connections between the local and the national and the impact of each on the other. The papers of the Chicago chapter of the 1987 March on Washington Committee are a case in point.

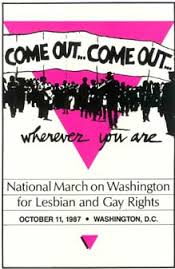

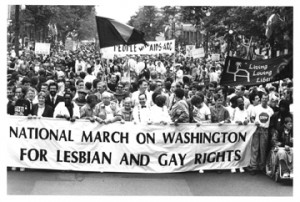

The importance of the 1987 March on Washington cannot be overstated. It put the organized LGBT community on the national stage as never before. There had been a first lesbian and gay national march in 1979, but it drew fewer than 100,000 people to Washington. By the standards of the time, that marked it as decidedly unimpressive. By 1987, just eight years later, much had changed. The AIDS epidemic was raging across America, killing men who had sex with men in staggering numbers. The Reagan administration was disgracefully ignoring it. In 1986, in Bowers v. Hardwick, the Supreme Court added to the fury by upholding the constitutionality of state sodomy laws, with language that was gratuitously contemptuous of same-sex love and relationships. Put all this together, and the result was a march of 500,000 people in October 1987, perhaps the largest protest march to ever assemble in the nation’s capital.

But there was more. There was also mass civil disobedience and arrests in front of the Supreme Court, a mass wedding of same-sex couples to protest the absence of family recognition, and the powerful display, for the first time, of the Names Project Memorial Quilt on the Washington Mall. Key speakers at the rally were the Reverend Jesse Jackson, long-time African-American civil rights leader and a candidate in 1984 for the Democratic presidential nomination; Cesar Chavez, head of the United Farmworkers Union and perhaps the most visible Chicano leader in the U.S.; and Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization for Women, the largest feminist organization in the United States. Their participation was a dramatic sign that the LGBT movement had come of age and was recognized as a component of the broad struggle for social and economic justice in the United States.

Materials in the papers of the Chicago’s MOW Chapter provide a glimpse into just how wide and deep the organizing for the March was. The national steering committee had representatives from 18 states, and there were local committees in 43 states. For instance, three cities in Alabama, six in Georgia, and three in Maine had an organizing structure to get people to Washington. The Chicago chapter papers contain a list of endorsers of the March that filled several pages. It included labor unions, religious groups, and women’s organizations, as well as national, state, and local elected officials. It is worth remembering that every one of those endorsements came because an LGBT activist reached out to key figures in those groups, talked about the March and the issues, and persuaded them to lobby within their organization for an endorsement.

The papers also contain extensive materials about civil disobedience and the kind of training that was provided to individuals. A condition of joining in the civil disobedience outside the Supreme Court was that participants belong to a local affinity group. This meant that, in the summer and early fall of 1987, deep and trusting relationships were forming among groups of activists in cities across the country. As I looked through this material I could not help but wonder how much this contributed to the explosion of local direct action protests by ACT UP and other AIDS-activist groups in the months after the March on Washington, both in Chicago and around the country.

Besides the window that this collection opens into the scope and reach of national preparation, it also naturally gives a close sense of what the organizing looked like and accomplished in Chicago. Julie Valloni and Victor Salvo were the co-chairs of the Committee. In the course of organizing Chicagoans to go to Washington, they and other committee members sought local endorsements, a process that undoubtedly built support for a city non-discrimination ordinance which still hadn’t passed in 1986-87. They also worked closely with media in Chicago; one result was front-page coverage of the March by the Chicago Sun-Times. Perhaps the most visible local achievement was the endorsement letter the Committee received from Mayor Harold Washington. “It is with enthusiasm that I endorse the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights,” he wrote in his letter of September 17. “The breadth of the issues highlighted by the March – against racism and apartheid, as well as for civil rights – is consistent with the historic thrust of struggles for civil rights in this country.” Working hard to get a civil rights ordinance passed in Chicago, Mayor Washington also wrote: “The March will in turn support passage of a comprehensive Human Rights Ordinance here in Chicago.” Such a law was finally enacted a year after the March on Washington.

Besides the window that this collection opens into the scope and reach of national preparation, it also naturally gives a close sense of what the organizing looked like and accomplished in Chicago. Julie Valloni and Victor Salvo were the co-chairs of the Committee. In the course of organizing Chicagoans to go to Washington, they and other committee members sought local endorsements, a process that undoubtedly built support for a city non-discrimination ordinance which still hadn’t passed in 1986-87. They also worked closely with media in Chicago; one result was front-page coverage of the March by the Chicago Sun-Times. Perhaps the most visible local achievement was the endorsement letter the Committee received from Mayor Harold Washington. “It is with enthusiasm that I endorse the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights,” he wrote in his letter of September 17. “The breadth of the issues highlighted by the March – against racism and apartheid, as well as for civil rights – is consistent with the historic thrust of struggles for civil rights in this country.” Working hard to get a civil rights ordinance passed in Chicago, Mayor Washington also wrote: “The March will in turn support passage of a comprehensive Human Rights Ordinance here in Chicago.” Such a law was finally enacted a year after the March on Washington.

The last thing I’ll mention about this collection is a laugh that it elicited. In October 1986, the Vatican issued a major document on homosexuality that provoked a great deal of criticism and outrage, since it supported a theology that defined homosexual behavior as criminal. But one result was that, in Chicago, it led to the formation of a new group called “P.O.P.E.” The letters stood for “Pissed-Off Pansies Energized.” You’ve got to love our sense of humor!

Comments