In the Archives | The Irwin Keller Papers: 1987 Sexual Orientation and the Law Conference

BY John D'Emilio ON January 9, 2017

To research and write about Chicago’s LGBT history is to engage in a form of what’s often described as “local” history, writing about a particular place within a larger nation. Yet local history also reaches beyond the place it describes. The “local” can be used to illustrate broader historical patterns and to make generalizations about an era or a topic. And, sometimes, a place like Chicago can be the setting for events that might be considered national in their reach and consequence.

To research and write about Chicago’s LGBT history is to engage in a form of what’s often described as “local” history, writing about a particular place within a larger nation. Yet local history also reaches beyond the place it describes. The “local” can be used to illustrate broader historical patterns and to make generalizations about an era or a topic. And, sometimes, a place like Chicago can be the setting for events that might be considered national in their reach and consequence.

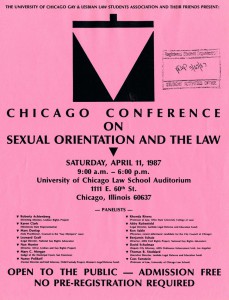

Such was the case in April 1987 when Chicago hosted a conference on “Sexual Orientation and the Law.” Held at the University of Chicago, it was organized by the Gay and Lesbian Law Students Association at the University. Twenty years later, Irwin Keller, who was one of the key organizers of the Conference and a student in the Law School, donated the papers related to the conference to the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives. The Keller Papers provide great insight into the state of the law in the mid-1980s and the strategic thinking of key LGBT legal activists.

Think about the moment. It was several years into the AIDS epidemic, with caseloads and deaths growing in number exponentially. The Reagan presidency was unrelentingly hostile to anything gay, completely ignored the AIDS crisis, and welcomed the religious right into the center of the Republican Party. And, as all this was going on, in June 1986 a 5-to-4 Supreme Court decision in the Bowers v. Hardwick case upheld the constitutionality of state sodomy laws. Bad as the decision waBowers v. Hardwick cases, the language used by the justices in the majority was hostile and derogatory. It described the claims made by those challenging the constitutionality of sodomy statutes as “facetious.” The laws, it said, were rooted in “millennia of moral teaching.” The Constitution offered “no such thing as a fundamental right to commit homosexual sodomy.”

But sometimes defeats can have benefits. Hardwick was a spur to action. It helped to create the demand for a national March on Washington, scheduled for October 1987, a march that would prove to be a demonstration of staggeringly large numbers. And it provided the impetus for members of the Gay and Lesbian Law Students Association at the University of Chicago to propose and organize the first national conference on “Sexual Orientation and the Law,” scheduled for April 11, 1987.

Organizers of the conference cast a wide net. They sent mailings announcing the conference to every law school in the country, hoping not only to reach law students everywhere but also, perhaps, to spur LGBT law students to organize. Estimates of the number who attended the conference that day ranged from five to six hundred. The conference planners also sent invitations to participate to a broad range of legal activists and constitutional lawyers.

The list of those who spoke at the conference reads like a roll call of the pioneers in LGBT legal activism: Thomas Stoddard, Executive Director of Lambda Legal Defense, the first national LGBT legal organization, and Abby Rubenfeld, who was Lambda’s legal director; Nan Hunter, the founding director of the ACLU’s Lesbian and Gay Rights Project; Mary Dunlap, a lawyer who just a few weeks before had argued the “Gay Olympics” case before the Supreme Court and was awaiting the Court’s decision in the case; Roberta Achtenberg, the chief attorney for the National Lesbian Rights Project; and Nancy Polikoff, who had been an attorney for the Women’s Legal Defense Fund and helped cut a path for feminist and LGBT family law.

At times the tone of the sessions was somber. On the opening panel, Tom Stoddard commented on the impact of Hardwick. Looking back on some earlier lower court victories, he said that Hardwick “erases that progress in the federal courts to a very strong degree . . . [and] makes it harder to win on state issues as well.” Evaluating the state of immigration law as it related to lesbians and gays, another panelist frankly said “it is a mess.” Panelists debated whether it made more sense in the future to argue cases on the basis of equal protection principles or from the perspective of the right to privacy. A theme that surfaced repeatedly was the impact that the AIDS epidemic was having. It was stoking deeply irrational fear and prejudice, encouraging more overt discrimination, and justifying that discrimination because of the threat to public health.

Yet there was also a fighting tone to many of the presentations and discussions. Despite the loss in Hardwick, speakers agreed that it was “a risk we had to take.” The loss in the Supreme Court would encourage activists to work for state repeal and lawyers to explore whether some state constitutions might provide grounds for court challenges. Discussions of family law seemed to produce a great deal of energy. In 1987, no state sanctioned same-sex intimate relationships, and state cases about child custody for lesbian mothers were mixed in their outcome. Anticipating the intensifying focus that the 1990s and beyond would bring to marriage and other forms of family law, Abby Rubenfeld stated unambiguously that “we need the sanction of the state” and Nan Hunter declared “we should have it all.” Hunter explained her support of a fight for access to marriage in terms of “the power of marriage as a symbol.”

Most of all, perhaps, the conference was valuable because of the power of bringing so many legal activists together to discuss what the future might bring. As Keller described it in a letter he wrote when he donated the papers to Gerber/Hart, “it was a hugely exciting event – the air was alive with crisis and possibility.”

Comments