Queering the Indy 500

BY Eric Gonzaba ON May 24, 2015

That’s right. I’m attempting the impossible. I’m going to suggest that there is something queer about the Indy 500. Any event that brings in a viewership of nearly six million people is bound to be a little gay, right?

That’s right. I’m attempting the impossible. I’m going to suggest that there is something queer about the Indy 500. Any event that brings in a viewership of nearly six million people is bound to be a little gay, right?

If you’re not familiar, the Indianapolis 500 is a car race that takes place every May in Speedway, Indiana, just outside the state capital of Indianapolis. The speedway itself is arguably the largest arena in the world, with a seating capacity of more than 400,000. To give you some perspective, that’s five times the seating capacity of the Dallas Cowboys’ stadium. Point being: the 500 is a big deal, not just for Hoosiers, but to lots of racing fans.

But is there really anything gay about the Indy 500? After all, the race has no halftime show like during the Superbowl to relieve gay men from the boredom of football with the likes of Beyonce or Katy Perry, even if just for a painfully short ten minute set. Ok, I’m being extremely stereotypical, but people buy into these stereotypes, that all queer people live by a set standard of likes and dislikes, that we all bow to the gods of urbanism, pop, and liberalism.

As important as it is to find and identify the unique sites of our LGBT communities (the underground urban discos, the disappearing feminist bookstores, the black fraternities, the vogue balls etc.), it’s quite extraordinary to discover the ways queer communities in the past sought to both integrate and remake mainstream cultural events and sites like the Indy 500.

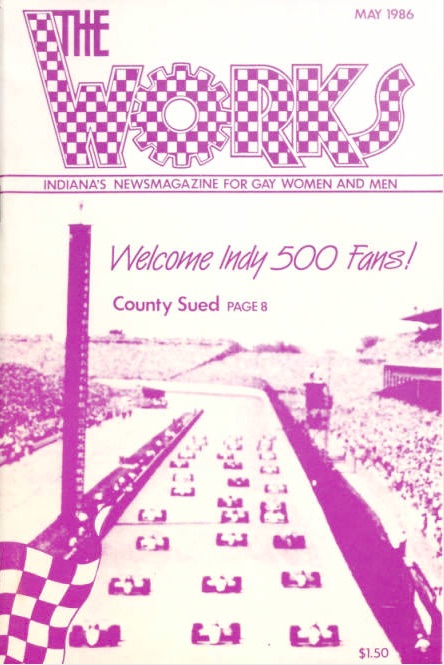

Looking through Indianapolis gay magazines of the past 30 years, it’s incredible to see the warm welcome of gay fans to the racing capital. The entire cover of the May 1986 issue of Indiana’s gay newsmagazine The Works was a greeting message to out of town gay racing fans. As one queer commentator put it, “Hope to see all you fags up in Indy this month to ‘see’ the 500 race,” probably in reference to either the quickness of the Indy racecars or perhaps the draw of gay men to other, non race events in May. Either way, the race meant at least something to Indy’s gay community.

Throughout the 1980s, Indianapolis’ queer community used the race and its out of town gay fans as a reason to congregate and party. Indianapolis’ gay bars hosted race-themed disco dances, complete with drag queen contests like the “Club 500 Queen” or the “Speedway Housewives” as well as the “500 Follies.” Disco divas like Linda Clifford were brought in to entertain fans over the qualification weekends and the famous race day.

Hardcore race fans could watch the races and local bars and clubs during special barbecue cookouts. A 1984 gay writer suggested that though latecomer gay race fans probably couldn’t get grandstand seats on the last weekend before race day, infield tickets were still on sale. “If you thought the Romans had orgies,” the columnists wrote, “try the infield!”

Even the race’s longtime traditions have a queer angle. For over forty years, Jim Nabors of Gomer Pyle fame sang “Back Home Again in Indiana” just before the race to the delight of adoring race fans. In 2013, Nabors married his longtime partner of nearly forty years, Stan Cadwallader. Granted, Nabors’ sexuality remains largely unknown to many Speedway fans but this didn’t stop the infamous Westboro Baptist Church from protesting the event in 2014 (Nabors’ last singing appearance), with the hate group citing Nabors’ homosexuality as one of their main grievances. Regardless of the Westboro morons, I cannot help to think how ironic it is that a state marred in scandal the past few months over allegations of anti-gay discrimination and religious freedom could let a gay man become so attached to a time honored Hoosier tradition.

Today’s racing fans don’t have to look very far to find likeminded compadres. In recent years, a dedicated queer racing community has sprung up online. Sites like Queers4Gears serve as resources for dedicated gay Indy and NASCAR racing fans, offering visitors “gaynalyses” as opposed to traditional, yawn-inducing coverage on conventional news platforms. Queers4Gears founder Michael Myers presents balanced reporting on races, but his queer perspective means a new vocabulary fit for his gay audience, sometimes, for example, referring to drivers as “divas.”

Maybe it’s not important whether or not there is a queer history of the Indy 500. Maybe we should just leave the pit stop and investigate how LGBT people are not always separatists but sometimes active definers of wider, normative culture. The 500 is one reminder that our unique queer perspectives can penetrate even the most “redneck” of institutions.

Comments