Looking back and Listening: Memories of Stonewall

BY Chris Gioia ON June 27, 2017

“Sheridan Square this weekend looked like something from a William Burroughs novel as the sudden specter of ‘gay power’ erected its brazen head and spat out a fairy tale the likes of which the area has never seen.” [1] This is how Lucian Truscott IV rather disparagingly characterized the Stonewall rebellion of 1969 in his eyewitness account published in the Village Voice on July 2nd of that year. The event was indeed something never before seen in New York City’s West Village, but was not the first time LGBT people stood up to police harassment. The Black Cat Tavern raid in Los Angeles and the Compton’s Cafeteria riots in San Francisco a few years prior also saw members of the community fight back against unfair treatment, police brutality and discriminatory laws that targeted the most unambiguous members of the community.

Its hard to imagine that in New York City in 1969, laws prohibited members of the same sex dancing together, restricted the sale of alcohol to homosexuals and penalized those who wore articles of clothing of the opposite sex, but it would take years of activism and action to have these officially taken off the books in the following decades. So, how did the Stonewall Inn become the birthplace of LGBT civil rights? Many details are hard to nail down and many debates have focused on the myths and mysteries of the Stonewall incident, but specific memories and stories help to paint a picture of the place and of the times. Bars like the Stonewall Inn represented a kind of reluctant haven for New York City’s downtown gay scene. Most patrons had a love hate relationship with the bar and its mafia controlled operators. The drinks were weak and over priced, the ambiance was dive bar but the vibe was by most accounts intoxicating if not fully liberating.

Bruce Monroe, who was a college student visiting from Indiana in 1969, describes his memory of Stonewall to me:

I remember … two dance floors and a big long wall down the middle. But I remember it being a very young lively crowd that I could relate to. It was like really exciting to see all these other young men that were around my age. I guess it was one of the most popular places for dancing in NY at that- there weren’t very many places around like that. And I remember having a great time there and I remember having to leave by myself because my friends had found elsewhere to spend the evening.

Historian John D’Emilio’s experience of the West Village as a college student in the late 1960’s is of a “whole gay world.” On two occasions he visited the Stonewall Inn with a friend and remembers the following:

. . . so anyway we go to Stonewall and of course the thing that was immediately apparent to me I mean besides the fact that it was, unlike Julius’ where there were a lot of people but it was conversation, and it was kind of quiet, Stonewall was wildly noisy and what do they have, but go go boys who were dancing you know, up on a platform wearing you know, kinda nothing, like a g-string, or just underpants, and it seemed very exciting to see and experience something like that!

Author Felice Picano has written about Stonewall and been involved in gay literature/publishing since the 1970’s. He wasn’t a fan of Stonewall in 1969, but recalls that it could be useful:

. . . if you found somebody interesting and you sorta wanted to feel them up and feel them out before you took them home you’d take them around the corner to the Stonewall and slow dance in the dark and figure out what you wanted . . . it became by the time the incident happened, a place for trannies and for people who were not quite street people but almost, and sometimes the hustler boys who would hang out in front of it in the park in Sheridan Square would go in too. So it had this very, very mixed vibe and, and I was always hearing that it was closing down, that it was going bankrupt.

Trans activist Miss Majors introduces her story to Felice Picano in a rare correspondence:

Miss Majors: I’d had a tough day, and I heard that that singer Judy Garland had died. I wasn’t a fan of hers, but I didn’t feel like being alone, so I went down to the Stonewall. That was our club, where the other “T’s” and I could hang out and relax and be ourselves. [2]

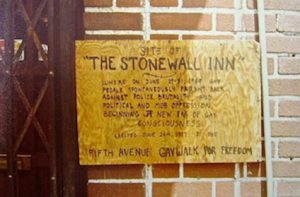

Stonewall Plaque placed in 1977 by the 5th Ave. Gay Walk of Freedom. LGBT Community Center Archives, Grillo Collection.

Pioneering gay journalist Mark Segal provides a first hand account of being inside the bar that night:

I remember the lights flashing. I remember asking somebody …“what does that mean?” And someone said, “Oh we’re just going to be raided!” And everybody who was a regular there took that very nonchalant. They were just used to it cause that was part of what life was like for gay people at that point. Me on the other hand had never been through a raid. I tried to look nonchalant but I gotta tell you its not –[laughs] I was very nervous. … As people were coming out they started forming a semi circle around the door and that eventually – and as the police let out more and more people at one point the only people left in the bar or most of the people left in the bar were the people that worked there and the police. At which point people just started throwing things at the door. Um, [sigh] that’s basically when people started breaking things, running up and down the street. [3]

Activist Martha Shelly recalls in my interview with her last year, how the liberation movement was energized by Stonewall:

Monday I read about the riots in the newspaper and I thought that was what it was about! I read about the Stonewall Riot in some small article in the New York Times or the New York Post I don’t remember which and I immediately called . . . Jean Powers and she was the person who was getting out the newsletter and organizing meetings. I called her and said we have to have a protest march. She told me to call the head of the Mattachine Society and she said if they’re interested we could jointly sponsor it. …So I called Dick Leitsch who was the head of the Mattachine Society. He said they were having a meeting at Town Hall to discuss all of these things and what it meant for the gay community and come to the meeting and put my proposal out and that’s what I did.

Craig Rodwell, owner of the Oscar Wilde Memorial bookshop on Mercer St. at the time of the riot, sums up the significance of Stonewall:

Immediately I saw that this was something that was going to have an impact in the future for the movement because I’d been saying for years that something would happen- there would be a spark. I recognized instantly that this was it.[4]

Today the Stonewall Inn is an iconic symbol of the birth of LGBT rights and has secured its place in history by being designated a National Monument. To learn more about the liberation movement and hear more of the interviews I conducted visit www.stonewallhistory.us and for additional first hand testimony about Stonewall listen to a wonderful radio segment from 1989 here: Remembering Stonewall

At a performance upstairs at the Stonewall Inn not too long ago, I was shoulder to shoulder with a truly diverse mix of patrons: trans women and men, lesbians, drag queens, regulars who call the bar a hangout, more than a few allies, and of course tourists checking another landmark off their list. I like to think that the pioneers of the liberation movement who have passed, would be proud of what the reincarnated Stonewall represents, but I’m sure if asked a contentious debate would ensue. After all, if its not worth arguing about, was it worth fighting for?

Gay Power!

[1] Lucian Truscott IV, “Gay Power Comes to Sheridan Square,” Village Voice, July 2, 1969, accessed December 10, 2016, http://www.villagevoice.com/news/stonewall-gay-power-comes-to-sheridan-square-6670443.

[2] Felice Picano, “The Remains of the Night: Six Observers: Felice Picano Talks with Eyewitnesses to the Stonewall Riots,” The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, 2015 (4): 29.

[3] Mark Segal, interview by Christopher L. Gioia, February 7, 2017, interview.

[4] Tina Crosby, “The Stonewall Riot Remembered, Excerpt 2,” Stonewall: Riot, Rebellion, Activism and Identity, accessed April 14, 2017, https://stonewallhistory.omeka.net/items/show/25.

In the Archives | Go Out and Interview Someone! The Robinn Dupree Papers

BY John D'Emilio ON November 30, 2016

Our life stories are the core content of LGBT history. Yes, our organizations and businesses produce records that detail important work. And mainstream institutions and social structures affect us deeply. But the texture and the challenges of what it means to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender at different times and in different places will only fully emerge if we make an effort to collect a broad range of our life stories. Reading – or hearing – the life story of an individual is not only compelling and absorbing in its own right. It can also open doors of understanding and offer revealing insights into what it was like to be . . . well, whatever combination of identities the individual brings to the interview. Each of our life stories will have something to tell us beyond the L,G,B, or T. We are also the products of regional culture, of racial and ethnic identity, of religious upbringing, of our particular family life, of class background, of work environments, and other matters as well.

The truth of this was brought home to me when I stumbled upon the small box of papers at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives labeled “Robinn Dupree.” In November 1996, a professor in folk studies at Western Kentucky University took his class of graduate students to Nashville to see a performance of female impersonators at a bar, The Connection. One of those students, Erin Roth, was so impressed by the event and by the lead performer, Robinn Dupree, that she asked for permission not to do her seminar paper on the assigned project – interviews/studies of “riverboat captains and old-time musicians” – but instead be allowed to interview Dupree and write about the art of female impersonation. The professor said yes, and so Roth conducted two interviews with Dupree, in March and April 1997. Fortunately for everyone else, she donated the tapes, a typed transcript, and her seminar paper to Gerber/Hart, so that Dupree’s account of her life is now available for study and inclusion in our collective history.

To summarize her story briefly: Dupree was born in 1952 in Chicago, her mother of Sicilian background and her father a Puerto Rican of African heritage. When she was in the 8th grade, she told her mother she was gay. As a teenager, she discovered the Baton Show Lounge, run by Jim Flint and already well-known for its performances by female impersonators. Soon she was sneaking out of the house to go there regularly. “It’s like I found what I wanted to do,” she told Roth, and soon Flint was coaching her and she began performing regularly.

Dupree performed at the Baton for almost a decade, and then moved on to another club, La Cage. In 1982, her boyfriend of ten years, who had connections to the Mafia, was killed in a car bombing outside their apartment building. Dupree realized it would be best to leave Chicago quickly, and she resettled in Louisville, Kentucky, where she rapidly made her way into the local female impersonator scene. Over the next decades, she performed for long stretches in Louisville, Nashville, and Indianapolis. According to online sources, her last show before retiring as a performer was just a few months ago, on February 13, 2016.

Reading the transcript of the interviews as well as Roth’s paper, I was struck by certain themes, some of which likely have broad applicability and some of which might be particular to Dupree. One involves economics. For those like Dupree who take the work of impersonation seriously as an art form and devote themselves to it, the economic realities can be harsh. On one hand, costs are high: the dresses, the jewelry, and everything else associated with the glamor of their performance are expensive, and new apparel has to be bought regularly for new shows. On the other hand, wages are low. Performers depend on tips, but these are unpredictable and often will not support them sufficiently. Thus, most impersonators need to have a day job, but that brings them up against the gender boundaries of the culture.

Another theme is family. As Dupree became a well-known, successful, and seasoned performer, younger impersonators-to-be came to her for advice, tutoring, and support, just as she had received from Jim Flint when she was starting and barely out of her teens. To many, she was their “mother,” and to Dupree, they were her “daughters.” The terms conjure up images of a warm and intimate family of choice, which it is. But behind the pull to use those terms is a harsh reality. After Dupree started performing, her biological mother broke off contact with her, and they remained separated for ten years. “Most people who do drag or want to become women, their family totally disowns them,” Dupree told Roth in their interview. Although Dupree acknowledged that much had changed in the 25-plus years since she had started performing, the loss of connection to families of origin remains true for many. Thus the relationships that were established had significant emotional and practical meaning. Dupree’s daughters often lived with her for long stretches as they worked to establish a life for themselves. Yes, it was a chosen family, but it was also a deeply needed family.

A third issue emerged in reading the interview with Dupree: the complexities and shadings of identity. At the time of the interview, in 1997, transgender had just recently established itself as a term of preference in the LGBT movement and in activist circles. Dupree described herself as “a pre-operative transsexual . . . I live every day of my life as a woman.” She had had surgeries done on her face to accentuate a kind of feminine beauty. She had also done hormone treatments in order to increase her believability as a performer in the world of female impersonation. “That’s why I actually ended up taking hormones and becoming a pre-op,” she told Roth. “Not to become a woman, but to look as much like a woman on stage as possible.” And within this world of stage performance, at least in the decades in which Dupree was an important presence, a range of self-understandings existed. “I have some daughters who want to be just entertainers. Then I have other daughters who want to go all the way through and become a woman.”

The Dupree oral history at Gerber/Hart is a treasure. We need more of them. Go out and interview someone – now!

In the Archives | GLAAD Chicago

BY John D'Emilio ON November 16, 2016

On more than a few occasions in the last three or four years, as I’ve read the New York Times or the Chicago Tribune in the morning, I have had the sensation that I was reading an LGBT community newspaper. The range and number of stories have sometimes been staggering. There have been stories on the fight for marriage equality, of course, but I was also encountering news about changes in federal policies, tech industry initiatives, sports figures coming out, arts and culture profiles, young people organizing in their schools, op-ed pieces, and much, much more. In addition to the quantity of material, the positive perspective embedded in the reporting has also been noteworthy. The underlying point of view in the coverage and reporting has been one that affirms and validates LGBT communities and our fight for acceptance and justice.

Needless to say, it was not always so. In the pre-Stonewall years, before the rise of a militant movement, more typical coverage about our community was the alternation between a deep silence – no mention or recognition at all – and lurid stories that emphasized crime, danger, and moral corruption. This didn’t all magically change after Stonewall and the rise of a gay liberation movement. Part of what contributed to the rapid spread of AIDS in the 1980s was the tendency of the media either to ignore the story, thus perpetuating ignorance and an inability to act effectively against its spread, or to sensationalize the epidemic and thus perpetuate the deep cultural and institutional bias against men who have sex with men.

I received a powerful reminder of how slow the media was to change when I explored the GLAAD-Chicago collection at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives. The seven boxes of material, which span the first half of the 1990s, were donated by Randy Snyder, who served as the chapter’s executive director. GLAAD, which stands for Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, was a media watchdog organization formed in New York City in 1985 by Vito Russo and Darrell Yates Rist, both writers, as well as others. They acted in response to some of the horrifying coverage of AIDS coming from papers like the New York Post, owned by Rupert Murdoch. By the early 1990s, GLAAD had spawned perhaps a dozen local chapters, of which Chicago was one.

One of the major emphases in the work of GLAAD was its monitoring of the newly powerful “Religious Right.” For those interested in learning about and exploring the Religious Right more deeply in these years, the collection is a rich source of material. GLAAD kept track of and collected publications produced by organizations like the Traditional Values Coalition, the Family Research Institute, Focus on the Family and, locally, the Illinois Family Institute that, even today in 2016, is out there rousing opposition to initiatives to protect the safety and well being of transgender youth. The work of Paul Cameron especially drew GLAAD’s attention. A psychologist who was expelled from the American Psychological Association in 1983, Cameron produced reports with titles like “Criminality, Social Disruption, and Homosexuality”; “Child Molestation and Homosexuality”; and “Murder, Violence, and Homosexuality.” The GLAAD-Chicago papers also provide insight into the organizing being done to contain and discredit the Religious Right. Materials produced in the 1990s by organizations like the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and People for the American Way can be found here.

Interestingly, the work of a media watchdog group like GLAAD in these years was not confined to exposing extremists. Mainstream media outlets, including those that might be defined as liberal, needed to be targeted as well. A case in point was the Chicago Sun-Times, the city’s liberal daily paper. In the space of two months in 1994, the paper published two editorials that, shockingly, sounded as if the editorial board had lifted passages out of a Religious Right report. In response to the suburb of Oak Park extending medical benefits to the same-sex partners of town employees, the Sun-Times editorialized about “the importance of more traditional families” and “the central role in society traditional families must still assume.” Then, in an editorial coinciding with the 25th anniversary celebrations of the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969, the Sun-Times declared: “we oppose extending favored status to gays . . . the heterosexual majority is justifiably concerned that its values not be marginalized . . . and that a new set of rights not be extended to a privileged class.” GLAAD’s response was uncensored: “you have bought into the Religious Right’s lies and myths,” it wrote to the editorial page editor. Your claims, it said, were “vague and fallacious.”

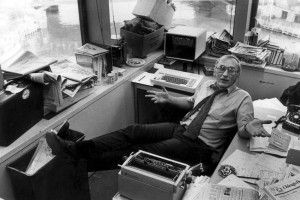

As with so many collections, there are also the jaw-dropping surprises. The GLAAD-Chicago papers include a “Mike Royko” folder. The Pulitzer Prize winning columnist was a fixture of Chicago journalism for decades. He had a take-no-prisoners style of writing that called out politicians and other public figures. His biography of Mayor Daley, Boss, was a best seller. In the folder is an unsigned typed memo, dated May 22, 1995, and with it a copy of a police report, dated December 17, 1994, documenting Royko’s arrest on DUI and resisting arrest charges in conjunction with a car crash. The memo called attention to comments of Royko’s documented in the report. Among other things, he screamed at the responding officer “you cocksucker” and “get your hands off me, you fucking fag.” Later he yelled, “Get away from me. What are you, fags?” and “Jag off, queer,” and finally, “What’s your ethnicity, you fag?” Because of Royko’s stature, the memo and report, which was sent to several LGBT organizations, created a media moment in Chicago

All this and more are to be found in the collection. GLAAD’s work helps explain why the tone and content of media coverage of LGBT issues is different today than it was even two decades ago. It didn’t happen by magic, by some mysterious process of evolution that brings progress. It took activist commitment and energy, and some of that commitment and energy are documented in the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.

In the Archives | The Melissa Ann Merry Papers

BY John D'Emilio ON October 31, 2016

One of the pleasant surprises that comes from snooping through the collections at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives is seeing how rich with information even small collections can be. The papers of Melissa Ann Merry are a perfect illustration of that.

One of the pleasant surprises that comes from snooping through the collections at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives is seeing how rich with information even small collections can be. The papers of Melissa Ann Merry are a perfect illustration of that.

Merry was a Chicago-based bisexual activist and performer. Born in Canton, Ohio, in 1963, she went to college at Eastern Michigan University and then moved to Chicago soon after graduating in 1986. It was in Chicago that she came out as bisexual, and she soon plunged into a world of bisexual activism that was coming together in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Locally, she got involved in the Bisexual Political Action Coalition (BIPAC) and was also a Midwest representative to the national organization BiNet (Bisexual Network of the USA), which grew out of the first national bisexual conference, held in San Francisco in June 1990. The papers she donated to Gerber/Hart consist of three boxes of material, almost all from between 1990 and 1995.

The first thing that emerged very clearly from surveying Merry’s papers is how important both the 1993 March on Washington and the 1994 Stonewall ’25 commemoration in NYC proved to be for bisexual activism and mobilization. Merry has several folders of material on each of them. First there was the organizing that needed to happen in order to have “Bi” be included in the official name of the 1993 March. Once that was achieved, planning for the March provided a great spur to local organizing across the U.S. to make sure that bisexuals participated in and were targeted by the efforts to guarantee a vast turnout in Washington in April 1993. Thus, the March proved to be not a single event, but a tool that had consequences afterward in the heightened level of local organization that it produced. The same can be said of the buildup for and aftermath of Stonewall ’25, which brought massive numbers of people to New York and achieved extraordinary media visibility. Not only did more local organizing emerge from both of them, but they also led to higher levels of national networking.

The increasing breadth and depth of bisexual organizing also emerges from another feature of Melissa Ann Merry’s papers. The collection contains a substantial number of bisexual publications from the early to mid-1990s. Among them are Anything That Moves, from the San Francisco Bay Area; Bi-Lines, from Madison, Wisconsin; Bi-Monthly from Champaign-Urbana, Illinois; the Boston Bisexual Women’s Network Newsletter; North Bi Northwest, out of Seattle; Bi-Atlanta; Bi-Centrist, from Washington, DC; Bi-Lines, from Chicago; and Bi-Focus from Philadelphia.

The increasing breadth and depth of bisexual organizing also emerges from another feature of Melissa Ann Merry’s papers. The collection contains a substantial number of bisexual publications from the early to mid-1990s. Among them are Anything That Moves, from the San Francisco Bay Area; Bi-Lines, from Madison, Wisconsin; Bi-Monthly from Champaign-Urbana, Illinois; the Boston Bisexual Women’s Network Newsletter; North Bi Northwest, out of Seattle; Bi-Atlanta; Bi-Centrist, from Washington, DC; Bi-Lines, from Chicago; and Bi-Focus from Philadelphia.

These newsletters and community magazines suggest that bisexuals were organizing on a far more extensive scale than is commonly recognized. In rare instances, an individual might prove capable of writing, producing, and distributing such a publication. But, typically, it requires a group to do the work of gathering the information, writing it up, and building an audience to read the material and sustain the newsletter or magazine. The existence of publications like these also suggests that there were sufficient groups and issues and campaigns to write about, thereby confirming that this was a period of intense and productive bisexual activism.

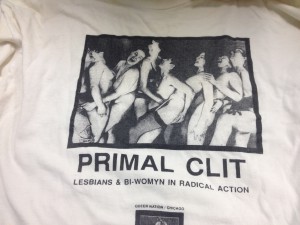

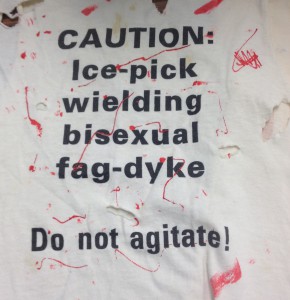

Finally, working my way through these three boxes of Merry’s papers also brought many smiles to my face. Besides documents, her collection also includes physical objects – tee-shirts, buttons, and political stickers. Many of them display a sense of humor that will easily produce chortles of laughter for the knowing but may also perhaps produce a moment of shock that successfully grabs the attention of those who may never have thought of bisexuality before. To mention just a few: there is a tee-shirt that read “Caution: Ice-pick wielding bisexual fag-dyke. Do not agitate!” Another portrays a line of women, some back-to-back and others face-to-face, with looks of ecstasy on their faces and the words “Primal Clit: Lesbians and Bi-Womyn in Radical Action.” There were stickers, meant to be placed on poles and walls and cars, one of which read “Bisexuals Don’t Sit on Fences. We Build Bridges!!!” And, finally, many buttons, among them the following: “I’m Bisexual – You’re Confused”; “Bi-Sexuals Are Equal Opportunity Lovers”; and “Two Roads Diverged in a Yellow Wood . . . and I Took Both.”

Finally, working my way through these three boxes of Merry’s papers also brought many smiles to my face. Besides documents, her collection also includes physical objects – tee-shirts, buttons, and political stickers. Many of them display a sense of humor that will easily produce chortles of laughter for the knowing but may also perhaps produce a moment of shock that successfully grabs the attention of those who may never have thought of bisexuality before. To mention just a few: there is a tee-shirt that read “Caution: Ice-pick wielding bisexual fag-dyke. Do not agitate!” Another portrays a line of women, some back-to-back and others face-to-face, with looks of ecstasy on their faces and the words “Primal Clit: Lesbians and Bi-Womyn in Radical Action.” There were stickers, meant to be placed on poles and walls and cars, one of which read “Bisexuals Don’t Sit on Fences. We Build Bridges!!!” And, finally, many buttons, among them the following: “I’m Bisexual – You’re Confused”; “Bi-Sexuals Are Equal Opportunity Lovers”; and “Two Roads Diverged in a Yellow Wood . . . and I Took Both.”

As I said at the beginning of this post, the Melissa Ann Merry Papers might be seen as a relatively small collection of three boxes, but they are packed with material that, cumulatively, provides rich insight into key years of bisexual activism in the United States.