In the Archives | The 1987 March on Washington Committee: The Chicago Chapter

BY John D'Emilio ON December 21, 2016

While the archival collections at Gerber/Hart are grounded in the history of Chicago, inevitably some of the papers reach beyond the city to illuminate national events. They reveal connections between the local and the national and the impact of each on the other. The papers of the Chicago chapter of the 1987 March on Washington Committee are a case in point.

While the archival collections at Gerber/Hart are grounded in the history of Chicago, inevitably some of the papers reach beyond the city to illuminate national events. They reveal connections between the local and the national and the impact of each on the other. The papers of the Chicago chapter of the 1987 March on Washington Committee are a case in point.

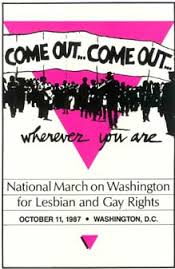

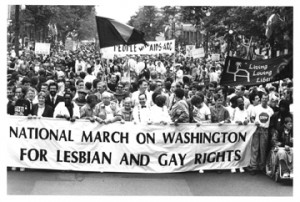

The importance of the 1987 March on Washington cannot be overstated. It put the organized LGBT community on the national stage as never before. There had been a first lesbian and gay national march in 1979, but it drew fewer than 100,000 people to Washington. By the standards of the time, that marked it as decidedly unimpressive. By 1987, just eight years later, much had changed. The AIDS epidemic was raging across America, killing men who had sex with men in staggering numbers. The Reagan administration was disgracefully ignoring it. In 1986, in Bowers v. Hardwick, the Supreme Court added to the fury by upholding the constitutionality of state sodomy laws, with language that was gratuitously contemptuous of same-sex love and relationships. Put all this together, and the result was a march of 500,000 people in October 1987, perhaps the largest protest march to ever assemble in the nation’s capital.

But there was more. There was also mass civil disobedience and arrests in front of the Supreme Court, a mass wedding of same-sex couples to protest the absence of family recognition, and the powerful display, for the first time, of the Names Project Memorial Quilt on the Washington Mall. Key speakers at the rally were the Reverend Jesse Jackson, long-time African-American civil rights leader and a candidate in 1984 for the Democratic presidential nomination; Cesar Chavez, head of the United Farmworkers Union and perhaps the most visible Chicano leader in the U.S.; and Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization for Women, the largest feminist organization in the United States. Their participation was a dramatic sign that the LGBT movement had come of age and was recognized as a component of the broad struggle for social and economic justice in the United States.

Materials in the papers of the Chicago’s MOW Chapter provide a glimpse into just how wide and deep the organizing for the March was. The national steering committee had representatives from 18 states, and there were local committees in 43 states. For instance, three cities in Alabama, six in Georgia, and three in Maine had an organizing structure to get people to Washington. The Chicago chapter papers contain a list of endorsers of the March that filled several pages. It included labor unions, religious groups, and women’s organizations, as well as national, state, and local elected officials. It is worth remembering that every one of those endorsements came because an LGBT activist reached out to key figures in those groups, talked about the March and the issues, and persuaded them to lobby within their organization for an endorsement.

The papers also contain extensive materials about civil disobedience and the kind of training that was provided to individuals. A condition of joining in the civil disobedience outside the Supreme Court was that participants belong to a local affinity group. This meant that, in the summer and early fall of 1987, deep and trusting relationships were forming among groups of activists in cities across the country. As I looked through this material I could not help but wonder how much this contributed to the explosion of local direct action protests by ACT UP and other AIDS-activist groups in the months after the March on Washington, both in Chicago and around the country.

Besides the window that this collection opens into the scope and reach of national preparation, it also naturally gives a close sense of what the organizing looked like and accomplished in Chicago. Julie Valloni and Victor Salvo were the co-chairs of the Committee. In the course of organizing Chicagoans to go to Washington, they and other committee members sought local endorsements, a process that undoubtedly built support for a city non-discrimination ordinance which still hadn’t passed in 1986-87. They also worked closely with media in Chicago; one result was front-page coverage of the March by the Chicago Sun-Times. Perhaps the most visible local achievement was the endorsement letter the Committee received from Mayor Harold Washington. “It is with enthusiasm that I endorse the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights,” he wrote in his letter of September 17. “The breadth of the issues highlighted by the March – against racism and apartheid, as well as for civil rights – is consistent with the historic thrust of struggles for civil rights in this country.” Working hard to get a civil rights ordinance passed in Chicago, Mayor Washington also wrote: “The March will in turn support passage of a comprehensive Human Rights Ordinance here in Chicago.” Such a law was finally enacted a year after the March on Washington.

Besides the window that this collection opens into the scope and reach of national preparation, it also naturally gives a close sense of what the organizing looked like and accomplished in Chicago. Julie Valloni and Victor Salvo were the co-chairs of the Committee. In the course of organizing Chicagoans to go to Washington, they and other committee members sought local endorsements, a process that undoubtedly built support for a city non-discrimination ordinance which still hadn’t passed in 1986-87. They also worked closely with media in Chicago; one result was front-page coverage of the March by the Chicago Sun-Times. Perhaps the most visible local achievement was the endorsement letter the Committee received from Mayor Harold Washington. “It is with enthusiasm that I endorse the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights,” he wrote in his letter of September 17. “The breadth of the issues highlighted by the March – against racism and apartheid, as well as for civil rights – is consistent with the historic thrust of struggles for civil rights in this country.” Working hard to get a civil rights ordinance passed in Chicago, Mayor Washington also wrote: “The March will in turn support passage of a comprehensive Human Rights Ordinance here in Chicago.” Such a law was finally enacted a year after the March on Washington.

The last thing I’ll mention about this collection is a laugh that it elicited. In October 1986, the Vatican issued a major document on homosexuality that provoked a great deal of criticism and outrage, since it supported a theology that defined homosexual behavior as criminal. But one result was that, in Chicago, it led to the formation of a new group called “P.O.P.E.” The letters stood for “Pissed-Off Pansies Energized.” You’ve got to love our sense of humor!

In the Archives | Go Out and Interview Someone! The Robinn Dupree Papers

BY John D'Emilio ON November 30, 2016

Our life stories are the core content of LGBT history. Yes, our organizations and businesses produce records that detail important work. And mainstream institutions and social structures affect us deeply. But the texture and the challenges of what it means to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender at different times and in different places will only fully emerge if we make an effort to collect a broad range of our life stories. Reading – or hearing – the life story of an individual is not only compelling and absorbing in its own right. It can also open doors of understanding and offer revealing insights into what it was like to be . . . well, whatever combination of identities the individual brings to the interview. Each of our life stories will have something to tell us beyond the L,G,B, or T. We are also the products of regional culture, of racial and ethnic identity, of religious upbringing, of our particular family life, of class background, of work environments, and other matters as well.

The truth of this was brought home to me when I stumbled upon the small box of papers at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives labeled “Robinn Dupree.” In November 1996, a professor in folk studies at Western Kentucky University took his class of graduate students to Nashville to see a performance of female impersonators at a bar, The Connection. One of those students, Erin Roth, was so impressed by the event and by the lead performer, Robinn Dupree, that she asked for permission not to do her seminar paper on the assigned project – interviews/studies of “riverboat captains and old-time musicians” – but instead be allowed to interview Dupree and write about the art of female impersonation. The professor said yes, and so Roth conducted two interviews with Dupree, in March and April 1997. Fortunately for everyone else, she donated the tapes, a typed transcript, and her seminar paper to Gerber/Hart, so that Dupree’s account of her life is now available for study and inclusion in our collective history.

To summarize her story briefly: Dupree was born in 1952 in Chicago, her mother of Sicilian background and her father a Puerto Rican of African heritage. When she was in the 8th grade, she told her mother she was gay. As a teenager, she discovered the Baton Show Lounge, run by Jim Flint and already well-known for its performances by female impersonators. Soon she was sneaking out of the house to go there regularly. “It’s like I found what I wanted to do,” she told Roth, and soon Flint was coaching her and she began performing regularly.

Dupree performed at the Baton for almost a decade, and then moved on to another club, La Cage. In 1982, her boyfriend of ten years, who had connections to the Mafia, was killed in a car bombing outside their apartment building. Dupree realized it would be best to leave Chicago quickly, and she resettled in Louisville, Kentucky, where she rapidly made her way into the local female impersonator scene. Over the next decades, she performed for long stretches in Louisville, Nashville, and Indianapolis. According to online sources, her last show before retiring as a performer was just a few months ago, on February 13, 2016.

Reading the transcript of the interviews as well as Roth’s paper, I was struck by certain themes, some of which likely have broad applicability and some of which might be particular to Dupree. One involves economics. For those like Dupree who take the work of impersonation seriously as an art form and devote themselves to it, the economic realities can be harsh. On one hand, costs are high: the dresses, the jewelry, and everything else associated with the glamor of their performance are expensive, and new apparel has to be bought regularly for new shows. On the other hand, wages are low. Performers depend on tips, but these are unpredictable and often will not support them sufficiently. Thus, most impersonators need to have a day job, but that brings them up against the gender boundaries of the culture.

Another theme is family. As Dupree became a well-known, successful, and seasoned performer, younger impersonators-to-be came to her for advice, tutoring, and support, just as she had received from Jim Flint when she was starting and barely out of her teens. To many, she was their “mother,” and to Dupree, they were her “daughters.” The terms conjure up images of a warm and intimate family of choice, which it is. But behind the pull to use those terms is a harsh reality. After Dupree started performing, her biological mother broke off contact with her, and they remained separated for ten years. “Most people who do drag or want to become women, their family totally disowns them,” Dupree told Roth in their interview. Although Dupree acknowledged that much had changed in the 25-plus years since she had started performing, the loss of connection to families of origin remains true for many. Thus the relationships that were established had significant emotional and practical meaning. Dupree’s daughters often lived with her for long stretches as they worked to establish a life for themselves. Yes, it was a chosen family, but it was also a deeply needed family.

A third issue emerged in reading the interview with Dupree: the complexities and shadings of identity. At the time of the interview, in 1997, transgender had just recently established itself as a term of preference in the LGBT movement and in activist circles. Dupree described herself as “a pre-operative transsexual . . . I live every day of my life as a woman.” She had had surgeries done on her face to accentuate a kind of feminine beauty. She had also done hormone treatments in order to increase her believability as a performer in the world of female impersonation. “That’s why I actually ended up taking hormones and becoming a pre-op,” she told Roth. “Not to become a woman, but to look as much like a woman on stage as possible.” And within this world of stage performance, at least in the decades in which Dupree was an important presence, a range of self-understandings existed. “I have some daughters who want to be just entertainers. Then I have other daughters who want to go all the way through and become a woman.”

The Dupree oral history at Gerber/Hart is a treasure. We need more of them. Go out and interview someone – now!

In the Archives | GLAAD Chicago

BY John D'Emilio ON November 16, 2016

On more than a few occasions in the last three or four years, as I’ve read the New York Times or the Chicago Tribune in the morning, I have had the sensation that I was reading an LGBT community newspaper. The range and number of stories have sometimes been staggering. There have been stories on the fight for marriage equality, of course, but I was also encountering news about changes in federal policies, tech industry initiatives, sports figures coming out, arts and culture profiles, young people organizing in their schools, op-ed pieces, and much, much more. In addition to the quantity of material, the positive perspective embedded in the reporting has also been noteworthy. The underlying point of view in the coverage and reporting has been one that affirms and validates LGBT communities and our fight for acceptance and justice.

Needless to say, it was not always so. In the pre-Stonewall years, before the rise of a militant movement, more typical coverage about our community was the alternation between a deep silence – no mention or recognition at all – and lurid stories that emphasized crime, danger, and moral corruption. This didn’t all magically change after Stonewall and the rise of a gay liberation movement. Part of what contributed to the rapid spread of AIDS in the 1980s was the tendency of the media either to ignore the story, thus perpetuating ignorance and an inability to act effectively against its spread, or to sensationalize the epidemic and thus perpetuate the deep cultural and institutional bias against men who have sex with men.

I received a powerful reminder of how slow the media was to change when I explored the GLAAD-Chicago collection at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives. The seven boxes of material, which span the first half of the 1990s, were donated by Randy Snyder, who served as the chapter’s executive director. GLAAD, which stands for Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, was a media watchdog organization formed in New York City in 1985 by Vito Russo and Darrell Yates Rist, both writers, as well as others. They acted in response to some of the horrifying coverage of AIDS coming from papers like the New York Post, owned by Rupert Murdoch. By the early 1990s, GLAAD had spawned perhaps a dozen local chapters, of which Chicago was one.

One of the major emphases in the work of GLAAD was its monitoring of the newly powerful “Religious Right.” For those interested in learning about and exploring the Religious Right more deeply in these years, the collection is a rich source of material. GLAAD kept track of and collected publications produced by organizations like the Traditional Values Coalition, the Family Research Institute, Focus on the Family and, locally, the Illinois Family Institute that, even today in 2016, is out there rousing opposition to initiatives to protect the safety and well being of transgender youth. The work of Paul Cameron especially drew GLAAD’s attention. A psychologist who was expelled from the American Psychological Association in 1983, Cameron produced reports with titles like “Criminality, Social Disruption, and Homosexuality”; “Child Molestation and Homosexuality”; and “Murder, Violence, and Homosexuality.” The GLAAD-Chicago papers also provide insight into the organizing being done to contain and discredit the Religious Right. Materials produced in the 1990s by organizations like the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and People for the American Way can be found here.

Interestingly, the work of a media watchdog group like GLAAD in these years was not confined to exposing extremists. Mainstream media outlets, including those that might be defined as liberal, needed to be targeted as well. A case in point was the Chicago Sun-Times, the city’s liberal daily paper. In the space of two months in 1994, the paper published two editorials that, shockingly, sounded as if the editorial board had lifted passages out of a Religious Right report. In response to the suburb of Oak Park extending medical benefits to the same-sex partners of town employees, the Sun-Times editorialized about “the importance of more traditional families” and “the central role in society traditional families must still assume.” Then, in an editorial coinciding with the 25th anniversary celebrations of the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969, the Sun-Times declared: “we oppose extending favored status to gays . . . the heterosexual majority is justifiably concerned that its values not be marginalized . . . and that a new set of rights not be extended to a privileged class.” GLAAD’s response was uncensored: “you have bought into the Religious Right’s lies and myths,” it wrote to the editorial page editor. Your claims, it said, were “vague and fallacious.”

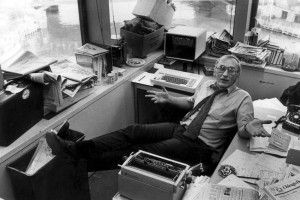

As with so many collections, there are also the jaw-dropping surprises. The GLAAD-Chicago papers include a “Mike Royko” folder. The Pulitzer Prize winning columnist was a fixture of Chicago journalism for decades. He had a take-no-prisoners style of writing that called out politicians and other public figures. His biography of Mayor Daley, Boss, was a best seller. In the folder is an unsigned typed memo, dated May 22, 1995, and with it a copy of a police report, dated December 17, 1994, documenting Royko’s arrest on DUI and resisting arrest charges in conjunction with a car crash. The memo called attention to comments of Royko’s documented in the report. Among other things, he screamed at the responding officer “you cocksucker” and “get your hands off me, you fucking fag.” Later he yelled, “Get away from me. What are you, fags?” and “Jag off, queer,” and finally, “What’s your ethnicity, you fag?” Because of Royko’s stature, the memo and report, which was sent to several LGBT organizations, created a media moment in Chicago

All this and more are to be found in the collection. GLAAD’s work helps explain why the tone and content of media coverage of LGBT issues is different today than it was even two decades ago. It didn’t happen by magic, by some mysterious process of evolution that brings progress. It took activist commitment and energy, and some of that commitment and energy are documented in the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.

In the Archives

BY John D'Emilio ON October 19, 2016

“In the archives.” It’s a phrase that those of us who do history – whether as a profession or a passion or both – have used for a long time. It sometimes serves as shorthand to say that we’re doing research. But it is also often meant literally. “In the archives” is where we have gone to read the letters, diaries, memos, reports, and so many other documents from the past that are the raw material for writing histories of almost anything.

“In the archives.” It’s a phrase that those of us who do history – whether as a profession or a passion or both – have used for a long time. It sometimes serves as shorthand to say that we’re doing research. But it is also often meant literally. “In the archives” is where we have gone to read the letters, diaries, memos, reports, and so many other documents from the past that are the raw material for writing histories of almost anything.

Of course, in the era of the web, much archival material is relocating to hard drives and cloud servers. Many archives are digitizing at least some of their collections, and many individuals and organizations place the written documents they produce on websites as well. The result is that a day spent “in the archives” can now mean a day spent with one’s tablet, at a coffee shop, working one’s way through digitized records of the past.

Still, even with these revolutionary technological changes, the physical reality of archives as places that house the records of the past remains important. And this seems particularly true for the LGBTQ community. The generations of “wearing a mask” and having to pass as heterosexual, of invisibility and enforced silencing of our own voices, and of oppressive distortions about our lives in the mainstream media have all made collecting and preserving our historical records an act of liberation.

The first LGBT community-based archival effort that I am aware of was the Lesbian Herstory Archives, founded in New York in 1974 by lesbian members of the Gay Academic Union. Forty-plus years later, it still exists, and it occupies its own building in Brooklyn, New York. The founders of the LHA made it their mission to spread the word about the importance of archiving for our community’s liberation, and in the 1970s and 1980s core members like Joan Nestle and Deborah Edel traveled widely giving public presentations meant to inspire and energize audiences. The impulse to create community history projects and archives spread over the next decades. It is not an easy thing to succeed at, since it requires a certain amount of technical knowledge and skill. It’s also not the kind of thing that is easily funded, since many funders just don’t “get” that history is a tool for fighting homophobia. Nevertheless, when the Lesbian and Gay Archives Roundtable (LAGAR) of the Society of American Archivists published a new edition of their Lavender Legacies Guide in 2012, they were able to locate by my count about twenty archives created and sustained by LGBT communities around the United States. And, the list of mainstream institutions that have developed LGBT collections, such as universities and state historical societies, is much, much longer. Places like Cornell University, the Schomburg Library in Harlem, the University of Minnesota, and the University of Southern California have made substantial commitments to developing LGBTQ archival collections.

To me, this is all very exciting and fills me with hope. In 1974, when I first began doing the research for what became Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities (1983), except for a short visit to the Institute for Sex Research (commonly known as The Kinsey Institute), none of my research was conducted “in the archives.” I visited the homes of activists, and worked my way through file cabinets and boxes that they kept in their studies, living rooms, basements, and garages. I visited the offices of homophile groups that still existed and explored their organizational records. In the case of the New York Mattachine Society, I was told one day that it would be closing at the end of the month, and I was welcome to take their office files if it would be useful to me! Needless to say, I responded affirmatively, and for the next several years two four-drawer file cabinets of Mattachine records filled one of the closets in my apartment. For a while, I didn’t have to travel far to be “in the archives.” But the experience serves as a reminder of how precarious the survival of our historical records has been.

While I am very pleased that there are more and more mainstream institutions that are committing themselves to preserving our history, I have a special affection for our community-based archives. They remain near and accessible to the community they are a part of and that they exist to serve. Creating and sustaining them are themselves acts of community building. And the materials that they house very much reflect that intimate connection to the local. Much of what is housed in these archives are not the records of the rich and the famous, the big headline-makers. Instead, LGBT archives tend to have the materials of local activists and community members, people whose work and lives may not have captured the attention of Fox News or The New York Times, but whose lives and actions make up the substance of the past. Many of the books that have been written on queer history over the last two decades might not have been possible without the existence of these community institutions and the stories contained in their many shelves of acid-free boxes.

The Gerber/Hart Library and Archives in Chicago is one of those community-based institutions. Founded in 1981, it came into being in part through the work of Gregory Sprague, a graduate student and activist who began doing research in the 1970s on queer Chicago history and who was part of the early national network of folks exploring LGBT history. While Gerber/Hart contains material from the Midwest generally, especially periodicals, the heart of its archival collection consists of the personal papers and organizational records generated in the greater Chicago area. Some collections are small, consisting of a single acid-free box; others are massive, spanning half a century and filling over a hundred boxes. The overwhelming majority of the collections contain materials from the 1960s forward, but there are a few that reach back into the earlier decades of the twentieth century.

Lately, I’ve been spending a couple of afternoons a week exploring some of these collections, trying to get a sense of the range of material and what it can reveal. Call me a history nerd, but there is something very exciting about finding a document that suddenly gives me a new understanding of where we’ve come from and how we’ve gotten here. For all the research and writing I have done, there is still much to be found that will make me smarter, make me grasp the world around me better, and help me think better about how to make change in the world.

Over the next months, I plan to share in occasional blog posts discoveries that I’ve stumbled upon in the Gerber/Hart archives. Its collections are rich, and making them more visible hopefully will spur more people to use them. Plus, I hope you’ll learn some new and surprising and fascinating things about our LGBT past. And, I also hope that folks from other community-based archives will do some blogging on OutHistory about their collections.

John D’Emilio is a Director of OutHistory.org and Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Illinois Chicago.