In the Archives

BY John D'Emilio ON October 19, 2016

“In the archives.” It’s a phrase that those of us who do history – whether as a profession or a passion or both – have used for a long time. It sometimes serves as shorthand to say that we’re doing research. But it is also often meant literally. “In the archives” is where we have gone to read the letters, diaries, memos, reports, and so many other documents from the past that are the raw material for writing histories of almost anything.

“In the archives.” It’s a phrase that those of us who do history – whether as a profession or a passion or both – have used for a long time. It sometimes serves as shorthand to say that we’re doing research. But it is also often meant literally. “In the archives” is where we have gone to read the letters, diaries, memos, reports, and so many other documents from the past that are the raw material for writing histories of almost anything.

Of course, in the era of the web, much archival material is relocating to hard drives and cloud servers. Many archives are digitizing at least some of their collections, and many individuals and organizations place the written documents they produce on websites as well. The result is that a day spent “in the archives” can now mean a day spent with one’s tablet, at a coffee shop, working one’s way through digitized records of the past.

Still, even with these revolutionary technological changes, the physical reality of archives as places that house the records of the past remains important. And this seems particularly true for the LGBTQ community. The generations of “wearing a mask” and having to pass as heterosexual, of invisibility and enforced silencing of our own voices, and of oppressive distortions about our lives in the mainstream media have all made collecting and preserving our historical records an act of liberation.

The first LGBT community-based archival effort that I am aware of was the Lesbian Herstory Archives, founded in New York in 1974 by lesbian members of the Gay Academic Union. Forty-plus years later, it still exists, and it occupies its own building in Brooklyn, New York. The founders of the LHA made it their mission to spread the word about the importance of archiving for our community’s liberation, and in the 1970s and 1980s core members like Joan Nestle and Deborah Edel traveled widely giving public presentations meant to inspire and energize audiences. The impulse to create community history projects and archives spread over the next decades. It is not an easy thing to succeed at, since it requires a certain amount of technical knowledge and skill. It’s also not the kind of thing that is easily funded, since many funders just don’t “get” that history is a tool for fighting homophobia. Nevertheless, when the Lesbian and Gay Archives Roundtable (LAGAR) of the Society of American Archivists published a new edition of their Lavender Legacies Guide in 2012, they were able to locate by my count about twenty archives created and sustained by LGBT communities around the United States. And, the list of mainstream institutions that have developed LGBT collections, such as universities and state historical societies, is much, much longer. Places like Cornell University, the Schomburg Library in Harlem, the University of Minnesota, and the University of Southern California have made substantial commitments to developing LGBTQ archival collections.

To me, this is all very exciting and fills me with hope. In 1974, when I first began doing the research for what became Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities (1983), except for a short visit to the Institute for Sex Research (commonly known as The Kinsey Institute), none of my research was conducted “in the archives.” I visited the homes of activists, and worked my way through file cabinets and boxes that they kept in their studies, living rooms, basements, and garages. I visited the offices of homophile groups that still existed and explored their organizational records. In the case of the New York Mattachine Society, I was told one day that it would be closing at the end of the month, and I was welcome to take their office files if it would be useful to me! Needless to say, I responded affirmatively, and for the next several years two four-drawer file cabinets of Mattachine records filled one of the closets in my apartment. For a while, I didn’t have to travel far to be “in the archives.” But the experience serves as a reminder of how precarious the survival of our historical records has been.

While I am very pleased that there are more and more mainstream institutions that are committing themselves to preserving our history, I have a special affection for our community-based archives. They remain near and accessible to the community they are a part of and that they exist to serve. Creating and sustaining them are themselves acts of community building. And the materials that they house very much reflect that intimate connection to the local. Much of what is housed in these archives are not the records of the rich and the famous, the big headline-makers. Instead, LGBT archives tend to have the materials of local activists and community members, people whose work and lives may not have captured the attention of Fox News or The New York Times, but whose lives and actions make up the substance of the past. Many of the books that have been written on queer history over the last two decades might not have been possible without the existence of these community institutions and the stories contained in their many shelves of acid-free boxes.

The Gerber/Hart Library and Archives in Chicago is one of those community-based institutions. Founded in 1981, it came into being in part through the work of Gregory Sprague, a graduate student and activist who began doing research in the 1970s on queer Chicago history and who was part of the early national network of folks exploring LGBT history. While Gerber/Hart contains material from the Midwest generally, especially periodicals, the heart of its archival collection consists of the personal papers and organizational records generated in the greater Chicago area. Some collections are small, consisting of a single acid-free box; others are massive, spanning half a century and filling over a hundred boxes. The overwhelming majority of the collections contain materials from the 1960s forward, but there are a few that reach back into the earlier decades of the twentieth century.

Lately, I’ve been spending a couple of afternoons a week exploring some of these collections, trying to get a sense of the range of material and what it can reveal. Call me a history nerd, but there is something very exciting about finding a document that suddenly gives me a new understanding of where we’ve come from and how we’ve gotten here. For all the research and writing I have done, there is still much to be found that will make me smarter, make me grasp the world around me better, and help me think better about how to make change in the world.

Over the next months, I plan to share in occasional blog posts discoveries that I’ve stumbled upon in the Gerber/Hart archives. Its collections are rich, and making them more visible hopefully will spur more people to use them. Plus, I hope you’ll learn some new and surprising and fascinating things about our LGBT past. And, I also hope that folks from other community-based archives will do some blogging on OutHistory about their collections.

John D’Emilio is a Director of OutHistory.org and Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Illinois Chicago.

On Ferguson and Queer Amnesia

BY Dan Royles ON December 2, 2014

Like many Americans, I was sickened—but not shocked—by a Missouri grand jury’s failure to indict police officer Darren Wilson for the August 9th murder of Mike Brown. The miscarriage of justice in Ferguson triggered over 130 protests in 37 states the day after the grand jury’s announcement.

Like many Americans, I was sickened—but not shocked—by a Missouri grand jury’s failure to indict police officer Darren Wilson for the August 9th murder of Mike Brown. The miscarriage of justice in Ferguson triggered over 130 protests in 37 states the day after the grand jury’s announcement.

One of those cities was Philadelphia, where hundreds of protestors gathered at City Hall the evening of November 25th before marching up to Temple University at the intersection of Broad Street and Cecil B. Moore (formerly Columbia) Avenue. This was a significant destination, since the neighborhood was the site of a three-day riot just over fifty years ago, in August 1964. Then, anger over racist policing, economic inequality, and the slow pace of political change boiled over into a mass rebellion that ended in hundreds of arrests, two deaths, and millions of dollars in property damage.

Half a century later, much has changed, although the issues in Philadelphia remain largely the same. Last week, marchers carried signs decrying police violence against communities of color, of which Mike Brown’s murder is just one example. Using a portable loudspeaker, one mother described the pain of burying her son, a victim of police violence. Others connected the event to a broader set of local tensions. As the crowd milled beneath Morgan Hall, the 27-story dormitory opened a year ago by Temple University, march leaders railed against gentrification in the neighborhood. In recent years, Temple has worked to shed its commuter-school image with new construction and an increased police presence aimed at reassuring white suburban students (and their parents) that the campus is safe. At the same time, longtime residents of the predominantly black North Philadelphia neighborhood (like other citizens in New Brunswick, New York City and other communities slowly giving way to university expansion) feel squeezed out by the Temple’s expanding footprint and the rising rents that come along with it.

As in other cities, queer activists like myself joined the demonstration. Philadelphia has a long history of radical queer politics, including organizing by queer people of color, and a large contingent of queer folks a march that snaked its way for almost four miles down Broad Street, from Center City to North Philadelphia and back, chanting, “No justice, no peace, no racist police!” and, “Shut it down!”

But these historic, intersecting community commitments are not always reflected, or even acknowledged, in queer media. When I returned home from the march and browsed through my blog feed, I found a torrent of posts from prominent gay blogs like Towleroad and Joe. My. God. focused on federal rulings against same-sex marriage bans in Arkansas and Mississippi. No doubt these decisions, along with the tidal wave of gay marriage legalization over the past year, represent a measure of progress. But the jubilant posts about Arkansas and Mississippi contrasted sharply with the anger and urgency of the march, captured in the widespread protest hashtag #blacklivesmatter. (To their credit, Joe. My. God. also covered the press conference and events unfolding in Ferguson; Towleroad, much less.) The degree to which gay marriage has moved into the political mainstream just over the past few years has been truly striking. Many, including John d’Emilio writing for this blog, have questioned whether this assimilationist agenda has supplanted the more radical challenges to American seen in gay liberation and ACT UP.

Like the community surrounding Temple University, gay politics has been gentrified. In urban neighborhoods undergoing redevelopment, white gay men and lesbians are often gentrifiers, being courted by developers for because we boost property values. But the costs and benefits of gentrification are not shared equally among queer people. According to Christina Hanhardt, LGBT calls for protection from street violence have historically resulted in increasing privatization and police surveillance of gay urban space, so-called “safety measures” that occur at the expense of poor and minority queer people.

As historically gay neighborhoods, such as New York’s Christopher Street or Philadelphia’s Gayborhood, become increasingly gentrified, they become whiter, richer and even straighter. They also become the sites of increased police violence. The increased police presence means that transgender women and queer youth, and particularly people of color in both groups, find themselves increasingly targeted for police harassment and arrest. Transgender people, and transgender people of color in particular, face vastly disproportionate rates of police violence. A 2012 report by the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs found that transgender people of color were almost two and a half times as likely to face police violence as white non-transgender people, even when they themselves were reporting violence. Transgender women also report being targeted by law enforcement, who use condom possession as evidence them on prostitution charges. Furthermore, queer youth make up 40% of the nation’s homeless youth, which in turn leads many to incarceration.

Along with the gentrification of gay urban spaces, mainstream gay politics has experienced what scholar-activist Sarah Schulman calls “gentrification of the mind”—a collective forgetting of the hard-won, sometimes radical, struggle for rights and recognition pursued by earlier generations of queers. White, affluent gay men and lesbians have attained increased respectability and cultural capital, and may very well see the issues of police brutality and judicial prejudice coming to the fore in Ferguson as disconnected from their own lives.

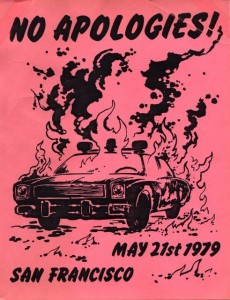

But it was not so long ago that gay people of all colors were targeted by police, who set up stings in popular cruising spots and raided gay bars and private parties, notably during the “lavender scare” that gripped Washington, DC during the 1950s and 1960s. It was the violent, rebellious response to such policing at New York’s Stonewall Inn, led by queers of color, that marked a turning point in the modern gay rights movement. And when San Francisco supervisor Dan White was convicted of manslaughter rather than murder in the killing of gay politician Harvey Milk in 1978, the city’s Castro District erupted in rebellion. In the face of such a gross miscarriage of justice, white gay rioters clashed with local police and causing hundreds of thousands of dollars in property damage. After the riots, the group Lesbians Against Police Violence created a poster featuring an illustration of a burning police car with “NO APOLOGIES!” in bold text. One imagines that today Castro residents might tweet pictures of the smoke and destruction, tagged #gaylivesmatter.

Even more recently, during the first decade of the AIDS crisis, gay lives of all colors were still viewed as expendable. In the early 1980s, Ronald Reagan’s press secretary Larry Speakes and the White House press corps openly laughed about the growing AIDS epidemic. Reagan himself famously did not publicly comment on AIDS until 1987. By the end of that year, over forty thousand Americans had died of the disease. It took sustained direct action from AIDS activists, particularly ACT UP, to bring drug costs down and speed up the approvals process for new medications. ACT UP protests were non-violent by design, but they were not peaceful—instead, they were disruptive and angry. At times, the group’s unruly civil disobedience brought police repression, as when local police beat members of the Philadelphia chapter during a 1991 protest outside the Bellevue Hotel in Center City. But it was actions such as these that remade HIV into a chronic, manageable condition in the middle 1990s with the advent of protease inhibitors.

This rage is absent from contemporary gay politics, even as HIV and AIDS also continue to affect gay and bisexual men more than any other group. As with policing, here too people of color bear the brunt of the burden, despite roughly even rates of safer sex practices across racial lines. Black gay and bisexual men account for about one in four new HIV infections. According to the Black AIDS Institute’s 2012 report, “Back of the Line,” by age twenty-five a black gay man has a 25% chance of contracting HIV; by the time he reaches forty, that number goes up to 60%. But again, the policing that makes affluent gay neighborhoods “safe” targets young queers of color and considers the tools of HIV prevention—condoms—to be evidence of illegal activity.

It may be easy for LGBT people—particularly those who are white and affluent—to see themselves as removed from the events in Ferguson, or the larger issues of police violence and mass incarceration that have brought thousands out in protest since the grand jury’s decision. This distancing ignores the complicity of mainstream LGBT politics in these social ills, as claims on gay respectability have been premised on the marginalization of the poor, minorities, and trans people. Moreover, it erases our own history of being policed and offered up as expendable, along with our rebellious responses to injustice. As we accede to this amnesia as the price of mainstream acceptance, we not only forget our past—we become agents of oppression in the present.