In the Archives | GLAAD Chicago

BY John D'Emilio ON November 16, 2016

On more than a few occasions in the last three or four years, as I’ve read the New York Times or the Chicago Tribune in the morning, I have had the sensation that I was reading an LGBT community newspaper. The range and number of stories have sometimes been staggering. There have been stories on the fight for marriage equality, of course, but I was also encountering news about changes in federal policies, tech industry initiatives, sports figures coming out, arts and culture profiles, young people organizing in their schools, op-ed pieces, and much, much more. In addition to the quantity of material, the positive perspective embedded in the reporting has also been noteworthy. The underlying point of view in the coverage and reporting has been one that affirms and validates LGBT communities and our fight for acceptance and justice.

Needless to say, it was not always so. In the pre-Stonewall years, before the rise of a militant movement, more typical coverage about our community was the alternation between a deep silence – no mention or recognition at all – and lurid stories that emphasized crime, danger, and moral corruption. This didn’t all magically change after Stonewall and the rise of a gay liberation movement. Part of what contributed to the rapid spread of AIDS in the 1980s was the tendency of the media either to ignore the story, thus perpetuating ignorance and an inability to act effectively against its spread, or to sensationalize the epidemic and thus perpetuate the deep cultural and institutional bias against men who have sex with men.

I received a powerful reminder of how slow the media was to change when I explored the GLAAD-Chicago collection at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives. The seven boxes of material, which span the first half of the 1990s, were donated by Randy Snyder, who served as the chapter’s executive director. GLAAD, which stands for Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, was a media watchdog organization formed in New York City in 1985 by Vito Russo and Darrell Yates Rist, both writers, as well as others. They acted in response to some of the horrifying coverage of AIDS coming from papers like the New York Post, owned by Rupert Murdoch. By the early 1990s, GLAAD had spawned perhaps a dozen local chapters, of which Chicago was one.

One of the major emphases in the work of GLAAD was its monitoring of the newly powerful “Religious Right.” For those interested in learning about and exploring the Religious Right more deeply in these years, the collection is a rich source of material. GLAAD kept track of and collected publications produced by organizations like the Traditional Values Coalition, the Family Research Institute, Focus on the Family and, locally, the Illinois Family Institute that, even today in 2016, is out there rousing opposition to initiatives to protect the safety and well being of transgender youth. The work of Paul Cameron especially drew GLAAD’s attention. A psychologist who was expelled from the American Psychological Association in 1983, Cameron produced reports with titles like “Criminality, Social Disruption, and Homosexuality”; “Child Molestation and Homosexuality”; and “Murder, Violence, and Homosexuality.” The GLAAD-Chicago papers also provide insight into the organizing being done to contain and discredit the Religious Right. Materials produced in the 1990s by organizations like the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and People for the American Way can be found here.

Interestingly, the work of a media watchdog group like GLAAD in these years was not confined to exposing extremists. Mainstream media outlets, including those that might be defined as liberal, needed to be targeted as well. A case in point was the Chicago Sun-Times, the city’s liberal daily paper. In the space of two months in 1994, the paper published two editorials that, shockingly, sounded as if the editorial board had lifted passages out of a Religious Right report. In response to the suburb of Oak Park extending medical benefits to the same-sex partners of town employees, the Sun-Times editorialized about “the importance of more traditional families” and “the central role in society traditional families must still assume.” Then, in an editorial coinciding with the 25th anniversary celebrations of the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969, the Sun-Times declared: “we oppose extending favored status to gays . . . the heterosexual majority is justifiably concerned that its values not be marginalized . . . and that a new set of rights not be extended to a privileged class.” GLAAD’s response was uncensored: “you have bought into the Religious Right’s lies and myths,” it wrote to the editorial page editor. Your claims, it said, were “vague and fallacious.”

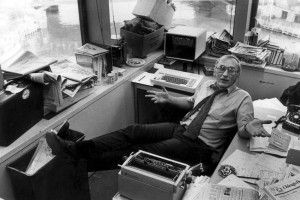

As with so many collections, there are also the jaw-dropping surprises. The GLAAD-Chicago papers include a “Mike Royko” folder. The Pulitzer Prize winning columnist was a fixture of Chicago journalism for decades. He had a take-no-prisoners style of writing that called out politicians and other public figures. His biography of Mayor Daley, Boss, was a best seller. In the folder is an unsigned typed memo, dated May 22, 1995, and with it a copy of a police report, dated December 17, 1994, documenting Royko’s arrest on DUI and resisting arrest charges in conjunction with a car crash. The memo called attention to comments of Royko’s documented in the report. Among other things, he screamed at the responding officer “you cocksucker” and “get your hands off me, you fucking fag.” Later he yelled, “Get away from me. What are you, fags?” and “Jag off, queer,” and finally, “What’s your ethnicity, you fag?” Because of Royko’s stature, the memo and report, which was sent to several LGBT organizations, created a media moment in Chicago

All this and more are to be found in the collection. GLAAD’s work helps explain why the tone and content of media coverage of LGBT issues is different today than it was even two decades ago. It didn’t happen by magic, by some mysterious process of evolution that brings progress. It took activist commitment and energy, and some of that commitment and energy are documented in the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.