In the Archives | Go Out and Interview Someone! The Robinn Dupree Papers

BY John D'Emilio ON November 30, 2016

Our life stories are the core content of LGBT history. Yes, our organizations and businesses produce records that detail important work. And mainstream institutions and social structures affect us deeply. But the texture and the challenges of what it means to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender at different times and in different places will only fully emerge if we make an effort to collect a broad range of our life stories. Reading – or hearing – the life story of an individual is not only compelling and absorbing in its own right. It can also open doors of understanding and offer revealing insights into what it was like to be . . . well, whatever combination of identities the individual brings to the interview. Each of our life stories will have something to tell us beyond the L,G,B, or T. We are also the products of regional culture, of racial and ethnic identity, of religious upbringing, of our particular family life, of class background, of work environments, and other matters as well.

The truth of this was brought home to me when I stumbled upon the small box of papers at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives labeled “Robinn Dupree.” In November 1996, a professor in folk studies at Western Kentucky University took his class of graduate students to Nashville to see a performance of female impersonators at a bar, The Connection. One of those students, Erin Roth, was so impressed by the event and by the lead performer, Robinn Dupree, that she asked for permission not to do her seminar paper on the assigned project – interviews/studies of “riverboat captains and old-time musicians” – but instead be allowed to interview Dupree and write about the art of female impersonation. The professor said yes, and so Roth conducted two interviews with Dupree, in March and April 1997. Fortunately for everyone else, she donated the tapes, a typed transcript, and her seminar paper to Gerber/Hart, so that Dupree’s account of her life is now available for study and inclusion in our collective history.

To summarize her story briefly: Dupree was born in 1952 in Chicago, her mother of Sicilian background and her father a Puerto Rican of African heritage. When she was in the 8th grade, she told her mother she was gay. As a teenager, she discovered the Baton Show Lounge, run by Jim Flint and already well-known for its performances by female impersonators. Soon she was sneaking out of the house to go there regularly. “It’s like I found what I wanted to do,” she told Roth, and soon Flint was coaching her and she began performing regularly.

Dupree performed at the Baton for almost a decade, and then moved on to another club, La Cage. In 1982, her boyfriend of ten years, who had connections to the Mafia, was killed in a car bombing outside their apartment building. Dupree realized it would be best to leave Chicago quickly, and she resettled in Louisville, Kentucky, where she rapidly made her way into the local female impersonator scene. Over the next decades, she performed for long stretches in Louisville, Nashville, and Indianapolis. According to online sources, her last show before retiring as a performer was just a few months ago, on February 13, 2016.

Reading the transcript of the interviews as well as Roth’s paper, I was struck by certain themes, some of which likely have broad applicability and some of which might be particular to Dupree. One involves economics. For those like Dupree who take the work of impersonation seriously as an art form and devote themselves to it, the economic realities can be harsh. On one hand, costs are high: the dresses, the jewelry, and everything else associated with the glamor of their performance are expensive, and new apparel has to be bought regularly for new shows. On the other hand, wages are low. Performers depend on tips, but these are unpredictable and often will not support them sufficiently. Thus, most impersonators need to have a day job, but that brings them up against the gender boundaries of the culture.

Another theme is family. As Dupree became a well-known, successful, and seasoned performer, younger impersonators-to-be came to her for advice, tutoring, and support, just as she had received from Jim Flint when she was starting and barely out of her teens. To many, she was their “mother,” and to Dupree, they were her “daughters.” The terms conjure up images of a warm and intimate family of choice, which it is. But behind the pull to use those terms is a harsh reality. After Dupree started performing, her biological mother broke off contact with her, and they remained separated for ten years. “Most people who do drag or want to become women, their family totally disowns them,” Dupree told Roth in their interview. Although Dupree acknowledged that much had changed in the 25-plus years since she had started performing, the loss of connection to families of origin remains true for many. Thus the relationships that were established had significant emotional and practical meaning. Dupree’s daughters often lived with her for long stretches as they worked to establish a life for themselves. Yes, it was a chosen family, but it was also a deeply needed family.

A third issue emerged in reading the interview with Dupree: the complexities and shadings of identity. At the time of the interview, in 1997, transgender had just recently established itself as a term of preference in the LGBT movement and in activist circles. Dupree described herself as “a pre-operative transsexual . . . I live every day of my life as a woman.” She had had surgeries done on her face to accentuate a kind of feminine beauty. She had also done hormone treatments in order to increase her believability as a performer in the world of female impersonation. “That’s why I actually ended up taking hormones and becoming a pre-op,” she told Roth. “Not to become a woman, but to look as much like a woman on stage as possible.” And within this world of stage performance, at least in the decades in which Dupree was an important presence, a range of self-understandings existed. “I have some daughters who want to be just entertainers. Then I have other daughters who want to go all the way through and become a woman.”

The Dupree oral history at Gerber/Hart is a treasure. We need more of them. Go out and interview someone – now!

In the Archives | The Melissa Ann Merry Papers

BY John D'Emilio ON October 31, 2016

One of the pleasant surprises that comes from snooping through the collections at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives is seeing how rich with information even small collections can be. The papers of Melissa Ann Merry are a perfect illustration of that.

One of the pleasant surprises that comes from snooping through the collections at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives is seeing how rich with information even small collections can be. The papers of Melissa Ann Merry are a perfect illustration of that.

Merry was a Chicago-based bisexual activist and performer. Born in Canton, Ohio, in 1963, she went to college at Eastern Michigan University and then moved to Chicago soon after graduating in 1986. It was in Chicago that she came out as bisexual, and she soon plunged into a world of bisexual activism that was coming together in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Locally, she got involved in the Bisexual Political Action Coalition (BIPAC) and was also a Midwest representative to the national organization BiNet (Bisexual Network of the USA), which grew out of the first national bisexual conference, held in San Francisco in June 1990. The papers she donated to Gerber/Hart consist of three boxes of material, almost all from between 1990 and 1995.

The first thing that emerged very clearly from surveying Merry’s papers is how important both the 1993 March on Washington and the 1994 Stonewall ’25 commemoration in NYC proved to be for bisexual activism and mobilization. Merry has several folders of material on each of them. First there was the organizing that needed to happen in order to have “Bi” be included in the official name of the 1993 March. Once that was achieved, planning for the March provided a great spur to local organizing across the U.S. to make sure that bisexuals participated in and were targeted by the efforts to guarantee a vast turnout in Washington in April 1993. Thus, the March proved to be not a single event, but a tool that had consequences afterward in the heightened level of local organization that it produced. The same can be said of the buildup for and aftermath of Stonewall ’25, which brought massive numbers of people to New York and achieved extraordinary media visibility. Not only did more local organizing emerge from both of them, but they also led to higher levels of national networking.

The increasing breadth and depth of bisexual organizing also emerges from another feature of Melissa Ann Merry’s papers. The collection contains a substantial number of bisexual publications from the early to mid-1990s. Among them are Anything That Moves, from the San Francisco Bay Area; Bi-Lines, from Madison, Wisconsin; Bi-Monthly from Champaign-Urbana, Illinois; the Boston Bisexual Women’s Network Newsletter; North Bi Northwest, out of Seattle; Bi-Atlanta; Bi-Centrist, from Washington, DC; Bi-Lines, from Chicago; and Bi-Focus from Philadelphia.

The increasing breadth and depth of bisexual organizing also emerges from another feature of Melissa Ann Merry’s papers. The collection contains a substantial number of bisexual publications from the early to mid-1990s. Among them are Anything That Moves, from the San Francisco Bay Area; Bi-Lines, from Madison, Wisconsin; Bi-Monthly from Champaign-Urbana, Illinois; the Boston Bisexual Women’s Network Newsletter; North Bi Northwest, out of Seattle; Bi-Atlanta; Bi-Centrist, from Washington, DC; Bi-Lines, from Chicago; and Bi-Focus from Philadelphia.

These newsletters and community magazines suggest that bisexuals were organizing on a far more extensive scale than is commonly recognized. In rare instances, an individual might prove capable of writing, producing, and distributing such a publication. But, typically, it requires a group to do the work of gathering the information, writing it up, and building an audience to read the material and sustain the newsletter or magazine. The existence of publications like these also suggests that there were sufficient groups and issues and campaigns to write about, thereby confirming that this was a period of intense and productive bisexual activism.

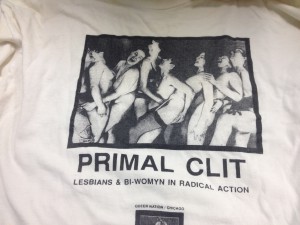

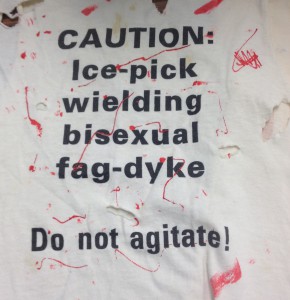

Finally, working my way through these three boxes of Merry’s papers also brought many smiles to my face. Besides documents, her collection also includes physical objects – tee-shirts, buttons, and political stickers. Many of them display a sense of humor that will easily produce chortles of laughter for the knowing but may also perhaps produce a moment of shock that successfully grabs the attention of those who may never have thought of bisexuality before. To mention just a few: there is a tee-shirt that read “Caution: Ice-pick wielding bisexual fag-dyke. Do not agitate!” Another portrays a line of women, some back-to-back and others face-to-face, with looks of ecstasy on their faces and the words “Primal Clit: Lesbians and Bi-Womyn in Radical Action.” There were stickers, meant to be placed on poles and walls and cars, one of which read “Bisexuals Don’t Sit on Fences. We Build Bridges!!!” And, finally, many buttons, among them the following: “I’m Bisexual – You’re Confused”; “Bi-Sexuals Are Equal Opportunity Lovers”; and “Two Roads Diverged in a Yellow Wood . . . and I Took Both.”

Finally, working my way through these three boxes of Merry’s papers also brought many smiles to my face. Besides documents, her collection also includes physical objects – tee-shirts, buttons, and political stickers. Many of them display a sense of humor that will easily produce chortles of laughter for the knowing but may also perhaps produce a moment of shock that successfully grabs the attention of those who may never have thought of bisexuality before. To mention just a few: there is a tee-shirt that read “Caution: Ice-pick wielding bisexual fag-dyke. Do not agitate!” Another portrays a line of women, some back-to-back and others face-to-face, with looks of ecstasy on their faces and the words “Primal Clit: Lesbians and Bi-Womyn in Radical Action.” There were stickers, meant to be placed on poles and walls and cars, one of which read “Bisexuals Don’t Sit on Fences. We Build Bridges!!!” And, finally, many buttons, among them the following: “I’m Bisexual – You’re Confused”; “Bi-Sexuals Are Equal Opportunity Lovers”; and “Two Roads Diverged in a Yellow Wood . . . and I Took Both.”

As I said at the beginning of this post, the Melissa Ann Merry Papers might be seen as a relatively small collection of three boxes, but they are packed with material that, cumulatively, provides rich insight into key years of bisexual activism in the United States.

In the Archives

BY John D'Emilio ON October 19, 2016

“In the archives.” It’s a phrase that those of us who do history – whether as a profession or a passion or both – have used for a long time. It sometimes serves as shorthand to say that we’re doing research. But it is also often meant literally. “In the archives” is where we have gone to read the letters, diaries, memos, reports, and so many other documents from the past that are the raw material for writing histories of almost anything.

“In the archives.” It’s a phrase that those of us who do history – whether as a profession or a passion or both – have used for a long time. It sometimes serves as shorthand to say that we’re doing research. But it is also often meant literally. “In the archives” is where we have gone to read the letters, diaries, memos, reports, and so many other documents from the past that are the raw material for writing histories of almost anything.

Of course, in the era of the web, much archival material is relocating to hard drives and cloud servers. Many archives are digitizing at least some of their collections, and many individuals and organizations place the written documents they produce on websites as well. The result is that a day spent “in the archives” can now mean a day spent with one’s tablet, at a coffee shop, working one’s way through digitized records of the past.

Still, even with these revolutionary technological changes, the physical reality of archives as places that house the records of the past remains important. And this seems particularly true for the LGBTQ community. The generations of “wearing a mask” and having to pass as heterosexual, of invisibility and enforced silencing of our own voices, and of oppressive distortions about our lives in the mainstream media have all made collecting and preserving our historical records an act of liberation.

The first LGBT community-based archival effort that I am aware of was the Lesbian Herstory Archives, founded in New York in 1974 by lesbian members of the Gay Academic Union. Forty-plus years later, it still exists, and it occupies its own building in Brooklyn, New York. The founders of the LHA made it their mission to spread the word about the importance of archiving for our community’s liberation, and in the 1970s and 1980s core members like Joan Nestle and Deborah Edel traveled widely giving public presentations meant to inspire and energize audiences. The impulse to create community history projects and archives spread over the next decades. It is not an easy thing to succeed at, since it requires a certain amount of technical knowledge and skill. It’s also not the kind of thing that is easily funded, since many funders just don’t “get” that history is a tool for fighting homophobia. Nevertheless, when the Lesbian and Gay Archives Roundtable (LAGAR) of the Society of American Archivists published a new edition of their Lavender Legacies Guide in 2012, they were able to locate by my count about twenty archives created and sustained by LGBT communities around the United States. And, the list of mainstream institutions that have developed LGBT collections, such as universities and state historical societies, is much, much longer. Places like Cornell University, the Schomburg Library in Harlem, the University of Minnesota, and the University of Southern California have made substantial commitments to developing LGBTQ archival collections.

To me, this is all very exciting and fills me with hope. In 1974, when I first began doing the research for what became Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities (1983), except for a short visit to the Institute for Sex Research (commonly known as The Kinsey Institute), none of my research was conducted “in the archives.” I visited the homes of activists, and worked my way through file cabinets and boxes that they kept in their studies, living rooms, basements, and garages. I visited the offices of homophile groups that still existed and explored their organizational records. In the case of the New York Mattachine Society, I was told one day that it would be closing at the end of the month, and I was welcome to take their office files if it would be useful to me! Needless to say, I responded affirmatively, and for the next several years two four-drawer file cabinets of Mattachine records filled one of the closets in my apartment. For a while, I didn’t have to travel far to be “in the archives.” But the experience serves as a reminder of how precarious the survival of our historical records has been.

While I am very pleased that there are more and more mainstream institutions that are committing themselves to preserving our history, I have a special affection for our community-based archives. They remain near and accessible to the community they are a part of and that they exist to serve. Creating and sustaining them are themselves acts of community building. And the materials that they house very much reflect that intimate connection to the local. Much of what is housed in these archives are not the records of the rich and the famous, the big headline-makers. Instead, LGBT archives tend to have the materials of local activists and community members, people whose work and lives may not have captured the attention of Fox News or The New York Times, but whose lives and actions make up the substance of the past. Many of the books that have been written on queer history over the last two decades might not have been possible without the existence of these community institutions and the stories contained in their many shelves of acid-free boxes.

The Gerber/Hart Library and Archives in Chicago is one of those community-based institutions. Founded in 1981, it came into being in part through the work of Gregory Sprague, a graduate student and activist who began doing research in the 1970s on queer Chicago history and who was part of the early national network of folks exploring LGBT history. While Gerber/Hart contains material from the Midwest generally, especially periodicals, the heart of its archival collection consists of the personal papers and organizational records generated in the greater Chicago area. Some collections are small, consisting of a single acid-free box; others are massive, spanning half a century and filling over a hundred boxes. The overwhelming majority of the collections contain materials from the 1960s forward, but there are a few that reach back into the earlier decades of the twentieth century.

Lately, I’ve been spending a couple of afternoons a week exploring some of these collections, trying to get a sense of the range of material and what it can reveal. Call me a history nerd, but there is something very exciting about finding a document that suddenly gives me a new understanding of where we’ve come from and how we’ve gotten here. For all the research and writing I have done, there is still much to be found that will make me smarter, make me grasp the world around me better, and help me think better about how to make change in the world.

Over the next months, I plan to share in occasional blog posts discoveries that I’ve stumbled upon in the Gerber/Hart archives. Its collections are rich, and making them more visible hopefully will spur more people to use them. Plus, I hope you’ll learn some new and surprising and fascinating things about our LGBT past. And, I also hope that folks from other community-based archives will do some blogging on OutHistory about their collections.

John D’Emilio is a Director of OutHistory.org and Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Illinois Chicago.

Sexy Darwin

BY Claire Potter ON October 12, 2014

I want to start this post, which is really about science and it’s various discontents, by saying: The Nation, a publication to which I am extremely loyal, does not publish enough in its regular edition, or even its blogs about LGBT people. Perhaps this has something to do with the fact that it is no longer fashionable on the left, especially among radical queers, to push publications like The Nation to take LGBT people’s politics,or their lives, seriously. Despite the fact that millions of queers are homeless, poor, racially and sexually discriminated against, there appears to be a general consensus that in the hierarchy of global and national suffering, we simply do not rank.

I want to start this post, which is really about science and it’s various discontents, by saying: The Nation, a publication to which I am extremely loyal, does not publish enough in its regular edition, or even its blogs about LGBT people. Perhaps this has something to do with the fact that it is no longer fashionable on the left, especially among radical queers, to push publications like The Nation to take LGBT people’s politics,or their lives, seriously. Despite the fact that millions of queers are homeless, poor, racially and sexually discriminated against, there appears to be a general consensus that in the hierarchy of global and national suffering, we simply do not rank.

But you do have to credit The Nation with publishing more about sex in the last few years. JoAnn Wypijewski is doing a great job with the Carnal Knowledge feature, and no longer a backup to Katha Pollitt. Pollitt has been fighting the right (and the occasional fellow columnist, when they still let them do that at The Nation) on sex and gender for decades. Michelle Goldberg is a new utility infielder on the feminism beat. Richard Kim occasionally answers the call on queer issues but he’s been kicked upstairs to editorial. Despite these talented folks, we rarely see a feature or a cover story about LGBT people, or even the politics of sex, absent a compelling policy controversy (for example, Republican politicians pointing out a woman’s miraculous ability to not conceive if she just puts her mind on it.)

So when I stumbled upon an unread issue from earlier this fall that featured “Survival of the Sexiest: How Evolutionary Psychology Went Viral,” by Mal Ahern and Moira Weigal (September 9 2014) I had to wish queer people into it. Ahern and Weigal describe how evolutionary psychology (EP), a field with questionable methods and even more questionable conclusions has re-emerged as a respectable way of drawing conclusions about human sexual behavior. Heterosexual human behavior, that is.

In a nutshell, EP is a neo-Darwinian theory. It proposes that we are all hardwired to propagate the human species successfully: every sexual decision we make, and urge we feel, is linked to that. “We” are, of course, heterosexual in these studies. Our courting behaviors, attractions and sexual choices are all geared towards producing hardy offspring that carry our genetic material into infinity. Depending on our gender, we do this either by gaining access to young wombs or acquiring sperm from seemingly hardy, aggressive, successful males.

EPmakes me think of a middle school girls’ school joke in which, as a group, we would thrust our adolescent chests forward while chanting:

We must, we must,

We must increase the bust.

The bigger, the better,

The tighter the sweater, the more the boys depend on us.

To feed. The babies. We must….

(Etc. Repeat until falling down laughing or begged to stop.)

The popularity of EP as an explanation for otherwise inexplicable heterosexual behavior (for example, a guy having sex with a woman he meets at a bar who he then never calls again) is also a reminder that robustly funded and seemingly respectable scientific research continues to promote the idea that LGBT people are biologically broken or deviant. Because these are stupid overdetermined theories, EP’s explanations for human sexual behavior were dismissed as recently as the 1980s. But now they are back.

So what accounts for EP’s resurgence in science and popular culture in the 21st century? “In order to understand why there is such an insatiable appetite for this kind of explanation,” Ahern and Weigel argue,

why even the readers of center-left publications like The New York Times are willing to accept the idea that gender roles and relations are hardwired—we need to investigate how evolutionary psychology itself evolved. We propose that its popular success has nothing to do with how plausibly its proponents describe the struggle to survive on the plains of the Pleistocene Era. What it does reflect is the brutally competitive economic environment today. Evolutionary psychology may just provide an ideal theory of love for the precarious age in which we live.

Here’s the other thing about this field, which is hardwired into the larger field of sociobiology: like William Masters and Virginia Johnson, the researchers who have done the most prominent work in the field are all heterosexual couples themselves, many married, or ex-married, to each other. “Given the preponderance of couples at the forefront, and their desire to win attention (and thus funding),” Ahern and Weigel write, “it may have been inevitable that the new discipline would be sex-crazed. Sex and gender differences became evolutionary psychology’s most important topics.

Does EP apply to LGBT people at all as a method for figuring out why we are attracted to each other, aside from targeting a partner who seems to have the physical characteristics necessary for curating our Judy Garland LPs? Well, it appears that these theories are themselves “naturally” selective, and are only relevant to pairings that are most obviously reproductive in nature, even though men and women often do not naturally reproduce. About 10% of women who have sex with (possibly handsome but uncertainly fertile) men require medical interventions to conceive and carry a child to term (I’m going out on a limb to say: double that number for professional women.) Gay and lesbian people don’t qualify as sexual subjects who come together over the possibility of immediate, closed circuit reproduction, although bisexual and trans people might, I suppose. However, helped along by mass culture, EP has proven itself to be a fit survivor all on its own, and I think we can be confident that the proliferation of inseminating, sperm-donating, cross adopting, surrogate-employing queers will soon provide new opportunities for a field whose only consistent interest seems to be shilling sexist stereotypes.